How one man was convicted of murder and allegedly killed again years later | Locked Inside, a 12 News podcast

Christopher Lambeth was arrested in April 2021 for the death of his housemate at a Gilbert group home, but there's more to uncover in this murder.

It’s a big mystery with police reports, crime scenes and mounting evidence.

But this isn’t your run-of-the-mill true-crime story.

Locked Inside, a new 12-News I-Team and VAULT Studios podcast, follows the harrowing and heartbreaking story of Christopher Lambeth and those who crossed his path along the way.

The podcast digs into a subject that doesn’t often get this type of careful in-depth attention in the mainstream: mental health and care for those who need help.

New episodes of Locked Inside drop every Tuesday on 12News.com, Youtube and your favorite podcast app.

Chapter 1 Murder at Tilda Manor

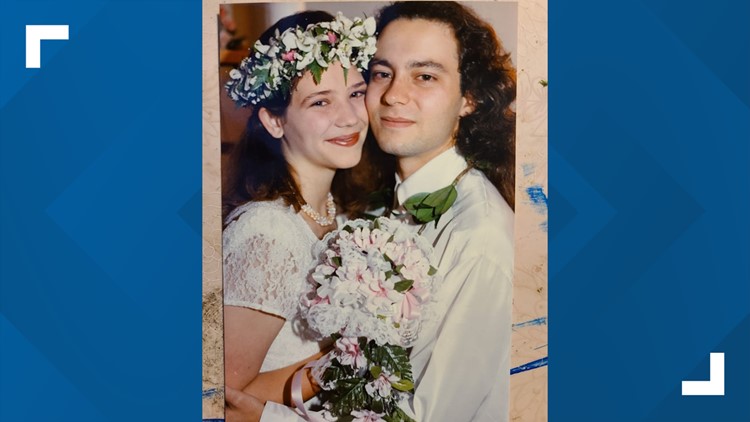

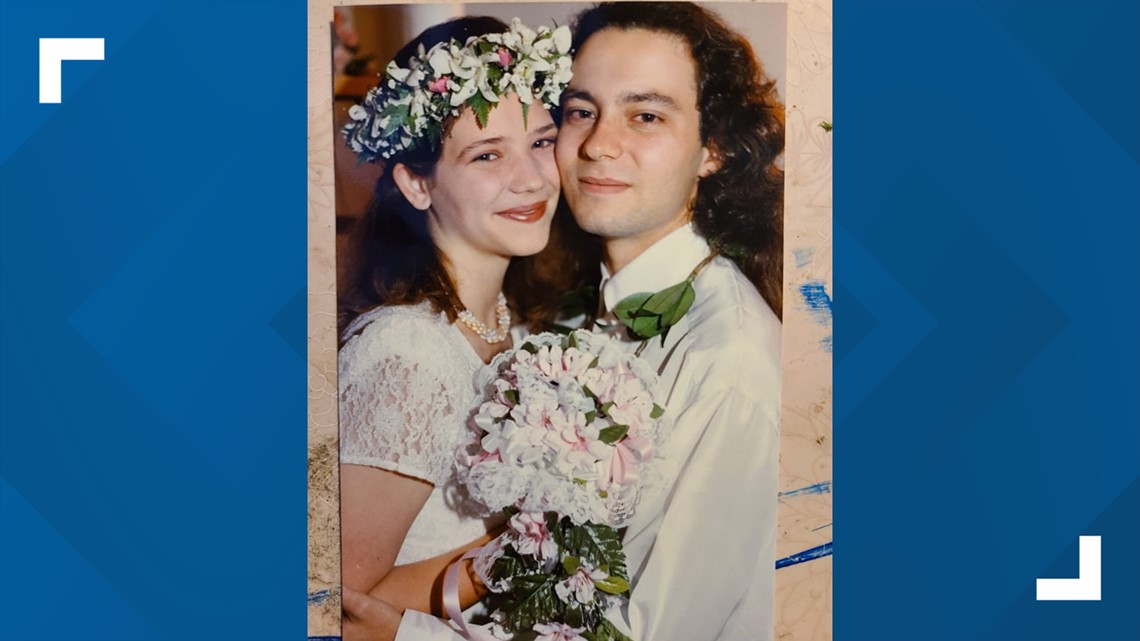

It all started on a bus. Guy sees girl. Girl flashes a smile. It’s a meet-cute you’d think only happened in the movies.

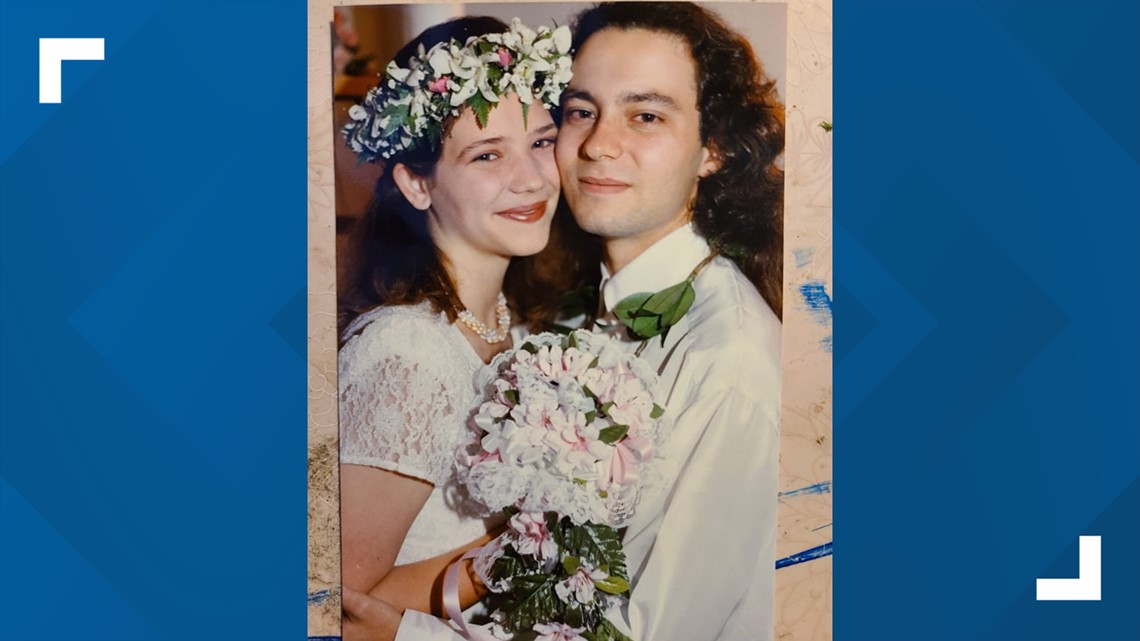

But that’s exactly how Nicole Williams met Steven Howells.

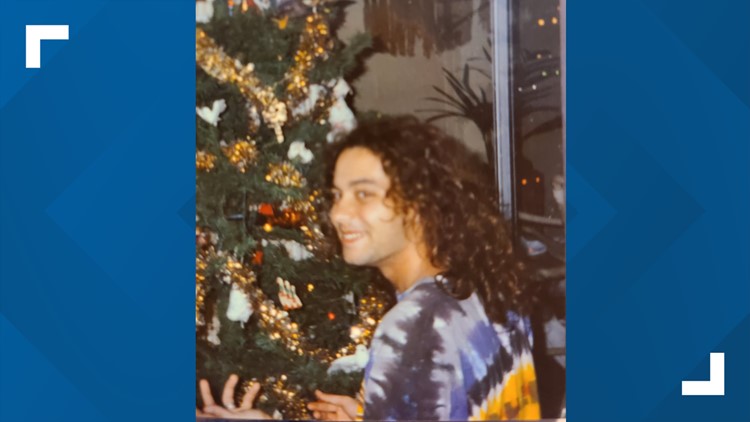

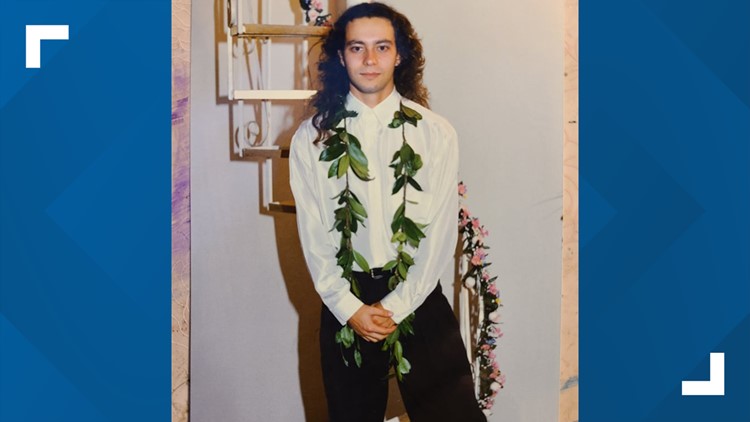

“We were both heading on the bus to the same place. And he had this gorgeous long, curly hair. And so I smiled and we started talking and started dating from there.”

This was 1993 in Hawaii, according to Nicole. A paradise for the young couple. Within five months of meeting, they married.

She was 17 and he would have been around 22 years old.

“I mean, we were young,” she said. “And so there was always a financial struggle, especially in Hawaii, where it's so expensive to live. But it was great.”

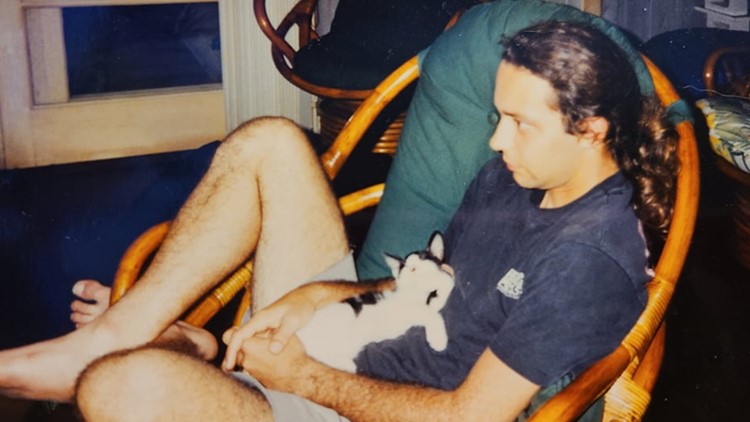

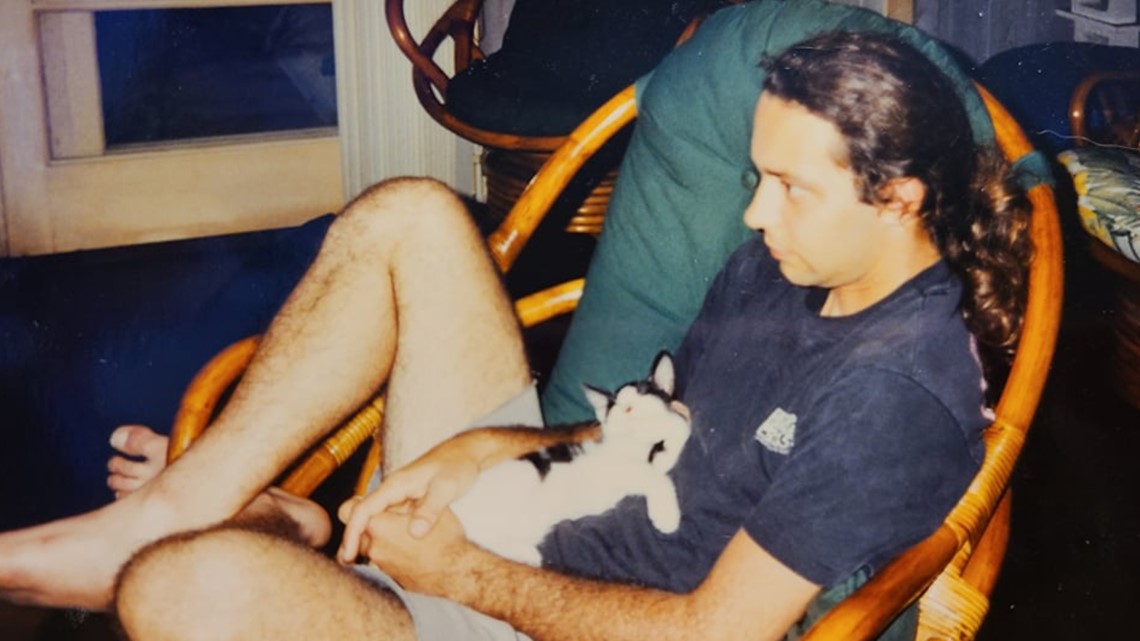

Nicole remembers Steven was very involved in the music business. She said he studied at the Art Institute of Seattle, played saxophone, and worked with bands. He and some friends would go to the beach and play improv jazz for hours.

“You know, he never had the goal of being the front man leading the act,” Nicole shared. “But he loved being behind the scenes and doing the music, mixing and recording and helping from the back end being able to put music out.”

About a year into their marriage, Nicole started noticing a shift.

“At first it was small things,” she remembered. “And he would make little comments that were just a little off. They started progressing more, we had a park that we would walk by. And he started talking to me about a frog he met there, and the conversations he was having with this frog. But it took me a little bit to realize that it wasn't just him talking, he was hearing the frog talk to him.”

She said he started experiencing delusions. And that they started affecting his work. She said she saw him get worse over time. And his aspirations of working in the music industry gradually devolved into just trying to get by day by day.

Despite trying, help was hard to come by.

“And he still had so many dreams and things that he wanted to do,” Nicole remembered. “And as the years went by the reality in himself was that those were probably not going to happen.”

She said his goals changed to keeping a job, living on his own.

“And so it has been really hard on that and watching him struggle,” Nicole said. “Struggle with medications and start getting a little better and then those wouldn’t work and kind of yo-yoing up and down in his mental health.”

Locked Inside: Steven Howells and the murder at Tilda Manor

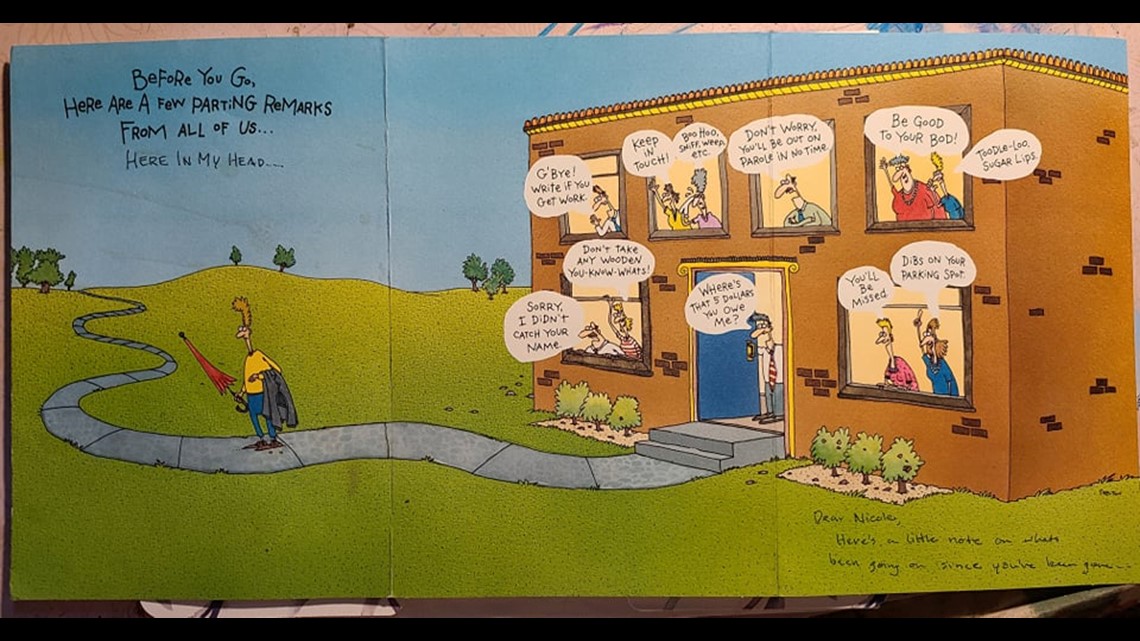

The yo-yoing became too much for both of them. They divorced in 1994. After the split, Nicole said she and Steven kept in touch, but it wasn’t easy. Steven would eventually move to Arizona where he had family. Nicole said he’d try staying in places like group homes with supported living, but it was hard to keep track of his every move.

“We talked on the phone when he was doing good,” she said. “When the meds would kind of stop working, he would disappear. And then if he got on something new and it would start working, he would call me. And eventually, he just felt that he was holding me back from living my life. So he stopped the connection.”

Even though Steven stopped reaching out, Nicole never stopped thinking about him. She’d even try to look for him whenever she went back to Hawaii to visit. Just to check in.

“I would check the Social Security death index once a year to see if he showed up,” she remembered. “I would walk through a lot of the homeless shelters, and things like that in case he was out on the street. Making sure he's OK. That was the main thing. We want to know he's OK.”

But Steven wasn’t OK.

'So, you guys left the house without any keys?'

The sun was just starting to rise on April 12, 2021, when two police officers pulled up to a quiet street in Gilbert, Ariz. They were dispatched to the scene after a frantic 911 call.

OPERATOR: Sir, we have a bad connection. Where are you at? 3583 East Wildhorse?

It’s the address for a group home called Tilda Manor. The home is licensed by the state as a behavioral health facility, meant to provide care and oversee treatment for people placed in the home.

Tilda Manor looks like most other homes on the street. It’s a two-story beige house with big windows. The blinds are typically drawn.

The facility is supposed to provide 24-hour supervision to its residents, people who need behavioral and mental health services, according to its state license.

On that morning in April, a group home staff member made a muffled call for help.

OPERATOR: I’m sorry I’m having a hard time understanding you. What did he do?

CALLER: I said one of our clients just attacked us.

OPERATOR: OK.

CALLER: It’s a group home.

The group home staff member dialed 911 after running outside the home with his coworker. He said one of the group home’s residents tried to attack them that morning.

OPERATOR: We have officers on the way. Does anybody need medical? Do you need the paramedics to come check on you?

CALLER: No, not yet. We’re outside waiting. Just the police.

OPERATOR: Just the police? OK. Where is your client now?

CALLER: He’s inside the house. We’re outside waiting.

But that employee was wrong. Someone did need medical help.

Audio of the Tilda Manor group home 911 call:

OPERATOR: How is he going to react to my officers? Is he going to be cooperative for my officers? Is he going to be hostile toward my officers?

CALLER: Actually, I don’t know because right now he’s kind of violent.

The two officers arrived armed with that information — that a potentially violent resident could be inside the home.

Body camera video from Gilbert Police Department shows they parked the car and walked up to the two group home employees standing in the street.

GPD Officer: What happened today?

Staff: He was naked and he attacked me.

GPD Officer: And how did he attack you?

These employees tried to explain that a resident inside the home tried to hurt them and that they ran outside. They said that resident was a man named Christopher Lambeth.

BODY CAM: Was he in his room when you guys left?

Staff: He’s in the house

GPD Officer: So, we’ll go and talk to him real quick.

The footage shows the two officers and two staff members walking toward the door. One of the officers tried to twist the doorknob.

GPD Officer: It’s locked. Do you guys have a key? It’s locked.

The officers learned the door was locked and neither employee had a key.

GPD Officer: How are you going to get back in? Do you normally go on the side of the house?

GPD Officer: Is there a spare key in the van anywhere?

Staff: No

GPD Officer: So, you guys left the house without any keys?

At this point, about six minutes after the officers arrived, body camera footage showed them standing at the locked door, pondering how to get inside. Then, one of the officers peered through the window to the left of the door. And what he saw changed everything.

GPD Officer: There’s a man inside bleeding from his head.

It was a man lying in a pool of blood on a bedroom floor. The officers called for back-up and their pace instantly changed. One of the officers started kicking the door while the other asked if the employees could hop the fence into the backyard and get in through a door in the back. One employee and one officer raced to the back gate while the other officer kept kicking the front door. Eventually one of the residents opened the door and the officers rushed inside, trying to get to the man bleeding on the floor.

One officer told the other that he had no pulse. They started what sounded like chest compressions in that body camera video. Then, one of the officers noticed something else.

GPD Officer: There’s something in the shower right now.

GPD Officer: Gotcha.

GPD Officer: Just watch your step, OK? There’s blood coming from the bedroom…

The trail of blood led to a closed door. It turned out to be the bathroom and the shower was running.

GPD Officer: You know what? Somebody probably walked up through this and went into the bathroom and took a shower. That’s what happened. So, whoever is in the shower is the one who actually walked through this.

The officers called for firefighters to come in and try to help the bleeding man. Then the bathroom door opened.

Parts of this audio and video were redacted by Gilbert Police, so it’s not clear what was said in these initial moments with the person in the bathroom. The audio and video that was not redacted shows the officers were talking with a man who just got out of the shower. He was getting dressed and told the officers his name was Christopher Lambeth.

The officers knew this was the man the group home employees called about. Once he was fully dressed, one of the officers turned him around and put him in handcuffs. The officer walked Lambeth through the halls and toward the front door as he explained to Lambeth that he had the right to remain silent. They stepped outside into a yard teeming with first responders and beelined toward a police car. The officer put Lambeth in the back.

By the time the firefighters got to the man lying in blood on the floor, it was too late. The chest compressions didn’t work.

Steven Howells was declared dead at 5:46 a.m.

'This should have never happened.'

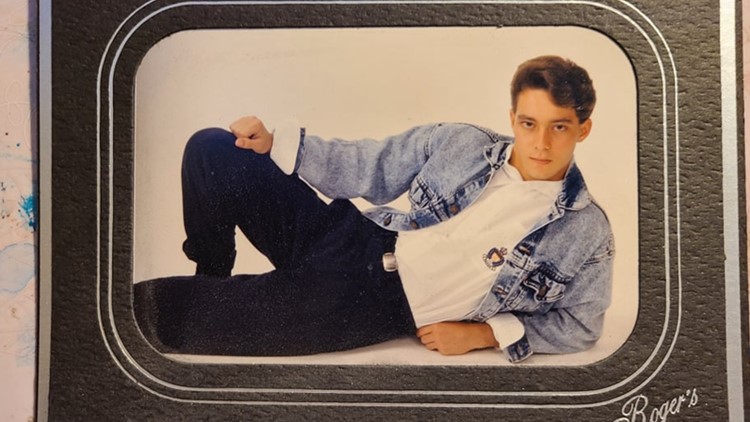

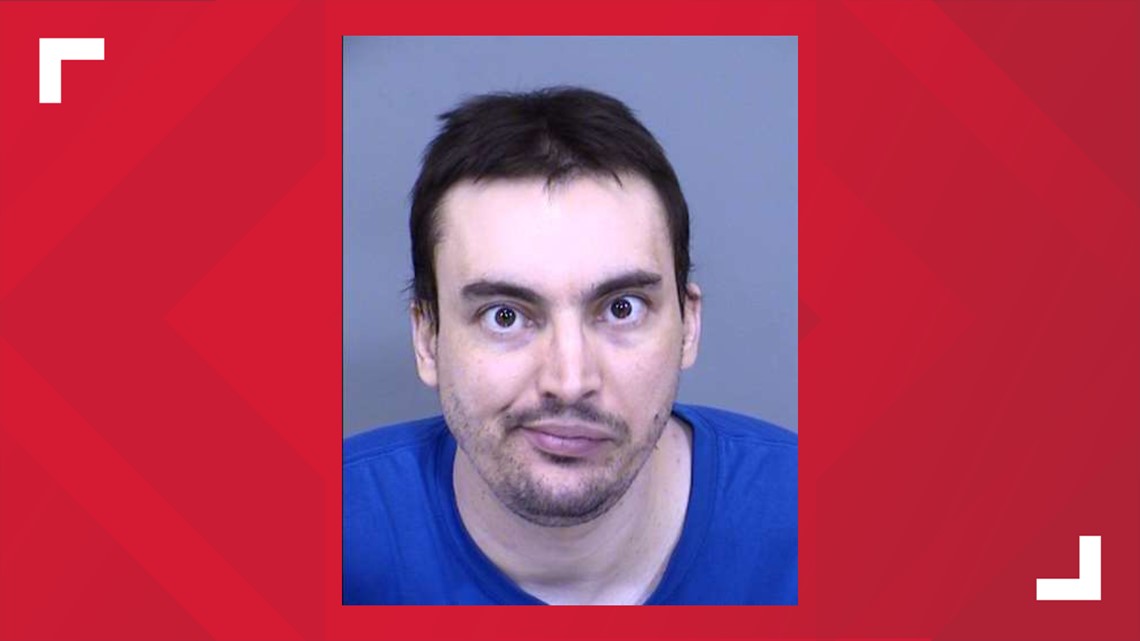

The first photo posted on Steven Howells’ online obituary seemed like it was taken years ago. It shows a young guy with dark eyes and brown hair, half-smiling at the camera. He was wearing a denim jacket with the collar popped.

The first few lines said Steven was born in Hawaii and moved to Arizona in 1998. He lived to be 49 years old.

The comments on the page appeared to be mostly from family or friends who knew him way back when, revealing glimpses of a man once full of life who’d been dealt a really hard hand.

His ex-wife Nicole shared some photos of her own and left a heartfelt message.

“He never deserved to end like this,” she wrote. “I am who and what I am today because of him.”

She ended with a heartbreaking, “I love you always.”

When Steven was killed, Nicole estimated it had been about 10 to 15 years since she last spoke with him.

In the years after their divorce, she got remarried and became a mom. She now lives in Colorado. Nicole wound up taking a trip to Seattle soon after she learned Steven was killed. She said it brought some closure, in a way, as Seattle was where he did his music studies. She started processing how Steven’s death could have happened.

“That should have never happened,” Nicole said. “I've worried about things like that happening, but I worried about it on the street. Not in someplace that's supposed to keep them safe."

No one at Tilda Manor ever commented on the killing or the events leading up to it.

However, a police report released by Gilbert police shed light on the events that morning.

Steven Howells was one of nine residents living at Tilda Manor, three women and six men. Christopher Lambeth had reportedly already been living there a few years when Steven Howells moved in. It’s not clear exactly when Steven went to live at Tilda Manor, but one of the staff members told police he had been living at the home about four months at the time he was killed.

Other housemates told police Steven Howells and Christopher Lambeth didn’t really know each other. Lambeth would usually keep to himself, in his own room, according to the police report. It also detailed that Steven originally had a roommate, but that person moved out, meaning Steven Howells had a room to himself, right by the front door. The same room where officers found him bleeding.

The night before he was killed, the two employees told police that they clocked in for their overnight shift. They told police it started out quietly. Everyone was in their rooms.

The employees told police they did bed-checks at 2 a.m. and noticed Christopher Lambeth was pacing around his room. By 4 a.m. they thought he went to sleep.

The police report details that around 5 a.m., one of those employees was prepping medications for the residents when he suddenly heard a fight. He ran toward the living room and saw his coworker struggling with Christopher Lambeth who wasn’t wearing any clothes. Lambeth apparently tried to punch the other employee in the face and both workers ran outside.

At first, the workers told police that Lambeth followed them to the driveway, but he ultimately went back inside and locked the door, locking the employees out. It’s not clear whether Steven was attacked before or after the employees got locked out.

“If anything, I could see him being the person who would stand up and try to calm somebody down or de-escalate him,” Nicole said of Steven Howells. “And although I don't know what happened in the room, that would be my bet of what happened.”

Christopher Lambeth admitted on the scene that he “killed him,” the police report stated. That he “bludgeoned” Steven Howells “to death.” He later told police he saw Steven go and use the bathroom and then he followed Steven back to his bedroom and started choking him. Lambeth said he didn’t know why he did this and no one else saw what happened.

After he was arrested, he appeared before a judge who said he was charged with second-degree murder in the death of Steven Howells. In video from that court proceeding, you can see Lambeth appear virtually from what appeared to be a jail cell. He was staring at the camera through his glasses, looking through a crack in the doorway. He didn’t say a word as the judge spoke to him.

The judge told him he would have a lawyer assigned to him and that he’d be held on a $2 million bond. He later submitted a plea of “not guilty.”

Instead of sitting in a jail cell charged with murder, the police report detailed that April 12, 2021 should have been moving day for Christopher Lambeth.

Tilda Manor staff told police he’d been living at the group home since 2018, although his move-in date is not part of the public record. Employees told police that in all his time at the home, they never had any problems with him. In fact, he was doing so well with his treatment at the home that he was set to move into his own apartment at 11 a.m. the morning of the killing.

One staff member told police that, “he could handle it.”

But in Lambeth’s life, April 12 stands out for another reason.

On April 12, 2005, exactly 16 years before the killing at the Tilda Manor group home, Christopher Lambeth was taken to a different jail as a suspect in a different deadly crime.

You can catch that story in the next chapter of Locked Inside: Guilty Except Insane starting April 19, 2022 wherever you listen to podcasts.

No one working with or representing Tilda Manor agreed to talk with 12 News at this point in our story.

Christopher Lambeth’s current attorney did not respond to any of our requests for comment at the time this episode was recorded.

Chapter 2 Guilty Except Insane

On April 12, 2005, Christopher Lambeth sat handcuffed at the Pima County Sheriff’s Department in Tucson. He was face-to-face with two detectives after he was taken into custody from a bloody home in Rillito. They start by asking his name and age. He told them who he was and that he was 20 years old.

Then the detectives braced themselves for what he was about to say next.

Rillito is a small, tight-knit community about a 20-minute drive north of downtown Tucson.

Just two days earlier, on April 10, 2005, something unsettling stood out. It was a Sunday morning and many people in Rillito were getting ready for church.

When services started that morning, some people noticed that two community fixtures, Carl and Patricia Gremmler, weren’t there.

The couple were grandparents, both in their 70s and well-known as activists in Rillito. Former Tucson Citizen reporter Sherly Kornman remembered they would protest emissions from a nearby cement factory.

“And they were very vocal, you know, I guess you call them activists,” Kornman said. “Gray haired activists who really cared about their community.”

Friends of the Gremmlers told Kornman that the couple volunteered at a local food bank.

“They were very socially-conscious,” Kornman said. “Wouldn’t hurt a fly kind of people.”

The Gremmlers' absence at church that Sunday morning wasn’t just noticeable, it was out of the norm. One of the couple’s friends tried calling for a few days after missing them at church and finally decided to go to their house and see what was up.

A murder scene: The home and town of Carl and Patricia Gremmler

This friend had known the Gremmlers for about a decade, according to an investigation report. He’d been to their home before. It sat right along I-10, the main highway connecting Tucson to Phoenix. The Gremmlers had their own house, a rental home, a garage and a red-brick business building all on the same plot of land. Carl Gremmler, a car enthusiast, ran an auto shop of sorts from that garage.

The Gremmlers’ friend told investigators that he noticed a broken window on one of the front buildings when he pulled up to their property. When he went through the gate, he noticed another broken window. He didn’t go inside any of the buildings. He called his wife, who then called the sheriff’s department.

When two deputies got there, they started by searching the red-brick business building, according to the investigation report. The whole place had been ransacked. Blinds ripped, widows busted out, furniture overturned and part of a computer thrown to the floor.

One deputy wrote in the report that the person who did this must have been “very angry.”

The deputies moved to the garage, filled with antique cars Carl had been working on. They didn’t notice anything out of place and made their way to the house. As they approached the sliding glass door at the back of the Gremmlers’ home, one deputy took out a pen and gingerly used it to pull the door open, in case there were any fingerprints or evidence on the handle. The moment they stepped inside they knew something was very wrong.

The investigation report detailed that all the lights were off. The front room was trashed. The widescreen TV was shattered in its case. The couples’ two dogs were inside. The deputies noted that it seemed like they hadn’t been out in a few days, based on the mess they left on the floor.

The deputies pushed forward through the destruction, guns drawn. They made their way to a bedroom door, where they realized someone was lying in the bed under the covers.

The deputies didn’t know it at the time, but this person was Christopher Lambeth. The deputies told him to get out of bed and lie down on his stomach in the hallway.

After putting Lambeth in handcuffs, records show Lambeth admitted he killed the people who lived in the home and directed the deputies to the other bedroom across the hall. One deputy wrote that the room was in “extreme disarray” and they could hardly step inside.

'These people were completely defenseless'

Former Tucson Citizen reporter Sheryl Kornman covered the crime scene at the Gremmlers’ home.

“All they could see was just a giant, bloody mess,” she remembered reporting, referring to the responding deputies.

The investigation report details that the first body they saw was Patricia’s, slumped on the bed against some pillows. Then they found Carl’s body on the floor. Investigators determined they’d been dead for a few days.

“And they were stabbed so many times,” Kornman said. “They never released the count. But they were so brutalized, that they had to have a closed casket for the funeral.”

Sheryl Kornman spent the days after this brutal discovery connecting with the Gremmlers’ friends and investigators.

“And the sheriff's department, the deputies were really upset about it,” she remembered. “Because, you know, seeing it was just horrific. Because these people were completely defenseless.”

Those who knew the Gremmlers the best were devastated, but not totally shocked.

“It gives me chills, again, at the brutality of the murder,” Kornman said. “Feeling like I feel now like I felt then. This didn't have to happen, these were vulnerable, older people who never should have been put in that position.”

Christopher Lambeth wasn’t an intruder in their house. Christopher Lambeth was Carl and Patricia Gremmler's grandson.

After the deputies found the Gremmlers brutally stabbed to death in their own home, they wrapped Lambeth in a blanket and walked him out to a squad car. The dogs in the house started to follow them as they walked outside and one deputy wrote that Lambeth simply said, “Please close the gate. The dogs will get out.”

Then, Christopher Lambeth was face to face with deputies, answering questions about what happened to his grandparents. The sheriff’s department originally recorded this interview but burned the tapes in a routine cleanout in January 2020.

The following printed interview is part of a transcript provided by the Pima County Sheriff’s Department in a 12 News records request.

Detective: Are they alive or dead right now?

Lambeth: They’re dead.

Detective: OK, how do you know they’re dead?

Lambeth: I killed ‘em.

Detective: You killed ‘em?

Lambeth: Yeah.

Records show Christopher Lambeth admitted several times that he killed his grandparents and that he was “happy that they’re dead now.” But he was hesitant to tell investigators why he killed them.

Detective: OK, I mean was there some kind of argument between you guys? How did this - how did this turn into them being dead?

Lambeth: Personal problems. I don’t want to talk about it.

Detective: Personal problems you have or between you and them?

Lambeth: Between us.

Detective: Between you and your grandparents?

Lambeth: Yes.

Detective: Does it go back a long way or something?

Lambeth: Yeah.

Detective: Like family history?

Lambeth: Yeah.

Read the full transcript here:

According to court records, Lambeth’s father died when he was young. Lambeth and his sister lived with their aunt and uncle for a while before moving back in with their mother, according to Kornman’s reporting. It seemed symptoms started around his teenage years. He was admitted to hospitals or other treatment facilities and court-ordered for psychiatric evaluations multiple times, according to court and investigation records.

He was eventually diagnosed with bipolar and schizoaffective disorder.

“So, he was diagnosed,” Kornman detailed. “But he was covered as what they call a ‘public pay’ individual because he was deemed disabled. Under the disability laws, he could get this public assistance for mental health care.”

Lambeth told detectives he’d been staying in mental health facilities and a group home before he started staying with his grandparents during the week. This was an arrangement planned by his mom.

Detectives: You said you get this money that comes from Social Security, it goes to your mom, does - what’s the arrangements as far as - do they pay your grandparents too, give them some money for you living there?

Lambeth: Yeah, my mom gives my grandparents money.

It wasn’t a secret that Lambeth stayed with his grandparents. Neither was his history of mental illness. Sheryl Kornman remembered friends of the Gremmlers telling her that the Gremmlers themselves were worried about Christopher Lambeth. Still, they let him stay at their home.

“I think it was their religious beliefs, you know, they believed that everybody is a child of God,” Kornman stated. “And they did tell their friends explicitly, who were very worried about him, we're not going to turn our backs on our grandson. You know, we love him. We know that he's sick and we're not going to turn our backs on him.”

In the interview with Christopher Lambeth, detectives kept pressing him for a motive. One investigator asked what things were like inside the home and whether those conditions led to Lambeth lashing out. Lambeth told them he felt his grandparents were “destructive” to him.

Guilty Except Insane

Christopher Lambeth was ultimately charged with two counts of first-degree murder for killing his grandparents. Lambeth told investigators he stopped taking his medicine before killing his grandparents.

Detective: Do you think you did this because you were off your medication?

Lambeth: No.

Detective: OK, you think it was just ‘cause you wanted to?

Lambeth: Like I said, it was just personal problems.

Detective: OK.

Lambeth: That I don’t want to bring up.

Detective: OK, but you don’t think your not being on your medication had anything to do with it?

Lambeth: No.

Detective: OK, OK.

Lambeth: Not an insane thing to do, it’s not because of my medication.

After nearly two years of court proceedings, Lambeth pleaded Guilty Except Insane to both counts of murder in 2007. Under Arizona law, Guilty Except Insane, or GEI, means a person has a mental disease or defect of such severity that the person did not know the criminal act was wrong.

In the months that followed his arrest for the double murder, court records show Lambeth refused to talk about the crime with his attorney and denied he had any symptoms.

Records show doctors evaluated him and reported he suffered from “delusions” and that he heard “voices that weren’t there.”

Court records claim Lambeth was “unable to function in a legal setting” and at one point, he was deemed “not competent to stand trial.”

Part of that guilty except insane plea meant Christopher Lambeth wouldn’t go to prison. Instead, a judge sentenced him 25 to life at the Arizona State Hospital for treatment.

“The prosecutors decided to agree, because it was pretty obvious that he had a psychotic episode that jail would not be the place for him,’ Sheryl Kornman remembered. “They don't really have the facilities to incarcerate someone who's that ill.”

After Lambeth went to the state hospital to serve his sentence, his mother and his aunt, Carl and Patricia Gremmlers’ daughters, filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the psychiatrist and two mental health agencies that worked with Lambeth before the murders. They accused the doctor and agencies of not doing enough to help Lambeth before the crime. The doctor settled with Lambeth’s family out of court, but the two mental health agencies went to trial.

“Christopher Lambeth was deemed to be 25% responsible,” Sheryl Kornman remembered. “The psychiatrist overseeing his care was 25% responsible. And the other two public pay agencies that were involved in his care were each 25% responsible.”

Court documents back-up that break-down. The out-of-court settlement with the doctor wasn’t made public, but in the case that went to trial, Christopher Lambeth’s mother and aunt were awarded $1.5 million dollars.

12 News tried to contact Christopher Lambeth’s mother for this story but could not reach her. An obituary shows his aunt passed away in 2014. Christopher Lambeth’s sister declined to talk with 12 News.

Despite his 25 to life sentence in the state hospital, Christopher Lambeth would be back in society long before then.

You can catch that story in the next chapter of Locked Inside: Secured starting April 26, 20221 wherever you listen to podcasts.

No one working with or representing Tilda Manor agreed to talk with 12 News at this point in our story.

Christopher Lambeth’s current attorney did not respond to any of our requests for comment at the time this story was published.

Chapter 3 Secured

It’s a complex that spans a few blocks, right on the edge of downtown Phoenix. Most people probably wouldn’t recognize it if they were driving or walking by. From the street, you can see stone and brick buildings and layers of barbed wire encasing parts of the facility. Sometimes, you can catch glimpses of people in bright orange sweat suits walking laps around the yard or doing pushups.

This looks and probably sounds like a prison, but this is different.

It’s the Arizona State Hospital, or ASH as some people call it. It is a complex place where people can be placed for mental health treatment. It doesn’t take in just anybody. There’s a facility for sexually violent people. Then there’s the civil hospital where adults can be court-ordered for treatment if they’re deemed dangerous to themselves or others. There’s also a forensic hospital for certain people who have been involved in the criminal justice system. These people could be awaiting trial, or they could be sentenced to the state hospital for treatment after committing a violent crime, like Christopher Lambeth.

RELATED: Locked Inside: How an Arizona law allowed a man who killed his grandparents to not go to jail

In Locked Inside episode 2: Guilty Except Insane, the 12 News I-Team uncovered that Christopher Lambeth was sentenced 25 to life at the state hospital for treatment, where he was placed under the jurisdiction of the Psychiatric Security Review Board, after he killed his grandparents.

Psychiatric Security Review Board

The Psychiatric Security Review Board, or PSRB, monitors all people who have been deemed guilty except insane. It’s the Board’s decision to determine whether those people stay locked inside the state hospital or whether they’re well enough to be released into the community.

If someone has completed serving their sentence, the Board decides if that person needs more services when they’re let out of the hospital.

The Board typically meets once a month to discuss and make decisions on various cases. There aren’t many visitors at these meetings. Mostly, it’s just attorneys representing people deemed guilty except insane or hospital staff members that can weigh in on a case. And in the age of COVID-19, some of these people just join the Board’s video call instead. It’s not common for members of the public to just drop in.

The stated goal of this law is for people who are deemed guilty except insane to get the help they need at the state hospital and get to a point of stable remission so they can potentially go back into the community.

The Board is tasked with balancing the goal of treating people until they’re in remission, and keeping the public safe from individuals convicted of violent crimes.

Only three states in the nation use psychiatric security review boards: Oregon, Connecticut and Arizona. In Arizona, it manages a very small part of the criminal justice system.

The latest available data from 2020 shows there are 113 people deemed guilty except insane under the PSRB’s jurisdiction. To put that in context, there are more than 33,000 people incarcerated in Arizona prisons at the time of this publication, meaning the 113 convicted people under the Board’s watch represent a very small fraction of people convicted of crimes.

Most patients deemed guilty except insane go before the Board every two years for a status update, where the Board determines if that person should receive privileges on the hospital grounds or eventually be released back into the community. Board meetings are usually when these check-ins happen unless the Board needs to intervene in a case for some other reason.

Until recently, the Board had five members. Three of them were mental health professionals, one worked in probation and parole and the other was a community member. Each board member is appointed by the Governor of Arizona. The Board doesn’t have any oversight, so whatever these five people decide goes.

The people that are guilty except insane are convicted killers or other violent offenders with serious mental health concerns, who at one point posed such a threat to the community that they had to be sentenced to treatment.

The decision to let these people live in the community again should be taken seriously.

“I was shocked to hear that he was let out of the state mental hospital from covering the double murder of his grandparents,” said Sheryl Kornman, the former Tucson Citizen reporter who weighed in on Locked Inside episode 2.

Kornman is talking about Christopher Lambeth who was sentenced to 25 to life at the state hospital for killing his grandparents. Instead, after nine years in the state hospital, he got out, and started living in the community again. Records indicate he’d been living in a group home for a few years before he was arrested and accused of killing Steven Howells at Tilda Manor in April 2021.

“In talking to the friends of the grandparents and the deputies who handled the case, this is a guy that probably needed to be hospitalized for the rest of his life,” Kornman recalled. “Because of his mental illness, he couldn't be trusted to take his own medication. He needed to be supervised 24/7.”

Kornman wrote multiple reports on Christopher Lambeth and the aftermath of his grandparents’ deaths. She had no idea he’d been arrested and charged with murder again or that he’d even been released from the Arizona State Hospital until 12 News reached out to her last summer.

“It doesn't sound like they've dug very deep,” Kornman said, referring to the state’s Psychiatric Security Review Board. “And it also sounds like they ignored the brutality of the murder of his own grandparents, who had been taking care of him almost full time for a couple of years before he killed them. So, I think there was a lack of not understanding of how sick he was, but I think the state board dropped the ball.”

'He takes care of himself completely.'

Christopher Lambeth’s 25 to life sentence to the Arizona State Hospital meant that the PSRB had to approve his every move for the rest of his life, unless he petitioned against that after 25 years.

He was first sentenced to treatment in 2007 and had his first hearing in front of the PSRB in 2009. At that point, the Board ruled he wasn’t well enough for any privileges at the hospital.

By 2010, meeting minutes show that that changed. At that point, Lambeth was granted more freedoms on hospital grounds and could eventually get passes to go off hospital grounds for things like a family visit or a doctor’s appointment.

It stayed this way until the end of 2016 when meeting minutes show Christopher Lambeth was approved to live in the community, meaning he no longer had to live at the state hospital, even though he was still under the PSRB’s watch. His release required 24/7 supervision at a residential facility and required he stick to all of his medications and an outpatient treatment plan.

Christopher Lambeth's conditional release letter:

It seemed that first he was released to the Tucson area and at some point later he was moved to Tilda Manor, although the minutes don’t say exactly when he moved into the Gilbert group home.

In September 2017 he went before the Board again, about nine months after he’d been approved to live in the community.

In audio recorded from that meeting, the Chair of the Board explained why Lambeth was there. Lambeth’s treatment team was asking for less supervision, based on all the success he’d been having in his 24/7 setting. Christopher Lambeth’s sister declined to talk with 12 News about her brother, but she did speak out at that September 2017 PSRB hearing on her brother’s behalf.

She told the Board that “his progress has just been phenomenal,” and that “he takes care of himself completely.”

The audio from the meeting detailed that Christopher Lambeth had a job at an Amazon warehouse in Phoenix and that he played ice hockey on a rec team at a rink in Tempe. His attorney told the Board that he could go to a baseball game with Christopher Lambeth or eat lunch with him.

One Board member asked if there were any concerns for his overnight behavior if he were to be in a place with less supervision. His treatment team told the Board they had no concerns that Lambeth would act out with less supervision and ultimately the Board approved him to move to a flex-care facility that would have 15-16 hours of supervision each day.

The changes didn’t stop there. In September 2018, just one year later, he was back before the Board again. At that point, he hadn’t moved out of Tilda Manor because there weren’t any beds available at any of the facilities in the area offering less supervision.

Still, his team was asking for independent living. That meant Lambeth would live on his own but should have had services available to him to continue his treatment.

Audio from that September 2018 meeting indicates all but one Board member approved this move. The Board member who opposed was the Board’s Chair, Dr. James Clark. He explained that he’d feel more comfortable if Lambeth moved to a home with less supervision first before living independently. But the Board majority ruled, and Christopher Lambeth was approved to live on his own.

“I don’t know what was going on with that guy,” said attorney Nora Greer, referring to Christopher Lambeth’s fast-tracked approval for independent living.

Greer is a defense attorney who, over the years, said she’s represented dozens of people at the state hospital deemed guilty except insane. She said she filled in one time for Christopher Lambeth’s attorney during a status hearing, but otherwise never represented him. She is familiar with his case and knows how the PSRB operates based on her own clients’ experiences.

“I don't know how he got out,” she explained. “I'm kind of surprised.”

Moving from a place with 24-hour supervision to a place with none could be a challenge for anyone required to go to meetings, appointments and stay compliant with medications.

“There's always a risk,” Greer said. “You can relapse and either, you know, hurt yourself or somebody else. The other thing too is if you're not ready, you can't do what you need to do to be successful.”

Each year the PSRB puts out an annual report showing how many people are under its watch, what crimes they committed and how many people were released that year.

It does not detail things like how many murderers are out on release.

The 12 News I-Team analyzed more than two-thousand pages of PSRB files, focusing on nearly 75 cases of people who were released to the community. Within the past five years, we identified at least 13 murderers out on release to the community before their sentences were up, all while they were still supposed to be under the Board’s watch.

The PSRB 2020 annual report:

That data included Christopher Lambeth’s case. It’s possible there could be more murderers out that the Board is still monitoring, but the Board wouldn’t break down that information for 12 News.

“A lot of them are going to get out of the hospital anyway,” Greer explained. “And they should get started on doing stuff that helps them do better when they're in with the rest of us as opposed to being on a locked ward and bang, you're out the next day. And what's going to happen to you? You don't want to see that with these people.”

Just like the PSRB has the power to release people to the community early, it can also take it back. If a person violates the terms of their release, the Board can bring that person back to the state hospital.

12 News asked the Board how often this happens, but it didn’t provide an answer. Instead, the I-Team tried to analyze the data we got in a records request.

Most of the murderers we identified hadn’t killed again.

However, some of the people on release returned to the state hospital for things like not taking their medicine, using illegal drugs or having contraband in a group home. Some of the minutes don’t say why a person was ordered back to the state hospital.

In some cases, others went on to commit another violent crime after their time at the state hospital was up. So, they were no longer under the Board’s watch, but it makes one wonder whether their treatment at the state hospital was really effective.

12 News covered a sad example six years ago.

'She did not deserve to have this happen to her.'

On July 25, 2015, Phoenix Police responded to a brutal crime scene. A woman had been decapitated and her pet dogs were severely injured.

That woman was Trina Heisch. The only suspect was her husband, Kenneth Wakefield. They took him into custody after he gouged out his left eye and self-amputated his arm. He was taken to the hospital before he was taken to jail.

In an interview with Trina’s mother and daughter in 2015, they told 12 News there were warning signs.

The couple had only been there together for 3 months, according to neighbors, who said they often heard yelling and fighting. Police said they responded to the home 5 times before this deadly call and said Wakefield also had a history with drugs. But that morning nothing stopped him from killing Trina.

“There was something really severely wrong with him,” Trina’s mother told 12 News in the days after the murder. “She was going to leave him. She didn’t have time for that.”

Trina Heisch and Kenneth Wakefield met at the Arizona State Hospital.

Both had tried to kill a family member and both were found guilty except insane and both were under the watch of the PSRB, according to the Board’s records.

Trina got out first in 2010 after finishing her sentence at the state hospital. Wakefield’s sentence was up at the end of 2014, but he got at least two chances to go out and live in the community on conditional release before that.

Both times, the PSRB revoked his privilege and brought him back into the state hospital, according to minute entries. The public records don’t say what happened, just that he violated his release orders.

The last time he lost this privilege seemed to be just a few weeks before his sentence ended. He was getting out whether he still needed mental health treatment or not.

“I was never afraid of him,” Trina’s mother said in that 2015 interview. “Except this last time he got out of the hospital. And it wasn’t him. It was totally strange because he wasn’t the same.”

When Wakefield was released, PSRB records show the board wanted him to continue getting treatment, including ongoing supervision. The PSRB asked the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office to start that process, but that didn’t happen and it’s not clear why.

“I questioned whether or not he was released with the right supports and what he needed to be successful,” attorney Nora Greer said.

Greer said she actually represented Trina Heisch while she was sentenced to the state hospital. Greer remembered Trina was artistic and could do really nice water colors.

“And certainly she did not deserve to have this happen to her,” Greer said. “I felt really bad. You feel sad about this, about this stuff happening. It should not happen. But it does.”

Wakefield was charged with second-degree murder and animal cruelty for killing his wife Trina and hurting their two dogs. He wailed during his first court appearance, where he stood in front of a judge with an eye patch and bandaging where he cut off his arm. Listening in, one can’t help but think about his mental health history.

This time he was sentenced to nearly 30 years in prison, not the state hospital. Right now, he’s still serving that sentence. His rap sheet shows he’s been in trouble while in prison with recent infractions for fighting and aggravated assault on a staff member.

'That’s their worst nightmare.'

It’s worth noting that some people don’t have problems when they’re back in the community. After reviewing dozens of cases, the I-Team found that a lot of people try sticking with their treatment plans, showing it’s possible to remain in stable remission.

Sometimes there are tears of joy when people deemed guilty except insane were approved for another level of freedom. Family members sit in on Board meetings and show their support. Attorney Nora Greer’s seen success, too.

She recalled one Pima County client in particular whose Board term ended last year. She said he’s been staying sober, living with his family and running his own business.

“I've worked with clients who've done really well,” Greer said. “You know, they did everything the Board asked them to do, but there aren't a whole lot of those people.”

These changes can also go wrong, which is why each Board decision matters so much.

“Human behavior itself sometimes is not that predictable,” Greer said. “Sometimes people do behave in surprising ways.”

The Board can’t predict the future. But were members doing everything they could to at least come close?

Because the Board was created by a state law, the closest thing it has to oversight is the state legislature, which could change the law and therefore impact the Board.

“I think the Board members do good work, make reasoned decisions, and are very careful to make sure the public is kept safe and protected,” said the Board’s Chairman, Dr. James Clark, in a November 2019 state Senate hearing.

The state Senate was trying to determine what to do with the Board after a state audit in 2018 found the Board was making decisions with inconsistent data, like mental health reports lacking “sufficient details.”

Because of this, the audit claimed it was hard for the Board to make timely and consistent decisions.

The PSRB 2018 state audit:

The Auditor General laid out suggestions on what the Board could fix like creating a set of rules, policies and procedures to follow, and requesting help to publish hearing and decision orders to reduce errors.

The Board claimed it did fix the problems and the state Senate approved the Board to run for another 8 years.

The PSRB declined to talk with 12 News about the Christopher Lambeth case or any follow-up questions.

“What's happened is that they let somebody out, he wasn't properly supervised, and he went out and (allegedly) committed a homicide,” Greer surmised. “You know, to them, that's their worst nightmare.”

A reminder that Christopher Lambeth is facing a murder charge in the death of Steven Howells. He pleaded not guilty to the group home killing and is awaiting trial.

Life doesn’t always mean life

It’s not just people deemed guilty except insane who have to face the PSRB.

Janine Rodriguez has seen firsthand how the Board operates—and it’s not because she wants to. Back in 2010, she said spent the holidays with her family, including her 34-year-old brother Adam Cooley. It was a cheerful time, like the holidays should be. Until her brother went to work the night of December 26th.

Cooley worked security at a strip club in Phoenix.He just switched to man the front door that night when police say a guy inside the club walked outside, beelined to his car, pulled out a gun and started shooting. The shooter hit four people, killing two, including Adam Cooley.

“I don't really like to think about that because he was so quiet and the chaos surrounding his death really hurts my heart because he didn't live his life in chaos,” Rodriguez said.

Ever after all these years, it’s hard for Rodriguez to think back to that day. To think about the way her brother’s life was taken and the person who pulled the trigger.

Phoenix Police discovered the shooter was a man named Gavin McFarlane. He had a history of mental illness and reportedly wanted to see if he had what it took to kill people.

The I-Team's investigation into the PSRB and Adam Cooley's murder:

McFarlane pleaded Guilty Except Insane. And like everyone else who takes that plea, McFarlane didn’t go to prison. Instead, he was sentenced to life at Arizona’s state hospital. But life doesn’t always mean life.

Just a few weeks after Christopher Lambeth was arrested and charged with murder at the group home, Gavin McFarlane’s treatment team requested he get passes to go into the community. He’d have to be supervised if he left, but it’s the first step of many before the Board can approve a full release.

Janine Rodriguez and her family stepped up, joining in on the PSRB meeting, expressing their concerns that this killer should not be released under any circumstance.

In audio from that meeting, an attorney with the county echoed the family’s concerns, accusing the state hospital of copying and pasting reports to try and release people.

The shooter’s team tried 6 months before this to get him privileges, but at that point the Board ruled he wasn’t well enough to get out. Yet, his team was making virtually the same case again.

“How is it possible that an individual that committed his offense at the end of 2010 spends 10 years without any improvement, well with limited improvement he had as of last September, and then now all of a sudden is miraculously all better?” the attorney for the county questioned during the meeting. “That is not believable.”

McFarlane’s attorney denied the accusations, saying the reports repeated themselves because things didn’t change meeting to meeting. But to Cooley’s family’s relief, the PSRB voted to deny McFarlane’s conditional release—at least for now.

RELATED: 'Something is Broken': The penal system for those convicted on the grounds of guilty but insane

His team can continue to push for privileges and his victim’s family will have to face this horrible case over and over again.

Christopher Lambeth’s case didn’t have the same kind of intervention.

Lambeth had reservations about living on his own

Christopher Lambeth’s last Board check-in was in August 2020, about 8 months before the group home killing.

Although Christopher Lambeth had been approved for independent living nearly 2 years before, he still hadn’t left the group home Tilda Manor. He was still under around-the-clock supervision and had been since he’d been released from the state hospital more than 3 years before this. His treatment team explained it had been tough to find a place for him to live.

In audio from that August 2020 hearing, one of Lambeth’s treatment team members said Lambeth wanted to stop taking one of his antipsychotic medications, something he’d been taking since at least 2015 when he was at the state hospital. His treatment team member said it was because of the side effects. She goes on to say that the nurse practitioner who prescribes Lambeth his medications was reluctant to take him off and asked the Board to help make a decision.

In Locked Inside episode 2 we revealed that Lambeth told detectives he wasn’t on his medication when he killed his grandparents. Changing his medications seems like it should be a serious conversation.

The Board’s Chair explained that it wasn’t their call to help make that decision because they’re not involved in his care. But another Board member recommended Lambeth not move to another level of care if there is a medication change made “to make sure that medication change does not come with compensation of his current mental status and the fact that he’s quite stable.”

At that point in the meeting, the Board questioned why they approved Lambeth for independent living. One of Lambeth’s treatment team members weighed in again, saying he had reservations about living on his own.

In the 14-minute hearing, no one seemed to ask Lambeth directly what he wanted to do. There was no discussion of any risk assessment. It’s possible there was a recent risk assessment in Lambeth’s confidential files, but 12 News can’t know for sure without the PSRB answering questions.

Attorney Nora Greer retired over the summer in 2021 and had to turn over all her PSRB cases to whoever else would be taking over her contract. When asked if she had faith in the state’s mental health care system, she didn’t hesitate with her answer.

“No,” Greer said. “Of course not. I don’t think it works really well. We don't put the resources where we need them.

“I don't want to say everybody in there is acting in bad faith because I do think there are people in there who care and really want this stuff to work better,” Greer added. “I think a lot of it is resources. We don't put resources towards what we want to do. So, of course, it's not going to work really well.”

And it’s not just the Board facing criticism.

You can catch that part of our investigation in the next chapter of Locked Inside: Sheltered wherever you listen to podcasts starting on May 3, 2022.

Anyone working with or representing Tilda Manor declined to talk with 12 News at this point in our story. Christopher Lambeth’s sister declined to talk with us for this series. Christopher Lambeth’s attorney at the time of this recording did not respond to our requests for comment. The PSRB declined to comment.

Chapter 4 Sheltered

Lisa Lomeli can still picture the house. How it looked. How it smelled.

“Imagine a rental house that's never been really taken care of,” she said. “And you have loads of people living there that don't take care of anything. That's what the inside of this house looked like. Everything was worn, everything was old, stained, dirty. Like you could clean it a million times and still—just dingy. Very, very, very used.”

Not a very good rating, especially for a place her son was calling home.

“Plus, you know, you've got people with anger issues,” Lisa said. “And there's holes and this and that. So, you don't want to put a ton of money into it. But it was just the bare bones.”

This home she’s describing is the Tilda Manor group home on Wildhorse Drive in Gilbert, Ariz. Staying there was supposed to help her son with his behavioral and mental health concerns.

“All it did was make my son lie and scheme and manipulate to get himself out of there,” she said. “He hated it so much.”

And she never would have imagined that she and her son would unknowingly be exposed to a convicted killer.

Living at Tilda Manor

Lisa never planned for her son to live in a group home.

“I was hoping for a safe, comfortable, somewhat warm environment where he could learn life skills,” Lisa said. “Anger management. Where he could get, you know, the counseling and the information he needed to kind of start his adult life, kind of on his own since at the time he wasn't... allowed to come back to my house.”

We’re not naming her son to protect his privacy, but we can say he’s in his mid-twenties. And we have Lisa’s permission to share what she said happened.

“He's got a few diagnoses,” Lisa shared. “He has high functioning autism, ADHD, bipolar disorder, which he was diagnosed with when he was 10. So, he's had it for a long time. But as he got older, he got much more aggressive. And I had to call the police quite a few times. He tried to hurt himself quite a few times.”

But in June 2019, he didn’t just hurt himself.

“On Father's Day, he just completely lost it,” Lisa said. “And he ended up breaking my arm, giving me a concussion. And so that was it.”

Her son wasn’t charged, but a police report showed he was taken to a hospital for a psych evaluation. And after that, he was court ordered into outpatient treatment. Lisa said the court also ruled he couldn’t live with her because he hurt her, so he was placed at the group home Tilda Manor.

“He was done the minute he walked in,” Lisa remembered. “But he knew he didn't have any place else to go, I didn't have any other place to put him. This was our first time with him as an adult in a government program. And so, I wasn't sure what was available to him and what he could do. So, I was relying on his team.”

Lisa said her son was receiving benefits for what the state calls his “serious mental illness,” or SMI. And typically, that’s how a lot of people come to live in these residential facilities, or group homes. State and federal programs will pay facilities to take in the people that are receiving the benefits.

“It wasn't the support that we expected,” Lisa said of TIlda Manor. “It was supposed to be a learning experience to help him get stable.”

Her son had a rough time transitioning, but he did make a friend on the inside. This friend was almost like an older brother.

“He helped my son navigate,” she said. “'Hey, don't talk to him that way. That's just gonna make things worse.’ He really gave my son some good advice.”

That friend was Christopher Lambeth.

Lisa learned through our news coverage that Lambeth, who helped her son in this tough situation, was arrested for allegedly killing someone else in the house.

“Unbelievable,” Lisa shared. “I know Chris. I've spent quite a bit of time with Chris and he was one of the most mellow, even-tempered fellows there.”

Lisa would try to visit her son in the group home as much as she could, and oftentimes that would include visiting with Chris. She’d take them out on walks and bring them around her other kids. And she said staff would let Lambeth go with her on these outings.

Lisa and her son had no idea Christopher Lambeth was a convicted double murderer after brutally killing his grandparents more than a decade before.

Locked Inside chapter 2: Locked Inside: How an Arizona law allowed a man who killed his grandparents to not go to jail

“I spent a lot of time with them,” she said. “And never, never, never, never, in my wildest dreams, would I have ever, never crossed my mind. He'd be the last person that I would have thought would have done something like that.”

It bothered her a lot that she didn’t know this about Christopher Lambeth. She understood some things were supposed to be private when it came to residents in the home. It’s not clear what Tilda Manor’s policy is on disclosing other resident’s histories, but Lisa wished the staff would have given her some sort of heads up.

“I needed to know,” Lisa shared. “This person has a history of, you know, violent behavior. No, he didn't have to tell me what it was. They didn't have to. But then I could have made the choice myself.”

'Clients are very unpredictable.'

At the time of publication, the owners of Tilda Manor or anyone representing them didn’t agree to talk with us for our series Locked Inside.

However, through public records, the 12 News I-Team was able to track down 23 people who at one point in time over the past few years worked at Tilda Manor. Some of them did not respond or declined to talk.

One woman even said she’d been instructed by Tilda Manor leadership not to talk with a reporter.

But a former manager at Tilda Manor who we're identifying as John, was willing to share what he remembered.

He said he worked at Tilda Manor for six years. He said he started as a behavioral health technician and then worked his way up to a manager with duties like quality assurance, where he made sure the homes were clean and records were kept straight.

“It was great,” John said. “Like I said, I stayed there for six years. If the place is not great and cannot be there for six years. So, it was great. Good work and experience.”

He said he left in 2020 so he’s no longer working at Tilda Manor. But from his view, everyone with the company was always trying their best.

“Mental health,” he said. “That was what we sign up for. Clients are very unpredictable.”

By clients, he means the people who are placed to live at the home, people like Christopher Lambeth or Lisa’s son. He said most of the residents come to the home from the state hospital or other hospitals with psychiatric wards. Insurers like Medicaid or AHCCCS could reach out to Tilda Manor and provide the prospective resident’s case file.

Then, he said, Tilda Manor would screen the person by checking things like their diagnoses, behaviors and medical records. If it’s a fit and there’s a bed available, the person could be placed at the group home.

John said they don’t check to see if a person would be compatible with other people in the home. So, it’s possible someone placed there after a violent incident could be living there with someone who was not violent.

Records indicate it’s possible someone could also be transferred out of the home if a problem came up while a person was living at the house.

Police records show Tilda Manor on Wildhorse Drive has capacity for 10 beds, meaning 10 residents. And when it comes to around the clock staffing, John said they would have a 1:5 ratio. If a home had more than five residents, there should be at least two staff members there.

These staff members are usually behavioral health technicians, or people who are supposed to help give out medications, help residents with cooking, cleaning, preparing for appointments and other parts of their treatment plans. John said they would train staff in mental health, substance abuse and how to deal with clients in different situations, like what to do if a person was having a violent episode.

“They're supposed to know what's going on so you can watch and see any change in behavior or anything,” he said.

Lisa said she saw discrepancies in staffing when she would visit her son in the home.

“During the day they had anywhere from one to four workers there,” she remembered. “But a lot of times they were on their phones or they were clustered together watching TV. They pretty much just let the people do what they wanted.”

Lisa also recalled a time when her son needed treatment for a skin condition. She said the home wouldn’t provide transportation to a hospital, so they told him to call his mom.

“The woman working said, ‘I can't leave,’” Lisa said “‘I can't leave less than two people here. So you're going to have to find your own way. Have your mom come pick you up.’”

But Lisa didn’t live close by. She said her son wound up taking an ambulance to the hospital. After he was done with the visit, he called the staff at Tilda Manor who told him again they couldn’t give him a ride, according to Lisa. She was floored. The whole point of having him in a home like this was for people to watch her son and make sure he was sticking with his treatment plan—not leave him hanging when he needed a ride.

“So, I found it very odd then that I would go there and sometimes there'd be only one worker there,” she said. “Because one of the workers had to run out and go pick her children up from school, or whatever. So that wasn't consistent either. When they felt they needed to do it for themselves, they would go. But when it was not convenient for them, they couldn't help.”

At this point, Lisa said she wasn’t her son’s legal guardian. He was an adult and Lisa said his treatment team from the state were the ones to make decisions about his care.

She said her son’s final straw was when he had an incident with a resident that prompted him to report a complaint to Adult Protective Services. Days later, she said her son was moved to another home.

12 News asked APS about this, but they declined to answer questions, citing privacy laws.

“And I would say probably creates an environment that could be unsafe for you know, the workers, but also the residents,” Lisa said.

'We are not qualified…'

The 12 News I-Team did speak with one other former Tilda Manor employee who wanted to remain anonymous.

She said she worked at Tilda Manor for about three years and would rotate between all of Tilda Manor’s five houses based on staffing needs.

In her role she said she’d serve residents their medications, drive them to appointments, and make sure they kept up with hygiene. They were supposed to help build independent living skills. She remembered being called in to cover shifts a lot and often felt overworked and overwhelmed.

She’d never worked in this field before and learned a lot on the job on how to care for people dealing with mental illnesses. She said they did get training on how to handle incidents with residents.

But talking about it and being face to face in a situation are two different things.

“Do this, do that,” she remembered.

This former employee said there were always at least two staff members working, sometimes three or four, and always two overnight. But she admitted that sometimes she felt she didn’t have the right training to handle this job and that she felt she wasn’t qualified to handle certain behaviors or diagnoses.

“We are not qualified to manage it,” she expressed.

Sometimes she said a resident would tell her they wanted to kill themselves and she wouldn’t know what to say. She said she’d do all she could to make a situation calm, but things could escalate quickly.

She remembered one time, when a resident came back from an outing. She was pregnant at the time and out of nowhere, she said the resident tried to punch her. He wound up hitting the wall instead.

That scary situation and the hectic schedule were some of the reasons that ultimately led her to quit her job at Tilda Manor.

“In a normal household, those situations wouldn't come up,” Lisa Lomeli said. “But when you're in a situation where you have a bunch of volatile people, all together in a small place. And even just one of them by themselves could be volatile and difficult to deal with. But when you have a whole bunch of them together, and you don't know how to do any of this stuff, then situations just escalate. And it's just not enough. Not enough help.”

When John thinks back on his time at Tilda Manor, he felt he and the other staff members really made a positive impact. He said he saw a lot of people go through their programs and step down into lower levels of care or even independent living.

Again, no one who currently works at Tilda Manor would talk to us, so we’ve never been able to ask them about any success stories. John assured us that there were some. But as he said before, the people living in these homes can be unpredictable.

John explained that if a person was being violent or a situation got to a point where a staff member couldn’t handle it, protocol is to call 911. They weren’t allowed to lay a hand on the residents.

“And if, if you're a tiny little woman or man and you don't have any skills in breaking up fights or walking somebody through a mental breakdown, or somebody that's having a seizure, and all you can do is dial 911, your job is going to be so, so incredibly hard,” Lisa Lomeli said.

'How did they let this happen?'

Both John and the other former employee we talked to remembered Christopher Lambeth. They also knew his background, how he killed his grandparents.

John and the other former worker told us Lambeth was a model resident. He always took his medications. He’d help clean around the house. He’d play hockey. He’d visit with his sister. He didn’t have any angry outbursts. He seemed content.

“I was shocked,” John said, of learning Christopher Lambeth was accused of killing Steven Howells. “Because Christopher is one of the oldest clients there. I've worked with him, he was respectful. He did everything [he] was supposed to do.”

John also said he talked with some of the staff after the killing and was told Christopher Lambeth was supposed to move out that day, but wasn’t ready to leave the home. It was the same thing we heard at the PSRB meeting. And the same thing police suspected when they walked through the house after it turned into a crime scene and noticed his room wasn’t packed up.

It still perplexes Lisa.

“I still think there's no way Chris would have done something like that without some huge mitigating factors,” she shared. “I don't know what they are. I can guess. But I was floored. So surprised. I want to go see him. ‘Chris, what happened?’ He calls me mom. I'm just still—how do they let this happen? That’s what I want to know. How did they let this happen?”

From Lisa’s view, this home was set up to fail.

To her, there was a disconnect in how the staff were trained, how they communicated, how people were placed there, how Tilda Manor ran the house.

“I don't want anybody else having to go through this,” Lisa shared. “Whether they flip out and do something terrible or whether something terrible gets done to them.”

The 12 News I-Team tracked down both of the employees working the morning of the killing at their homes back in September 2021. At that time, both were still working for Tilda Manor and both ultimately declined to talk with us.

A state investigation later found that those two employees did break a very big rule. And that wasn’t only problem going on inside that house.

You can catch the next part of our story in the next chapter of Locked Inside: Safe Space starting May 10, 2022, wherever you listen to podcasts.

Anyone working with or representing Tilda Manor declined to talk with 12 News at this point in our story.

Christopher Lambeth’s current attorney did not respond to any of our requests for comment at the time this story was published.

Chapter 5 Safe space

Like most of his neighbors, Chris Lineberry woke up to a street filled with police cars on April 12, 2021. He lives down the road from the Tilda Manor on Wildhorse Drive in Gilbert, Arizona.

“Seeing eight police cars and coroner's van and, you know, the medical inspector and all those other people at a house for the whole day,” he explained.

He knew Tilda Manor was a group home - but once he learned someone was killed inside, he was stunned. And he had no idea Christopher Lambeth, someone with a double murder conviction, lived down the street.

“I obviously am concerned about the safety and well-being of me, my family, our neighbors, but also the other residents who live in that home,” he shared. “The fact that somebody who was convicted of homicide twice was put in a residential area 500 and some feet away from a school is really disturbing to me.”

He’s referring to the elementary school around the corner from Tilda Manor. He also pointed out that a lot of families in this neighborhood have kids.

“And it's terrifying,” he said. “I mean, you know, we have kids all up and down this street. I think about people who are more vulnerable. And obviously, some of the other individuals who live in this home are vulnerable, and what was in place to keep them safe? You know, my issue is not with the residents. It's with the way that this home was run. And the fact that this happened, and nobody in the neighborhood knew that there was somebody with that kind of record living there.”

It bothered him that somehow a killing happened and it seemed like no one was doing anything in the immediate aftermath. So, he started making calls. His HOA. The Mayor’s office. The state health department. His state representatives.

He read Gilbert’s town code line by line and found that the home could potentially be violating two rules: one, stating that group home signage can’t be visible from the street, and another, stating that the group home shouldn’t house any person who could be a direct threat to the health and safety of others.

Other neighbors echoed his concerns.

Days, then weeks passed, and they weren’t sure what to do next. It seemed like residents were allowed to move back into the home in the hours after police left the crime scene. And from the outside looking in, everything seemed to be operating like it was before.

“There's got to be accountability,” Lineberry stated. “In a neighborhood with an HOA, you can get yourself into trouble if you don't pull your weeds or take your trash can in early enough."

The ball is in the court of the people who make decisions…”

In an effort to exhaust all his options, he wrote down his concerns and prepared to make some remarks at the next town council meeting on the first Tuesday in May.

“I’ve never spoken out at a town council meeting,” he started, as he addressed Town Council. “I say that to let you know how important this issue is to me. I live just down the road from the group home where a man was bludgeoned, stomped, beaten and strangled to death…”

He continued to share how the details of the killing released by police impacted him and his neighbors.

“This shouldn’t be happening,” he closed. “There’s direct violations of Gilbert zoning ordinances and they should be held accountable and shut down. The ball is in the court of people who make decisions on these kinds of matters and I believe that would be all of you to a certain extent. So, thank you for the opportunity to share my concern.”

The five town council members, mayor and vice mayor are not allowed to comment on the matters brought up during the public comments section. But 12 News went and spoke with Gilbert Mayor Brigette Peterson after the meeting.

And it turned out, she was just as frustrated as Chris and his neighbors. She said her office had been fielding concerns after the killing, but her hands were tied. Even though it’s part of Gilbert’s town code, she said it should be the state ensuring rules are followed as it’s a state-licensed group home.

“They should be shutting the home down in my opinion,” she said after the May 2021 meeting.

Her position hadn’t changed in September 2021 when she sat down with 12 News for an interview.

“I would like to see this home closed down,” she said. “I think that when you have an issue to this extent, in a recovery residence like this, there should be no question that it should shut down. And if the owner would be willing to do that, I would be very pleased with that.”

The owners are listed as Samuel and Grace Ashu in Arizona business records.

The records show Grace Ashu registered Tilda Manor, Inc as a business in 2003 as a domestic nonprofit organization.

She’s listed as the president, Samuel the vice president. They’re both listed as directors of the five Tilda Manor group home locations. There were three in Gilbert and two in nearby Mesa. All were licensed as behavioral health facilities by the state.

Grace and Samuel Ashu declined to talk with 12 News when we asked them for a comment in the days after the group home killing.

In the months that followed the murder investigation, 12 News reached out to Tilda Manor multiple times through email and phone and no one ever agreed to talk with us for this series.

And the murder investigation at Wildhorse Drive was just the tip of the iceberg when it came to police calls at Tilda Manor facilities.

High volume of police calls

There are more than 80 behavioral health group homes in Gilbert, and according to Mayor Peterson and police data, Tilda Manor is in the top 10 list when it comes to police calls. In a records request, 12 News obtained call data from Gilbert Police from 2017 to September 2021.

The Wildhorse Drive location had 91 police calls over that period of time, coming in at number 8 in the top 10.

Another Tilda Manor location in Gilbert ranked even higher, with 110 calls over the 4-year period.

A different company, with four group home locations in town, took the top two spots. All of that company’s locations combined had a total of 650 police calls over a 4-year period, averaging more than three calls per week.

“And anytime the PD is spending time at a home like this, they're not able to be out on the streets for other things that are going on in our community,” Mayor Peterson said. “And so, it's always taxing on our resources for them. And I don't like when they know these homes by heart. they shouldn't have to know these locations like that. And it's just an unfortunate situation, that we have bad actors in some of these businesses.”

The 12 News I-Team pulled Tilda Manor’s call data in Mesa to compare.

Mesa police turned over their records from 2018 to May 2021. In that two and a half year time, Mesa Police responded to the two Tilda Manor group homes a combined 176 times.

Some of those calls were dismissed, but others turned into investigations.

The majority of calls are missing persons cases.

In one case, according to the police reports, a man with bipolar disorder who had manic episodes, was reported missing four times in one week. One of those times, reports say he didn’t return to the home until the next morning.

Another example includes a woman diagnosed with schizophrenia who was reported missing four times in one year. In one of those instances, Grace Ashu, the company’s owner, told police she didn’t report it for an hour because she didn’t realize the woman was missing.

And another time, a staff member watched the resident walk away, telling police she couldn’t leave the other residents to go after her.

This lines up with what a former Tilda Manor staff member who spoke out in Locked Inside episode four, told 12 News. He explained that staff weren’t allowed to touch the residents, according to Tilda Manor’s policy.

Other Mesa police records since 2018 show cases of violence, including one resident arrested for attacking another and another case where a resident punched a staff member in the face.

Once, a resident was rushed to the hospital after trying to kill himself with a razor given to him by a staff member.

These same types of calls were the ones being reported at the Wildhorse Drive Tilda Manor in Gilbert, much to Mayor Peterson’s dismay.

“In this home specifically, it was a mix,” she said. “There's been attempted suicides, there's been fights, there's been mental health issues.”

Gilbert police records show that there were two calls for assault at the home less than a month before Steven Howells was killed. Neither involved Christopher Lambeth, but the first call came in March after a resident allegedly punched a staff member.