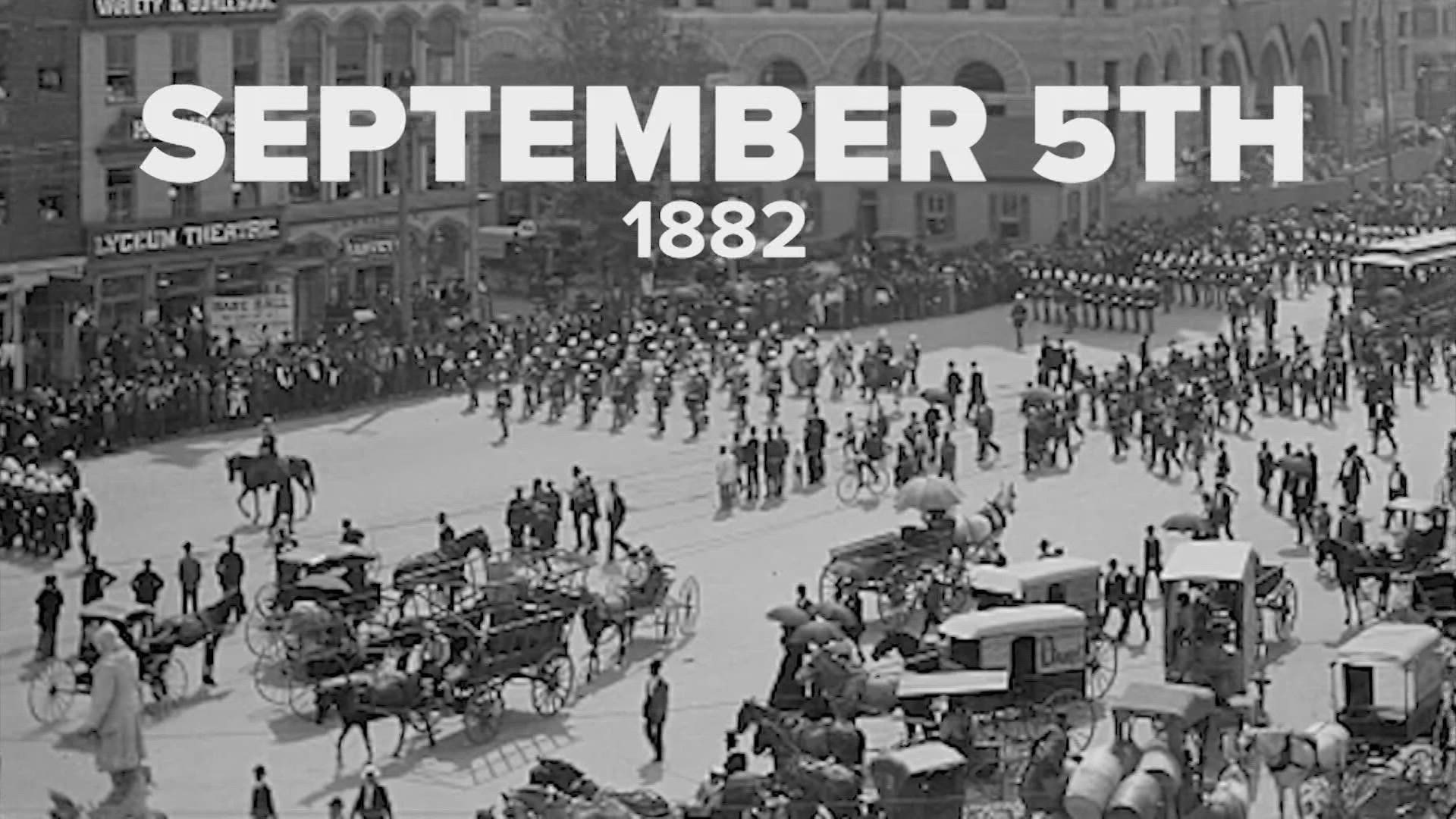

BISBEE, Ariz. — Labor Day has been marked with pool parties, barbecues and parades in modern times. However, the holiday's origins are tied deeply to the labor rights movement throughout the United States.

The nation's workforce no longer has 12-hour workdays and workers no longer have to face dangerous working conditions thanks to the demonstrations of labor unions going back as far as the 1880s.

Arizona saw its own fair share of history-defining moments in the nation's labor history, happening even before Arizona was named a state. The first strikes were formed by miners in Tombstone and Globe in the late 1800s.

The most infamous moment in Arizona's labor history, however, happened in the southern town of Bisbee in 1917, when around 1,500 deputies arrested more than 1,200 men during a strike, loaded them onto train cars without a trial, and left them in the desert in New Mexico.

How the strike began

World War I caused a spike in the demand for copper nationwide, according to archives from the University of Arizona Libraries. This huge demand turned Bisbee's Copper Queen Mine into a 24/7 operation, with miners working harder and longer shifts for often the same pay.

The extremely dangerous conditions miners were forced to work in can be seen in a Department of The Interior document titled "Elementary First Aid for the Miner." The document acted as a resource for miners to care for the bleeding of multiple wounds, how to dress multiple broken bones, and how to treat multiple burns.

"In most mine accidents a miner is injured at or near the working face where no first-aid supplies are at hand," the document said.

"It is the aim of this book to tell the miner how to use brattice cloth, pieces of board, broken ties, bark off of props or posts, rope, wire, coats, jumpers, etc., as aids in dressing the wounds of the injured man."

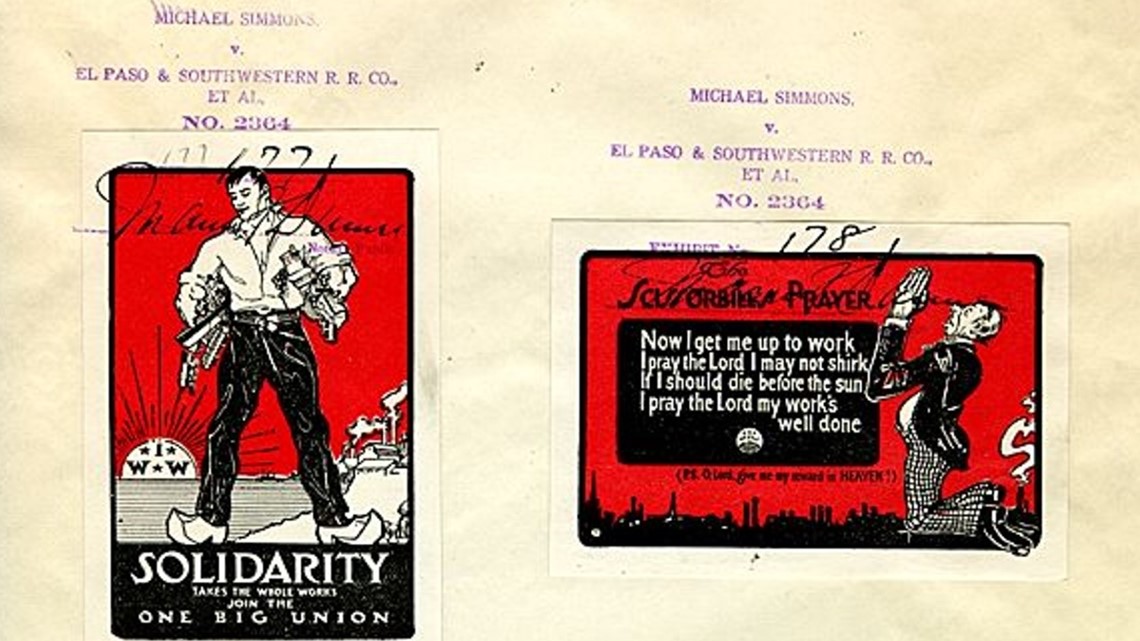

In light of the dangerous conditions and low wages, the Industrial Workers of the World, an international labor union, organized more than 5,000 workers to strike in Bisbee, Mayer, Jerome and other cities, according to the Arizona Historical Society.

The miners in Bisbee listed seven demands to the mine owners according to a Bisbee Daily Review newspaper article from June 27, 1917, including:

- The abolition of the physical examination

- Two men to work on machines

- Two men to work together in all areas

- To discontinue all blasting during shaft work

- The abolition of all bonus and contract work

- To abolish the sliding scale. All man under ground a minimum flat rate of $6.00 per shift. Top men $5.50 per shift.

- No discrimination to be shown against members of any organization.

The mining owners, and the Cochise County Sheriff's Department, did not agree to these demands.

Deputies begin deportation of the striking miners

Cochise County's sheriff at the time, Harry Wheeler, posted a statement in the Bisbee Daily Review on the morning of the deportation, saying that he had created a posse of 1,200 men and asked for others to join him in arresting the "strange men" who were asking for better working conditions.

"I, therefore, call upon all loyal Americans to aid me in peaceably arresting these disturbers of our national and local peace," Wheeler said. "I am determined if resistance is made, it shall be quickly and effectively overcome."

The members of the sheriff's posse, which eventually totaled 1,500, wore white armbands to distinguish themselves from those they were going to arrest, according to the Arizona Memory Project. The posse then rounded up 1,200 men, marched them down to the nearby baseball fields, and loaded them onto train cars to be deported out of the state into New Mexico.

Fred Watson, one of the deportees, later gave an account of the deportation, saying that he didn't have access to food or water for the majority of the train ride and his train car was covered in sheep dung.

"After nearly fifteen hours of travel and no water, the deportees were abandoned in the middle of the New Mexico desert with only the clothes on their backs," the Arizona Geographic Alliance said.

The aftermath of the deportation

The deportees were free to leave the camp set up for them by New Mexico's state government at any time, but few ever returned to Bisbee as the sheriff made it next to impossible for any of the deportees to reenter, according to the geographic alliance.

"Hundreds of unknown adult men within the city limits were tried by a secret court, and most of the men were deported and threatened with lynching if they returned," the alliance's website said.

"Even long-time citizens of Bisbee were deported by this 'court.' Citizens were required to have a “passport” to exit or enter Bisbee."

Upon hearing of the deportation, President Woodrow Wilson set up the Federal Mediation Commission to investigate the events. The findings were documented in the Report on the Bisbee Deportations.

"The deportation was wholly illegal and without authority in law, either State or Federal," the report said. "The function of the local judiciary was usurped by a body which to all intents and purposes was a vigilance committee, having no authority whatever in law."

The report asked Arizona Gov. Thomas Campbell to punish the sheriff and the others involved in the deportations.

The sheriff and his posse of vigilantes were never convicted of any crime.

I-Team Investigates

See award-winning journalism and fact-checking from the 12 News investigation team on our 12 News YouTube playlist here.