PHOENIX — "You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law."

It's a phrase we're all familiar with, and it's part of what's called, the Miranda warning. Nowadays, police officers are required to read it to a suspect when they make an arrest.

The warning is made up of five statements that lay out the rights and protections one has under the constitution.

- You have the right to remain silent.

- Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law.

- You have the right to an attorney.

- If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you.

- Do you understand the rights I have just read to you? With these rights in mind, do you wish to speak to me?

But police officers weren't always required to read someone their Fifth Amendment rights. That practice came about because of the 1966 U.S. Supreme Court case, Miranda v. Arizona. And that case was decided on today's date, Jun. 13.

Confession without rights

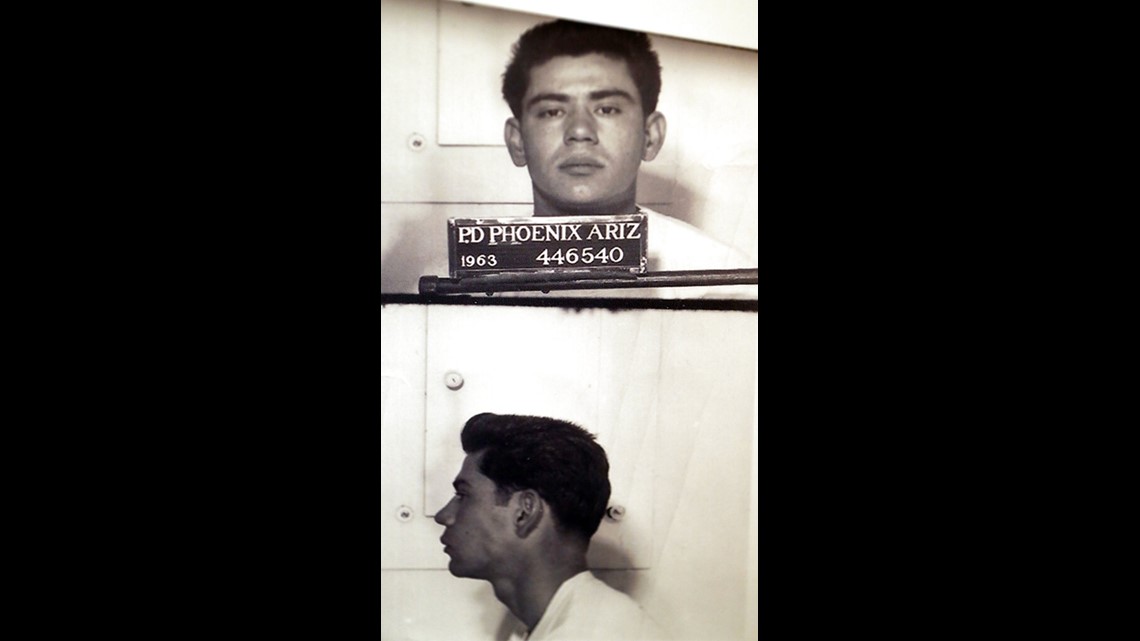

In 1963, Phoenix resident Ernesto Miranda was arrested for kidnapping and sexually assaulting an 18-year-old girl.

While in police custody, officers obtained a written confession from Miranda... But something wasn't right.

During the trial, Miranda and his lawyer protested that he didn't know he could have an attorney present at his interrogation, or that he could choose to say nothing at all.

And it was true. Phoenix police officers admitted that, during the interrogation, they hadn't directly informed Miranda of those rights.

Despite the defense's objections to using the confession as evidence, Miranda was found guilty of the crimes (mostly because of the confession) and sentenced to 20-30 years in prison.

Miranda's conviction was upheld by the Arizona Supreme Court, so in 1965 he submitted a plea for review to the U.S. Supreme Court. The American Civil Liberties Union stepped in to argue his case.

Miranda v. Arizona

Does the Fifth Amendment's protection against self-incrimination extend to the police interrogation of a suspect?

That was the question at the heart of Miranda's hearing before the Supreme Court. The first day of the case started in February of 1966, and arguments ran all the way through June.

Then on Monday, Jun. 13, 1966, the court delivered its opinion: the person in custody must be clearly informed of their rights.

The court was split with a 5-4 ruling. Dissenting opinions argued that this was too strict of an interpretation of the Fifth Amendment, or that it would get in the way of officers being able to do their jobs.

All the same, the Miranda rights are here to stay.

Now the Miranda warning is such a cultural staple that you can find it in almost every T.V. show, book, or movie with police involved. It's hard to imagine, but we wouldn't have those protections if it weren't for this Arizona case.

What happened to Miranda?

After the Supreme Court invalidated Miranda's conviction due to the improper confession, he was retried by the State of Arizona.

At his second trial, the confession wasn't brought up but Miranda was still found guilty on charges of kidnapping and sexual assault.

On Mar. 1, 1967, Miranda was once again sentenced to 20-30 years in prison.

He was paroled in 1972 and died on Jan. 31, 1976, in a fight at a bar in downtown Phoenix. Miranda was buried in the City of Mesa Cemetery.

Arizona Politics

Get the latest Arizona political news on our 12 News YouTube playlist here.