ARIZONA, USA — Monsoon brings rain, dust and heat to the Valley's desert, but another type of temperature also rises during the rainy season.

The severity of what Valley dwellers call "monsoon mugginess" can be measured with wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT), which measures heat stress on humans by combining multiple weather conditions, like dry air temperature, humidity and cloud cover. If WGBT gets too high, the human body can't physically cool itself, resulting in heat-related illnesses and deaths.

This temperature reading has risen during the past two year's monsoon, and has risen each time Arizona doesn't see a so-called "nonsoon."

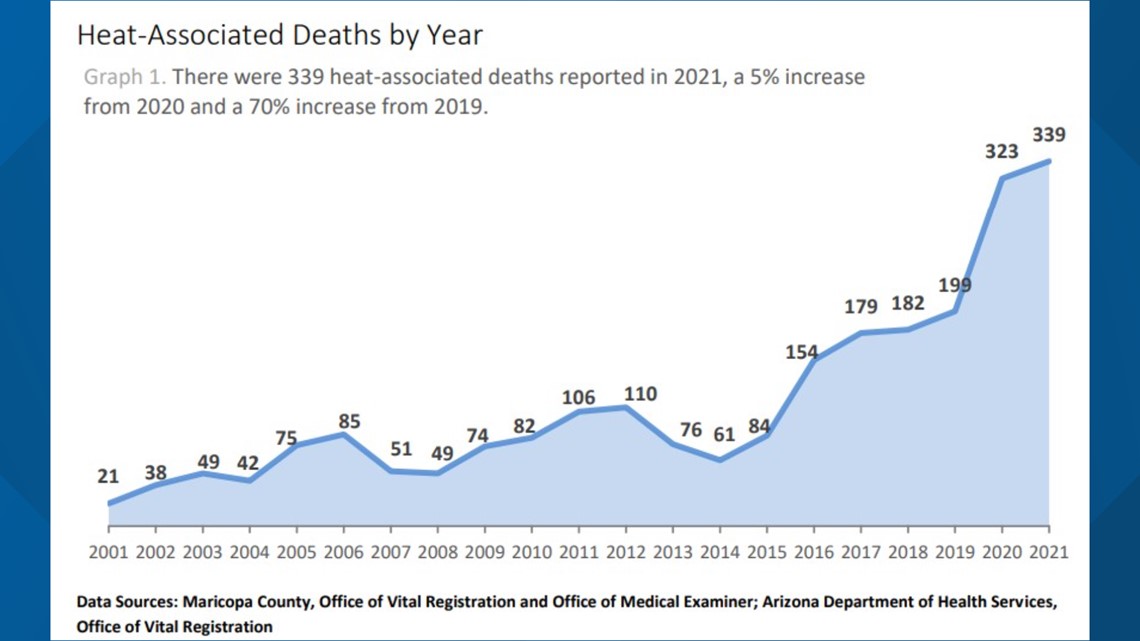

This year and last have also seen record-breaking amounts of people who have died during Arizona's extreme summer heat. Maricopa County saw the highest amount deaths ruled as "heat-associated deaths" during a single-year period in 2021. 2022 is on track to break that record.

Are the recent spikes in Valley heat deaths the result of a rise in monsoon mugginess? We spoke to experts to VERIFY.

The question:

Does a rise in "monsoon mugginess" make Arizona's extreme summer temperatures more lethal?

The sources:

The answer:

No, changes in WBGT aren't the driving cause behind how many people die during Arizona's summers. Research shows an increasingly vulnerable population, including older people and individuals without shelter, is the main cause behind rising heat deaths.

The evidence:

The rise in air temperature, also known as "dry-bulb temperature," has an effect on WBGT, but not as much as increases in humidity, dew point temperature and cloud cover.

These types of increases won't be more common in Arizona any time soon, according to state climatologist Erin Saffell.

"Increasing relative humidity, putting more moisture in some way, is going to make people's bodies feel worse, but research isn't showing any increases in Arizona's humidity," Saffell said.

More people in the Southeastern U.S., in states like Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, are focusing on WBGT given the extremely high levels of heat and humidity during the summer.

Arizona's famous "dry heat," however, makes our WBGT not even come close to these states, even on its most humid of days, Biometeorologist Jennifer Vanos said.

"Monsoon makes it more humid in Arizona, so the wet bulb would be a bit higher, but the wet bulb is still going to be pretty low compared to places like Miami," Vanos said.

"If the human body is able to keep sweating and thermoregulate properly, people generally should be okay. In a place like Phoenix, it's usually a physiological limit that results in people dying or ending up in the hospital due to heat."

How close human bodies are to reaching that physiological limit depends much more on how at-risk a population is rather than how severe weather conditions are, according to an ASU study examining the spike in Maricopa County heat deaths seen in 2016.

Increases in the number of people who are considered "highly vulnerable" have a much clearer tie to increases in heat deaths, even when compared to increases in extreme meteorological conditions.

"Our results indicate that factors other than the weather were predominantly responsible for the surge in heat-associated deaths seen in 2016," the study said.

"Of the many potential risk factors for heat-associated deaths that are tracked by MCDPH, two stood out with disproportionately high representation in 2016 cases: homelessness and age."

The lack of resources provided to Phoenix's growing homeless population, and the record-breaking amount of heat-related deaths in it, is one example of those most vulnerable being the most affected victims.

Disability, illness and other pre-existing conditions, are other factors that decrease a person's heat tolerance, the U.S. Department of Labor's website said.

"The demographic shifts we observed among the decedents in this study may suggest that public health and social interventions for specific highly vulnerable populations are not yet fully understood or effective in our region," the study concluded.

Arizona weather

Drought, wildfires, heat and monsoon storms: Arizona has seen its fair share of severe weather. Learn everything you need to know about the Grand Canyon State's ever-changing forecasts here.