PHOENIX — Indian School Road runs about 40 miles east-west through the Valley. It draws its name from the Phoenix Indian School that once stood where the road crosses Central Avenue.

But what happened at that school more than 100 years ago has remained hidden, covered now with a quiet community park peppered by historic buildings where Native children were once stripped of their identities and forced to assimilate into white America.

"I can't imagine ... in the early days, being taken away from home when you're 5, or 4, and even younger in some cases and being sent away," Patty Talahongva said. "And as a parent, I'm a parent, I would fight tooth and nail to keep my child. And that's what a lot of people did, and they were punished, or their whole tribes were punished."

Talahongva, a Hopi woman who grew up in Northern Arizona, attended the Phoenix Indian School with her sister from 1978-79.

"My grandparents were the first generation to go off to boarding school, and then my parents, and then me ...," Talahongva said. "My son is the first generation boarding-school-free, if you want to call it that, that's crazy when you put it into perspective like that.

Talahongva is the executive producer for Indian Country Today, an outlet that covers news through an Indigenous lens. She's also an adviser in the curation and development of Away From Home: American Indian Boarding School Stories, a permanent exhibit at the Heard Museum in Phoenix.

A majority of the 367 Indian boarding and residential schools in the U.S. have now closed. The schools were modeled after the U.S. military and in the beginning, had the intention of forcing assimilation on tribal nations.

Now, the federal government, spearheaded by the first Indigenous U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, is investigating Indian boarding schools and their troubled pasts after hundreds of bodies of indigenous children, some as young as 3, were found at a residential school in British Columbia, Canada.

"They were modeled after the U.S. federal boarding school policy," Talahongva said about the schools in Canada. "But up there, it was primarily the Catholic Church. All those kids who are found in those graves, the Catholic Church owns that. And they have not said anything about it."

A national nonprofit working to address the ongoing trauma created by the U.S. Indian Boarding School policy reported that by the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Native children were removed from their homes and placed in boarding schools operated by the U.S. federal government and churches.

"We're not taught in any decent fashion about the history of boarding schools. And yet you look at the trauma, our families have survived ... the trauma that these kids went through," she said. "It's not that it's like, ancient history."

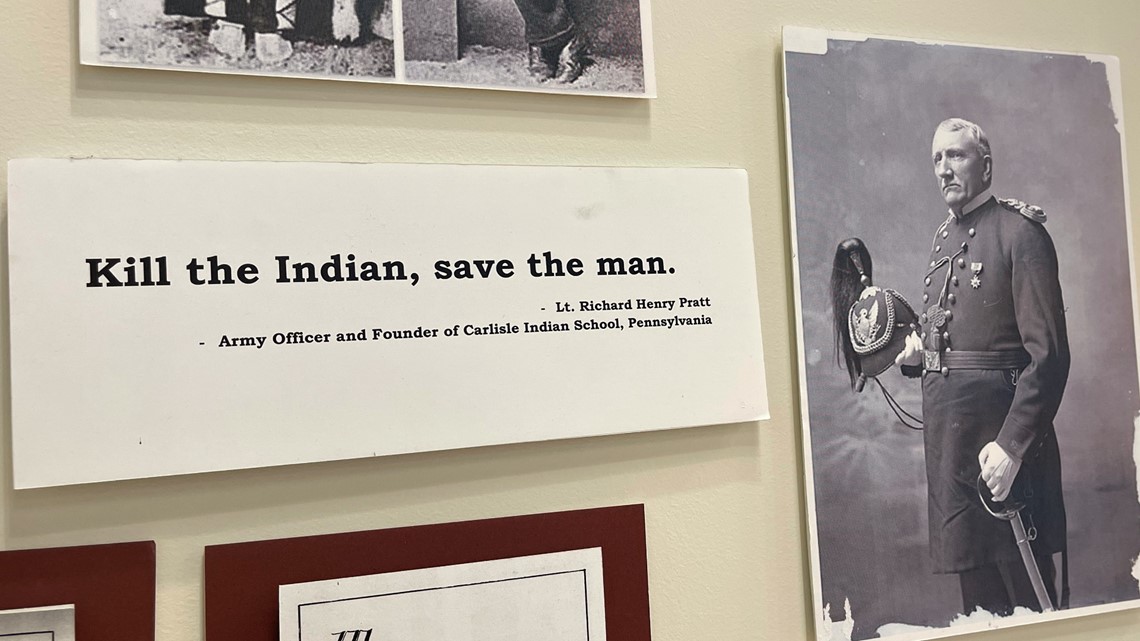

"Kill the Indian, save the man"

The biggest proponent of the school movement was a former Army officer.

"And Henry Pratt, who was an officer in the Army ... he set up the boarding schools like military barracks. And that's why at the beginning of the school, the kids wore uniforms and they marched everywhere. like they were little soldiers."

Pratt's goal? Complete assimilation.

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was the first government-run boarding school for Native American children, opening in 1879. Native children were forced to assimilate into white American society under the belief of “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” a phrase Pratt was known for.

The Phoenix school was similar to Carlisle. Native children were forcibly removed from their homes then brought to the boarding school where the process of stripping away their identity happened immediately: their hair was cut, their clothes were taken and often burned and they were given "white" names.

They could no longer speak their native languages, Talahongva said.

Instead, they were taught to march, to pray, and to speak, read and write English.

Discipline was severe and often meant confinement, “bread and water” meals and corporal punishment.

"But you know what, things have a way of becoming normalized," Talahongva said. "And then you just accept agents are going to come and take our kids away ... In the end, it's like, how do we escape this?"

'Checked out like a book'

Talahongva attended the Phoenix Indian School -- "PI" to its students -- at a time when attitudes toward Natives were improving – but she wasn't shielded from trauma.

"My mother really hated having to send us to the (Phoenix) Indian School," Talahongva said. "She said, 'Boarding schools, they're not good, they don't have a high educational standard.'"

Talahongva said she and her sister had no choice but to attend the boarding school because there was no junior high or high school on their reservation.

"My experience at the boarding school is different. I would say it was both good and bad," she said. "Anytime you're away from your family, it's hard. And honestly, how can one, even a staff of dorm attendants ... really raise you? Nobody's raising you, you're raising each other."

Her stint at PI was toward the end of the school's run, but she said the school was known for sexual assault and molestation, and it still ran rampant.

"It's like a part of the boarding school history," she said. "We all knew, but who do you tell because, clearly, other people knew about it. Other teachers, the administration, and nothing was done with that person."

PI was similar to a trade school when Talahongva attended. Girls learned to cook and clean while the boys did yard work.

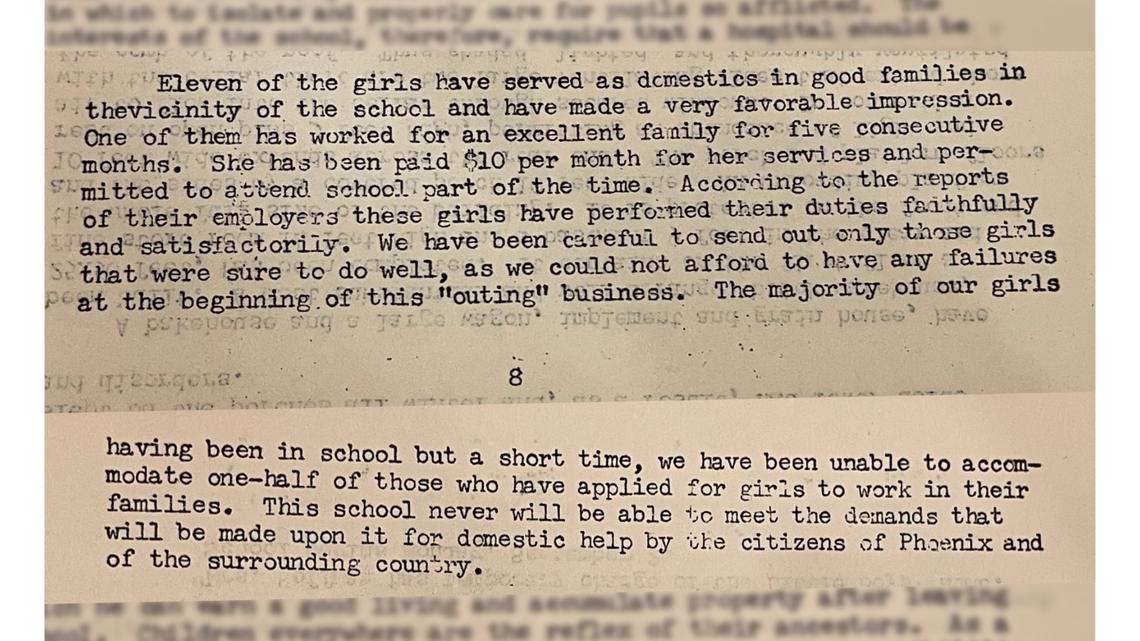

The outing program, Talahongva said, was an opportunity for anyone in the Valley to drive up to the school's dorm on weekends and "check out a student for the day" to complete tasks they had learned in school.

"No one ever had their fingerprints on file, no background check. They didn't even call your parents to say 'hey, somebody is going to pick up Patty today,'" she said. "People (would) get picked up and checked out like a book. There was no oversight in that program."

'Indians are so damn tough'

A group of 21 Democratic lawmakers sent a letter in August to the Indian Health Service asking that the federal agency make available culturally appropriate support services such as a hotline and other mental and spiritual programs as the federal government embarks on its investigation into the schools.

"You know, every time we talk about this history, we're being re-traumatized in some fashion," Talahongva said. "So what's being done to take care of us? What's being done to take care of, you know, the survivors?"

The press secretary for the Interior Department in January told 12 News the department and the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition recently signed a Memorandum of Understanding to share records and information in support of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative

The department added that leaders are working with the Indian Health Service to "develop culturally appropriate support resources for those who might experience trauma resulting from the initiative."

"Take a minute and consider what we've gone through," Talahongva said. "It's a miracle. I'm here, it's a miracle any of us are here. We're still standing, you know. Indians are so damn tough."

Up to Speed

Catch up on the latest news and stories on the 12 News YouTube channel. Subscribe today.