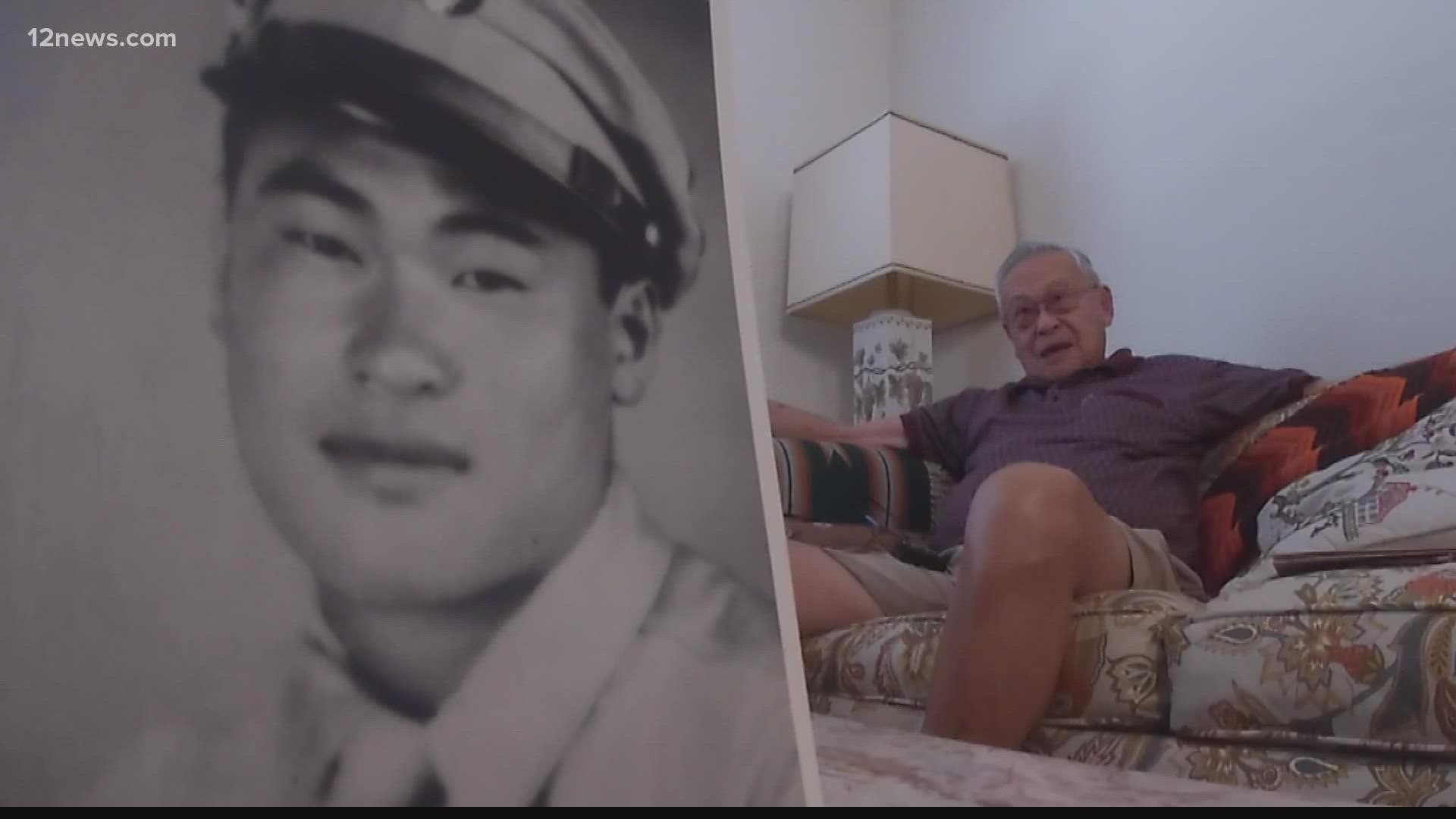

ARIZONA, USA — Editor's note: The above video aired during a previous broadcast.

Rubble, dust and a plaque just off Interstate 10 is all that remains of a site where the United States military forcibly moved thousands of Japanese-Americans during WWII.

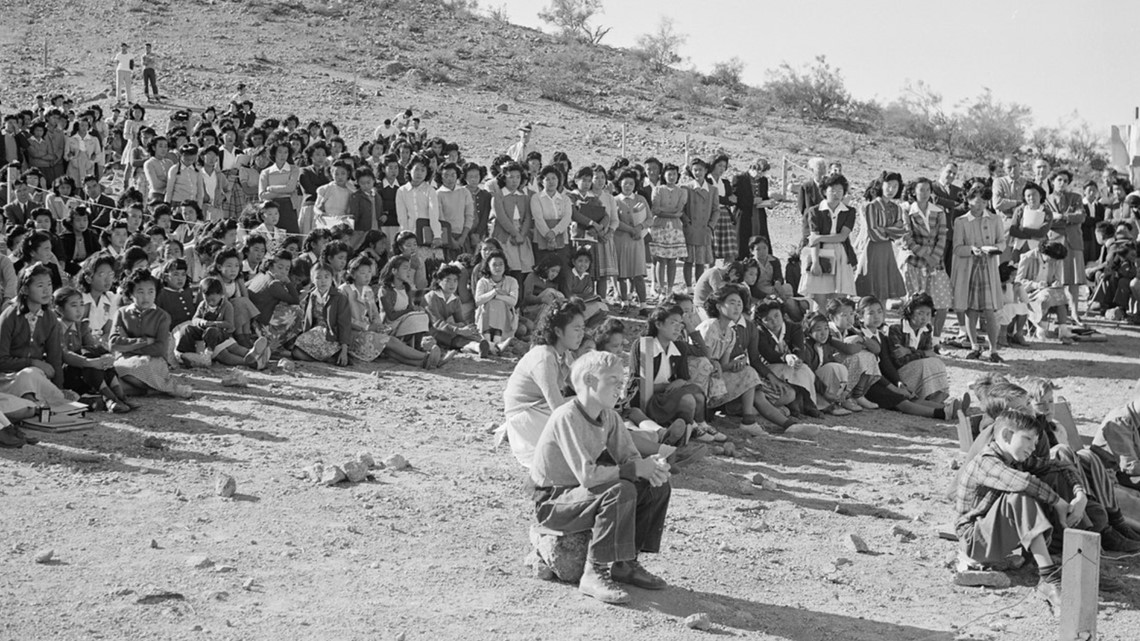

This and another site are reminders that Arizona incarcerated more Japanese-Americans than any other state in the nation during the war.

The barebones area located 50 miles south of Phoenix in the Gila River Indian Community was where the Gila River War Relocation Center was located. Another camp called the Poston War Relocation Center was nearly 200 miles west of Phoenix and was located inside the Colorado River Indian Reservation.

They were two of the largest incarceration camps in the nation. Poston held nearly 18,000 Japanese-Americans and Gila River held more than 13,000, according to the National Park Service.

Feb. 19 marked the 80th anniversary of President Franklin Roosevelt's signing of Executive Order 9066, an order that paved the way for United States military police to force more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans from their homes to be relocated to other parts of the nation.

To commemorate the anniversary, 12 News took a look into the history of each of the infamous sites. Here's what we found:

Gila River War Relocation Center

The center at Gila River was opened on July 20, 1945, despite objections by the Gila River Indian tribe due to the area being considered sacred land.

The camp housed mainly Japanese-Americans who were forced from their homes in California, specifically near the areas of Fresno, Tulare, Turlock and Stockton, NPS said on its website.

"When we first got there...all we knew that it was a desert," Yoshimi Matsuura, a man who was forced from his home and placed to the Gila River site, told Densho Encyclopedia. "But Gila River, it was... I suppose, a shock. Barracks half-finished."

The incarcerees built many of the buildings on the camp, including staff apartments, refrigerated warehouses and a water filtration plant, the park service said. The WRC also saw multiple problems caused by poor infrastructure and the harsh desert environment.

Japanese-Americans forced to live at the center were plagued with chronic water shortages, often running out of water by nightfall, and had to build their own swamp coolers with random scraps of lumber to get relief from the extreme heat.

"A lot of [the incarcerees] went around trying to pilfer pieces of lumber to build things, but that was because they had lumber scraps here and there...and build a swamp cooler," Alfred 'Al' Miyagishima, another man moved to Gila River told Densho.

"You'd make a big hole on the side of the barrack to allow this fan to sit there," Yasu Koyamatsu Momii, another Gila River incarceree told Densho. "It was, like, so sticky. It was humid. Oh, if you sat in front of it you'd be, just get so sticky."

The camp had a formal self-governing system run by a council of representatives from each of the living blocks, Densho said on its website. The representatives were usually Issei, or first-generation Japanese immigrants.

Members of the War Relocation Authority administrators were not comfortable working with Issei due to a fear they might have been more "pro-Japanese." Instead, they wanted to work with Nisei, or the children of first-generation Japanese immigrants. The refusal to work with the community's elders caused tensions to rise in the camps.

Japanese-Americans of all ages worked the camp's vegetable fields, livestock pens, and cotton and alfalfa crops, according to the park service. The food produced by those forced to live at the camp made up for twenty percent of all the food used at camps across the country.

The incarcerated people at the Gila River Wcamp did what they could to find happiness in spite of the poor living conditions, according to NPS. Planting gardens, building fishing ponds and taking care of trees for shade were some of the pastimes the Japanese-Americans were allowed to take part in.

The camp was eventually closed on Nov. 10, 1945. The last to be allowed to leave were 155 Japanese-Americans from Hawaii.

Poston War Relocation Center

The War Relocation Center at Poston opened on June 2, 1942 and was also placed on a Native American reservation, this time the Colorado River Indian Reservation.

The reservation also opposed the use of their land for the center, but the tribe was overruled by the Office of Indian Affairs, today known as the Bureau of Indian Affairs, NPS said. Poston became unique among the other relocation centers as it was primarily run and overseen by the Office of Indian Affairs.

The incarcerees were "on a reservation within a reservation," one member of the Colorado River Indian Tribes told the Poston Community Alliance.

Conditions at Poston weren't much better than at Gila River when it came to the extreme weather and poor living conditions, according to the park service. The living areas were makeshift and weren't insulated, meaning they were extremely hot during the summers and extremely cold during the winters.

"People were fainting like flies, because none of us prepared for any of this," Rudy Tokiwa, a Japanese-American forced to leave his home and move to Poston, told Densho. "All you got is a barrack, and it's hot as hell in the barracks."

"Rattlesnakes were all over the place," Ruth Y. Okimoto, another incarceree at Poston, told Densho. "Saw a lot of scorpions...I was so fascinated with it...I scooped up a scorpion and...I put that scorpion bottle right next to my cot. That was my pet, we weren't allowed pets in camp."

The Japanese-Americans at Poston were also used as laborers to build schools, practice experimental farming and create irrigation systems, according to the Poston Community Alliance. The work that the incarcerees completed was reportedly instrumental in making the area more livable.

Tensions and resistance were strong at Poston, Densho's website said. Distrust among Issei was present here as well and officials only allowed Nisei to serve on the community council. Japanese-Americans at the camp created an unsanctioned "Issei Advisory Board" to make sure the group was represented.

Attacks on individuals suspected to be U.S. Office of Indian Affairs informers also happened at Poston, Densho said. An attack on an alleged informer led to the administration holding two men without charges. Incarcerees responded by organizing a general strike until the administration released the prisoners.

The Poston camp closed on Nov. 28, 1945, and many of the incarcerees returned to the west coast to rebuild their lives while others resettled elsewhere, Poston Community Alliance said.