ARIZONA, USA — The United States left Afghanistan after 20 years and commentators said it was the longest armed conflict in American history. But they were wrong. That happened in Arizona and throughout the Southwest.

The conflict was called the Apache Wars.

What the Apaches Wars were – and the conflict's effects – can still be seen throughout Arizona today.

What were the Apache Wars?

The last U.S. troops left the Kabul airport in August, officially marking the end of the 20-year long Afghanistan War.

The Apache Wars lasted 18 years longer than the war in Afghanistan, from 1848 through 1886. It was a series of campaigns and running conflicts between the U.S. Army and the Apache tribes.

Some sources even argue that the conflict lasted for a total of 74 years through minor conflicts.

How did the Apache Wars start?

Apache Chief Mangas Coloradas had established a treaty with the United States government in 1848 after Mexico's defeat in the Mexican-American war. The treaty laid out a designated area of land for the Apaches that was independent of the United States government.

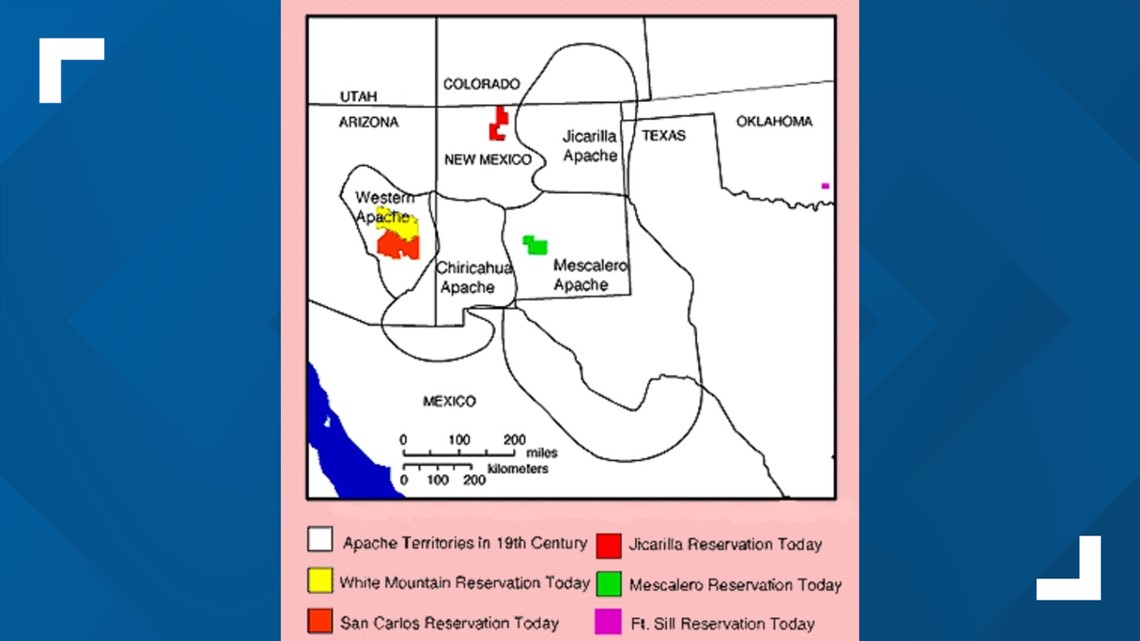

That land was in areas that now make up parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and Mexico.

"In that treaty, we didn't turn over a spoonful of dirt to the United States," said Leland Michael Darrow, tribe historian of the Fort Sill Apache Tribe in Oklahoma. "We gave them permission to build forts and trading posts in our territory and cross through our territory. That was basically what the concessions from our side were."

That peace treaty was soon ignored by Americans after the discovery of gold and silver in the areas, Darrow said. The conflicts this would cause would eventually result in countless lives lost and the reduction of Apache land to a fraction of what they lived on before.

The Apaches lived in an area referred to by historians as "Apacheria" and it stretched from central Arizona to as far as southern Colorado and the Texas-Mexico border. Apache tribes had been at war with Spanish and Mexican armies for centuries as they repeatedly invaded Apache lands from the south and the Apaches would raid Mexican farms in Sonora.

In the years after the Apache-U.S. treaty was signed, the tribes also had to worry about settlers from the United States illegally moving into Apache land.

The United States settlers illegally moving onto Apache land-based the legality of their settlement on the 1493 "Doctrine of Discovery," a proclamation made by Pope Alexander VI that said any land inhabited by "non-Christians" could be claimed and exploited by Christians.

The first notable physically violent incident happened near a New Mexico mining camp in 1848, not long after the treaty was signed. Chief Coloradas attempted to convince miners to move further southward out of Apache lands. The miners responded by tying Coloradas to a tree and whipping him nearly to death.

Coloradas retaliated by gathering his forces and driving the miners out of the region.

"From our perspective, we still owned the land and still had rights to the land," Darrow said. "These ... were invaders. It was basically an invasion and exploitation of our territory. It was done with the active support of the United States military."

He went on to say the U.S. government facilitated this exploitation by trying to move all of the Apaches away from "all these good, taxpaying citizens" who were looking to set up farms and mines on Apache land.

"The United States then engaged in what these days would easily be recognized as an ethnic cleansing program," Darrow said.

What happened in Arizona during the Apache Wars?

The conflicts in Arizona during the Apache War solidified the American Southwest as the last great frontier in the U.S., according to University of Arizona anthropologist Thomas Sheridan.

"A frontier is a place where no one group, whether it's an empire, tribe or nation, has a monopoly on violence, and that characterized this region," Sheridan said.

Two of the most renowned events of the Apache Wars' violence took place in Arizona: The Bascom Affair and the Battle of Apache Pass.

The Bascom Affair is historically remembered as a misunderstanding around a kidnapping that led to 11 years of conflict, according to the National Parks Service.

It began after two Apache groups raided the ranch of a man named John Ward near Arizona's Fort Buchanan. The raid resulted in the kidnapping of Ward's 12-year old stepson named Felix.

The raid was blamed on the Chiricahua Apaches, even though this specific tribe was more than 100 miles away from the site of the raid, the park service says on its website.

Lt. George Bascom and 54 men of the 7th Infantry traveled from Fort Buchanan to the aptly named Apache Pass to demand the boy be returned. When they arrived, the Apaches denied any participation in the raid and offered to help find the boy.

The Chiricahua Apaches at this time were led by Cochise, son-in-law to Mangas Coloradas and later the namesake of Cochise County.

Lt. Bascom refused the Apaches' offer and told Cochise to have his brother, Coyunturo, search instead, park service documents say. Before Bascom could imprison Cochise, the chief escaped the encampment and left the rest of his party with the infantry.

Cochise's party members were then held as hostages by Lt. Bascom, who refused to release them until Cochise gave him the kidnapped boy. Cochise and the Apaches responded by taking their own hostages from a wagon train going through Apache Pass.

The stalemate continued and resulted in the deaths of multiple soldiers and hostages on both sides, including an estimated three dead Americans, nine dead Mexicans and four dead Apaches.

The kidnapped boy that started this all was raised by Coyotero Apaches and grew up to be named Mickey Free, NPS said. He later became both an Army scout and Apache scout, showing little allegiance to either group.

The Bascom Affair created the violent tensions felt by both U.S. soldiers and Apache peoples near Apache Pass. These tensions culminated in another conflict: the Battle of Apache Pass.

The Battle of Apache Pass involved the Chiricahua Apaches against Union infantry, led by Captain Thomas Roberts, who was moving through the pass to push back Confederate troops to New Mexico.

Cochise could see the troops approaching from far off and prepared his troops for an ambush, situating them behind trees and rocks high above the pass. The Apaches opened fire when the infantry soldiers came within range.

The soldiers retreated to the mouth of the pass and continued to shoot at the Apaches. The soldiers had some added punch with two cannons they had brought with them.

Three U.S. soldiers and 10 Apaches were killed, according to "Records of California men in the war of the rebellion, 1861 to 1867."

Arizona's historic Fort Bowie, now a national historic site outside of Tucson, was erected at Apache Pass in case another battle happened there again.

Why don't more people know about the Apache Wars?

One of the biggest reasons this part of American history is often overlooked is due to Americans' refusal to see the U.S. as the colonial power that it is, Sheridan said.

"When the settlers of the original 13 colonies revolted against the British, they were revolting against a colonial power. That is a big part of our identity," Sheridan said. "As we moved westward, we were conquering hundreds of different Native nations...and then conquering Spanish and Mexican outposts."

Coming to terms with the more brutal parts of history has been an ongoing battle within United States schools.

There have been multiple challenges made to expanding Native American history in U.S. public schools. Texas and multiple other states have put laws into effect mandating how race can be talked about in a classroom setting.

"We don't like to think of ourselves in that way because we associated colonialism and imperialism with Europe," Sheridan said. "But, you know, we really were."

The lack of education also impacts Native American children, the vast majority of which are taught in the public schooling system, according to Darrow. If Native American history isn't given the focus it deserves in the American education system, Native kids will never get to learn their own history.

RELATED: Native American group speaks on importance of representation after appearing on 'World of Dance'

"Most of our tribal members don't have a good grasp on our own history," Darrow said. "We don't have a situation where we have control over the information that is presented. We can only add little bits and pieces where we can."

Darrow has seen Apaches usually framed as fierce warriors or blood-thirsty revenge-seekers in history books. But, that perception isn't backed up by studies from anthropologists or tribal nations.

He wishes the truth of the Apache peoples being a peaceful people who did not enjoy fighting would shine through the brutal perception often given.

"They were not a warrior people...it was not an ingrained part of our culture," Darrow said. "There are tribes that are considered militaristic, war-like tribes...but we didn't have any military societies. We didn't have any awards that we gave people for killing enemies or accomplishments in battle."

Reframing these incorrect beliefs Americans have of Native American tribes could be a good first step to remedy the state of Native history in our country.

"People are so indoctrinated in the standard storytelling version of American history that they don't even bother to question whether there may be other perspectives," Darrow said. "People have these incorrect beliefs so ingrained in their brains that they automatically make the association unconsciously. These are the lingering effects of the ingrained way people think about Native Americans."

VERIFY

Did you miss one of our Verify segments? You can find all of our VERIFY stories on our 12 News YouTube playlist here.