GILBERT, Ariz. — Like most of his neighbors, Chris Lineberry woke up to a street filled with police cars on April 12, 2021. He lives down the road from the Tilda Manor on Wildhorse Drive in Gilbert, Arizona.

“Seeing eight police cars and coroner's van and, you know, the medical inspector and all those other people at a house for the whole day,” he explained.

He knew Tilda Manor was a group home, but once he learned someone was killed inside, he was stunned. And he had no idea Christopher Lambeth, someone with a double murder conviction, lived down the street.

“I obviously am concerned about the safety and well-being of me, my family, our neighbors, but also the other residents who live in that home,” he shared. “The fact that somebody who was convicted of homicide twice was put in a residential area 500 and some feet away from a school is really disturbing to me.”

He’s referring to the elementary school around the corner from Tilda Manor. He also pointed out that a lot of families in this neighborhood have kids.

“And it's terrifying,” he said. “I mean, you know, we have kids all up and down this street. I think about people who are more vulnerable. And obviously, some of the other individuals who live in this home are vulnerable, and what was in place to keep them safe? You know, my issue is not with the residents. It's with the way that this home was run. And the fact that this happened, and nobody in the neighborhood knew that there was somebody with that kind of record living there.”

It bothered him that somehow a killing happened and it seemed like no one was doing anything in the immediate aftermath. So, he started making calls. His HOA. The Mayor’s office. The state health department. His state representatives.

He read Gilbert’s town code line by line and found that the home could potentially be violating two rules: one, stating that group home signage can’t be visible from the street, and another, stating that the group home shouldn’t house any person who could be a direct threat to the health and safety of others.

Other neighbors echoed his concerns.

Days, then weeks passed, and they weren’t sure what to do next. It seemed like residents were allowed to go back into the home in the hours after police left the crime scene. And from the outside looking in, everything seemed to be operating like it was before.

“There's got to be accountability,” Lineberry stated. “In a neighborhood with an HOA, you can get yourself into trouble if you don't pull your weeds or take your trash can in early enough."

The ball is in the court of the people who make decisions…”

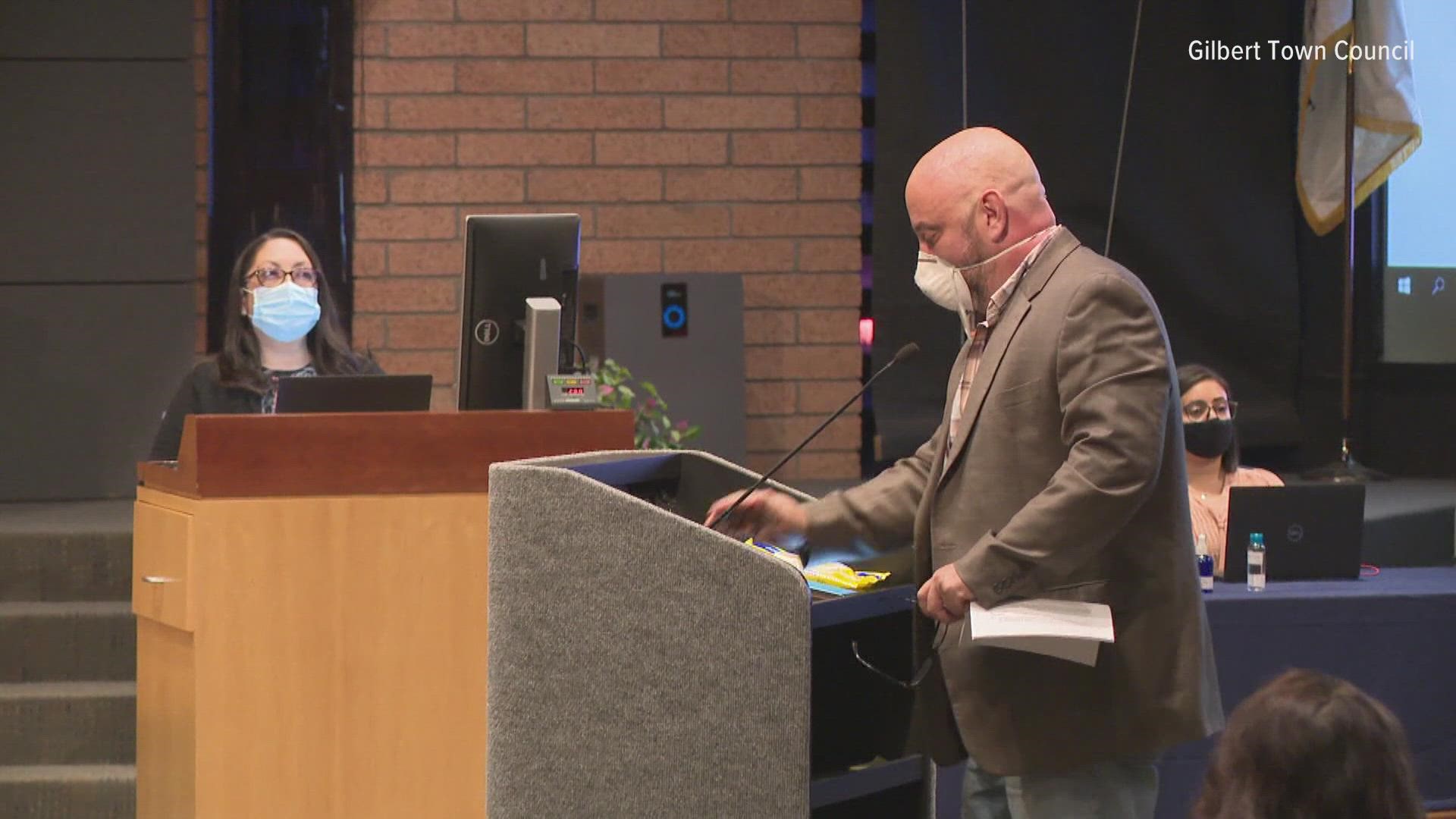

In an effort to exhaust all his options, he wrote down his concerns and prepared to make some remarks at the next town council meeting on the first Tuesday in May.

“I’ve never spoken out at a town council meeting,” he started, as he addressed Town Council. “I say that to let you know how important this issue is to me. I live just down the road from the group home where a man was bludgeoned, stomped, beaten and strangled to death…”

He continued to share how the details of the killing released by police impacted him and his neighbors.

“This shouldn’t be happening,” he closed. “There’s direct violations of Gilbert zoning ordinances and they should be held accountable and shut down. The ball is in the court of people who make decisions on these kinds of matters and I believe that would be all of you to a certain extent. So, thank you for the opportunity to share my concern.”

The five town council members, mayor and vice mayor are not allowed to comment on the matters brought up during the public comments section. But 12 News went and spoke with Gilbert Mayor Brigette Peterson after the meeting.

And it turned out, she was just as frustrated as Chris and his neighbors. She said her office had been fielding concerns after the killing, but her hands were tied. Even though it’s part of Gilbert’s town code, she said it should be the state ensuring rules are followed as it’s a state-licensed group home.

“They should be shutting the home down in my opinion,” she said after the May 2021 meeting.

Her position hadn’t changed in September 2021 when she sat down with 12 News for an interview.

“I would like to see this home closed down,” she said. “I think that when you have an issue to this extent, in a recovery residence like this, there should be no question that it should shut down. And if the owner would be willing to do that, I would be very pleased with that.”

The owners are listed as Samuel and Grace Ashu in Arizona business records.

The records show Grace Ashu registered Tilda Manor, Inc as a business in 2003 as a domestic nonprofit organization.

She’s listed as the president, Samuel the vice president. They’re both listed as directors of the five Tilda Manor group home locations. There were three in Gilbert and two in nearby Mesa. All were licensed as behavioral health facilities by the state.

Grace and Samuel Ashu declined to talk with 12 News when we asked them for a comment in the days after the group home killing.

In the months that followed the murder investigation, 12 News reached out to Tilda Manor multiple times through email and phone and no one ever agreed to talk with us for this series.

And the murder investigation at Wildhorse Drive was just the tip of the iceberg when it came to police calls at Tilda Manor facilities.

High volume of police calls

There are more than 80 behavioral health group homes in Gilbert, and according to Mayor Peterson and police data, Tilda Manor is in the top 10 list when it comes to police calls. In a records request, 12 News obtained call data from Gilbert Police from the beginning of 2017 to September 2021.

The Wildhorse Drive location had 91 police calls over that period of time, coming in at number 8 in the top 10.

Another Tilda Manor location in Gilbert ranked even higher, with 110 calls over the 4-year period.

A different company, with four group home locations in town, took the top two spots. All of that company’s locations combined had a total of 650 police calls over a 4-year period, averaging more than three calls per week.

“And anytime the PD is spending time at a home like this, they're not able to be out on the streets for other things that are going on in our community,” Mayor Peterson said. “And so, it's always taxing on our resources for them. And I don't like when they know these homes by heart. they shouldn't have to know these locations like that. And it's just an unfortunate situation, that we have bad actors in some of these businesses.”

The 12 News I-Team pulled Tilda Manor’s call data in Mesa to compare.

Mesa police turned over their records from 2018 to May 2021. In that two and a half year time, Mesa Police responded to the two Tilda Manor group homes a combined 176 times.

Some of those calls were dismissed, but others turned into investigations.

The majority of calls are missing persons cases.

In one case, according to the police reports, a man with bipolar disorder who had manic episodes was reported missing four times in one week. One of those times, reports say he didn’t return to the home until the next morning.

Another example includes a woman diagnosed with schizophrenia who was reported missing four times in one year. In one of those instances, Grace Ashu, the company’s owner, told police she didn’t report it for an hour because she didn’t realize the woman was missing.

And another time, a staff member watched the resident walk away, telling police she couldn’t leave the other residents to go after her.

This lines up with what a former Tilda Manor staff member who spoke out in Locked Inside episode four told 12 News. He explained that staff weren’t allowed to touch the residents, according to Tilda Manor’s policy.

Other Mesa police records since 2018 showcase violence, including one resident arrested for attacking another and another case where a resident punched a staff member in the face.

Once, a resident was rushed to the hospital after trying to kill himself with a razor given to him by a staff member.

These same types of calls were the ones being reported at the Wildhorse Drive Tilda Manor in Gilbert, much to Mayor Peterson’s dismay.

“In this home specifically, it was a mix,” she said. “There's been attempted suicides, there's been fights, there's been mental health issues.”

Gilbert police records show that there were two calls for assault at the home less than a month before Steven Howells was killed. Neither involved Christopher Lambeth, but the first call came in March after a resident allegedly punched a staff member.

The very next day, that same resident reportedly assaulted staff again and then assaulted an officer when Gilbert police responded, according to the reports.

About two weeks after Steven Howells’ death, police were called to that home again after a resident went missing. That report said a staff member told police it looked like the resident used a chair to get over the property's fence.

“It doesn’t seem like a very safe environment,” said neighbor Chris Lineberry. “To me, that's a sign that there's something bigger happening there. And the residents who live there, obviously, many of them have issues, but they need help with those issues.”

Questions about inspections

Arizona’s Department of Health Services said there are around 3,800 facilities under its licensing umbrella. At the time of this writing, 870 of those facilities are listed as behavioral health facilities for adults like Tilda Manor.

Anyone can start a group home in Arizona so long as they have the space, pass an inspection and write a set of policies and procedures that the state approves.

And if that criteria is met, the state has to issue the license, with very few exceptions.

“For example, if the department has already revoked your licenses in the past and already has a history and you have a history of non-compliance with our rules, we may deny that license,” said Colby Bower.

Bower left his job as an assistant director overseeing licensing with ADHS in early 2022, but still held the position when he interviewed with 12 News in October 2021. He oversaw licensing for the things like medical marijuana shops, hospitals and behavioral health facilities like Tilda Manor. ADHS said another person stepped into his role after Bower left.

When we interviewed Bower, he told us he couldn’t talk specifics about the murder investigation at Tilda Manor, but could weigh in generally about licensing.

State surveyors are supposed to go out and inspect homes once a year, but that might not always happen. Some facilities are accredited, meaning an outside agency will come and inspect the home instead of the state.

The state typically does not review these results.

The only other time the state would show up to inspect a group home could be if there was a complaint.

“It could be anything,” Bower explained. “A resident may not feel like they're getting the right kinds of foods. We may get complaints from family members that may go visit them to say I don't like the environment that they're in right now. It may seem unsafe. And so, we get all kinds of complaints.”

The type of complaint determines how quickly inspectors go out and how they respond. Bower said ADHS surveyors are supposed to go out right away if residents could be in danger. But something more minor, like a broken towel rod, might take longer to address.

If the state does find a home to be “non-compliant,” meaning they’re breaking one or several rules, the state can issue a notice of deficiency or cite the facility. In most cases, facilities will have a specified period of time to fix the problem or problems or potentially pay a fine.

The results of all the inspections done by the state are supposed to be public through a health department website called AZ Care Check. But AZ Care Check doesn’t show active investigations or complaints that have been dismissed. The records that are published on AZ Care Check are purged after three years due to retention laws.

So, if a person had a loved one in one of these facilities and wanted to know more or a neighbor wanted to look for potential past problems, the scope would be limited.

A long list of problems

A murder investigation at a group home is one of those times that prompted one of those day-of inspections from the state.

The Tilda Manor on Wildhorse Drive had a few recent inspections before, with a few citations listed on AZ Care Check. Liked a December 2020 Civil Penalty that said Tilda Manor was fined $500 for leaving a resident alone, according to the state’s records. Staff reportedly took other residents on an outing and left one resident alone at the house.

The inspection report completed in June 2021, in the wake of Steven Howells’ death, was much more detailed.

The state-issued citations for 23 violations in all, from little things to glaring problems, according to the state’s investigation report.

For example, Tilda Manor was caught advertising services they weren’t qualified to provide, like elderly and LGBTQ programs.

At least six of the nine residents living in the home, including Christopher Lambeth, were flagged to be a danger to self or a danger to others, which should have been considered before they were placed at Tilda Manor.

Another resident’s file said they served prison time for assaulting an officer, yet they weren’t flagged to be a danger to others.

In all, the investigation found that seven out of nine residents weren’t screened properly and shouldn’t have been admitted to this home.

Neighbor Chris Lineberry couldn’t believe what he was reading when he saw a copy.

“And it did result in a danger to our neighborhood,” he expressed. “It resulted in a danger to the employees. And it obviously resulted in a danger to the residents because one of them was murdered by another one, allegedly, by another one of the residents there. And when you read that report, it's just damning.”

There’s more.

The state found some of the residents weren’t receiving proper counseling, including Lambeth, whose treatment plan wasn’t even up to date. In the months leading up to Steven Howells’ death, Lambeth’s behavior started to change. He expressed concerns about moving out, amid pressure from his treatment team. He had reportedly become more isolated. He’d skip meals, stop talking to other people in the home. He stopped going to hockey. Staff said this was because he was sick and had a physical injury.

Notes in Lambeth’s file showed he would sometimes have hallucinations linked to dangerous commands and homicidal behavior. Notes said he had signs of anxiety and depression, but there weren’t any interventions.

Staff said they didn’t bother him because they “wanted to respect his wishes by letting him isolate from others.”

The state found Tilda Manor’s records showed Lambeth had a decrease in therapy sessions before Steven Howells’ death and that Lambeth’s medical records showed one of his medications ran out and seemingly wasn’t replenished for about a month.

Gilbert police apparently took some of Lambeth’s files in its investigation, so the state reported it didn’t have a clear picture when the inspection was done.

Without those records, the state investigator wrote it’s not clear how long he went without his medicine.

“I think you can judge a society a lot based on how we take care of people who aren't able to take care of themselves, or who need extra assistance,” Lineberry said. “And to allow them to stay in business and allow them to continue to be neglectful and derelict in their duty, as the report says, is really a travesty.”

In its report, the state found the two employees working the morning of Steven Howells’ death violated group home policy when they left a reportedly dangerous Christopher Lambeth inside the house, unsupervised, with eight other residents.

We reported back in Locked Inside episode one, Murder at Tilda Manor, that these two employees fled after Lambeth allegedly tried to attack them and they got locked outside.

One was a behavioral health technician, whose file said he had a high school diploma and two years of behavioral health experience before Tilda Manor.

The other was a behavioral health paraprofessional who had only been working at Tilda Manor since August 2020. This person’s file said he was a teacher from 2015 to 2017 and had a college degree in accounting and economics. Nothing in his file showed he had any experience or qualifications to work in behavioral health.

In fact, the state’s investigation found there were problems with nearly all the employee files. Some didn’t have documented CPR training, some didn’t show that employees were vetted for these roles or got proper training to work in behavioral health.

One of the employees working the morning of the killing told the state they had no training on dealing with residents’ diagnoses or recognizing signs of a potential relapse.

And after a review of Tilda Manor’s rule book, the state found some of the group homes own rules had been out of compliance with the state since 2013.

Raising the question: How can that even be possible if the state was doing regular inspections?

The state’s own records show the home was inspected in November 2020, which led to the state citing Tilda Manor for leaving a resident alone. That was less than six months before the killing.

“It can happen for a variety of reasons,” Colby Bower, formerly with ADHS, explained.

“If it's an annual inspection, our inspectors are going in there and they're looking generally at things and so they may not see some violation with paperwork for example,” Bower said. “Or they may check for example, five staff records and not all, you know, maybe the facility has 10 staff members, and we will check half of those files. And so we may miss that one staff member doesn't have all the training they're supposed to have. That can happen. So those inspections are really just a spot check.”

And if the inspection is complaint driven, he said inspectors will narrow their focus to the allegation, not necessarily the home as a whole. 12 News asked Bower whether the state was doing enough during inspections.

“‘Inspections and being on site is - it's invaluable,” Bower stated. “We have to go out and do that work. But the other piece of it is, really, those complaints drive a lot of what we're able to uncover. And so if there are neighbors or neighborhoods that are having issues with the facility, please let us know, anybody can complain at any time.” “

Will Humble, the state’s former ADHS director, weighed in in the aftermath of the murder investigation.

“When you look at an incident like this, it's almost never a one-off,” Humble said. “It's usually a systemic problem.”

He served six years as state health director, meaning he oversaw everything, including group home licensing.

“I mean, you need to have the resources in order to staff up appropriately so that you can follow up on complaints,” he said. “And when you don't have those kinds of resources in place, you see it manifested in the kinds of incidents that we're talking about today. In this case, the tragedy of Tilda.”

And in Humble’s view, the situation at Tilda Manor shouldn’t have happened.

“What we're talking about now is the response,” he said. “I've always been more interested in prevention. The prevention side is what I was always passionate about. And that means getting the resources that you need so that you have adequate staffing so that you can follow up on complaint investigations. Before bad things like this happen. Once bad things like this happen, you're not just responding to a bad event. You're not preventing the bad event.”

To Humble, the licensing department doesn’t have the staffing to handle inspections and complaints adequately.

He points to a 2019 state audit that found the state health department failed to investigate some long-term care facility complaints and reports in a timely fashion, or at all. This part of the audit does not detail behavioral health facilities. This is specific to long-term care facilities like nursing homes.

But Humble thinks it still sheds light on licensing as a whole.

“I know that that used to be my job, it was something that I took very seriously,” Humble said. “It's a big responsibility. And if you're going to have a big responsibility, you need to make sure that you have the resources to carry that responsibility out. And there aren't the resources right now to do it right.”

When we checked in September 2021, the state said it had about 300 surveyors, with around 30 of them handling residential facilities like group homes.

Each of these surveyors might have 90 facilities on their plate, which Colby Bower said was pretty standard.

“We have a great staff and they do tremendous work,” Bower explained. “I can't tell you the number of weekends our staff has spent at facilities, late at night, staying there until a dangerous situation can be remediated.”

Bower put it to the public, saying the best way for surveyors to get to the root of a problem is for complaints to be specific.

“When we get those complaints from the public,” he said. “When they're specific and we can really pinpoint down what the issue is, that is when our inspectors can do their best work and really drill down into what caused the situation.”

“When it comes to the health and especially the safety of the residents within the home, that's clearly 100% the responsibility of the Arizona Department of Health Services,” Humble said.

Colby Bower had a different answer.

“By Arizona law, it's the folks that actually run the homes,” Bower said. “And, you know, ultimately, the licensees are responsible for that. The state tries to provide those minimum safety standards for those licensees to operate under. But really, the care and treatment of those individuals is regulated by a whole host of folks. Insurance carriers, for example, have different standards for their covered lives. You know, there's a whole host of agencies and things that have a role to play here. Our role is really to license that facility and to make sure that the facility is operating under those standards.”

One thing Colby Bower and Will Humble do agree on is that revoking a license is a last resort for the state health department.

There are not a lot of places people with serious mental illnesses can go for help in Arizona. The state hospital and psychiatric units at other hospitals have a limited number of beds. Many people wind up in the prison system. Others end up on the streets. For years, Christopher Lambeth’s team said they struggled to find him a bed in a different facility, whether he wanted to move or not.

Where is the line? At what point do problems outweigh the positives a group home can bring?

These are questions with no clear answers as the state handles homes case by case.

A push for change in Gilbert

Since the killing at Tilda Manor, Gilbert Mayor Brigette Peterson has been wondering where things could have gone differently.

“I think that group homes have a place in our community,” she said. “And I think it comes down to them being operated well.”

She’s since called meetings with her police chief and the Department of Health Services. They’ve changed their town policy where police will have to report all calls to group homes to the state.

The state typically doesn’t collect this data and police departments don’t have to report it to licensing.

“I wanted to know that there are ways for us to help those residents,” she said. “And there's ways for my police department to help ADHS at the same time. And maybe even my fire department because they do calls on these residences also.”

Lineberry is still holding out hope that the state will step in and revoke Tilda Manor’s license.

It was frustrating for him that Tilda Manor could still operate after the murder and that people were still allowed to live inside.

“How did it happen?” Lineberry questioned. “Like, how was an agency given the freedom to house people who they weren't qualified to house? How was there that big of a gap or hole in the system that people were able to fall through? And these aren't cracks. These are wide, wide gaps. And how is it that people were able to fall through those gaps, and as a result of falling through those gaps, man losing his life?”

We asked Tilda Manor if the two employees found to have violated protocol the morning of the murder ever reprimanded. Tilda Manor didn’t comment.

As of now, Christopher Lambeth is the only one charged in this case.

“And my issue is not with the individuals who live in that home,” Lineberry said. “They need help, obviously, that's why they're there. My issue is with the lack of professionalism, the lack of integrity, the lack of oversight.”

Lambeth pleaded not guilty to the murder charge in Steven Howells’ death. He’s set for a trial in June 2022.

You can catch the last scheduled chapter of our story Locked Inside: Intervention starting May 17, 2022, wherever you listen to podcasts.

No one working with or representing Tilda Manor agreed to talk with 12 News at the time of publication point in our story.

Christopher Lambeth’s current attorney did not respond to any of our requests for comment at the time this story was published.

12 News on YouTube

Locked Inside, a new 12-News I-Team and VAULT Studios podcast, follows the harrowing and heartbreaking story of Christopher Lambeth and those who crossed his path along the way.