This empty lot in Phoenix could hold one of city's darkest secrets. A federal investigation could tell us more next month

It’s fenced off, full of trash and sits forgotten as the rest of the once-160 acres of the former Indian residential school has found new life.

Dacia Johnson/KPNX

There’s an empty corner lot at the intersection of Central Avenue and Indian School Road in central Phoenix.

It’s fenced off, full of trash and sits forgotten as the rest of the once-160 acres of the former Indian residential school has found new life.

Surrounding much of that empty corner lot is Steele Indian School Park, a community space home to several festivals each year, where volleyball teams play on sand courts to the north, and VA Medical Center visitors find solace in the Entry Garden to the southeast that spirals into a peaceful pond.

But in the sunniest city in America, that empty corner lot on Central and Indian School might be hiding one of Phoenix's darkest secrets: Graves from a time when the land was part of Phoenix Indian School – a place where Native children were stripped of their identities after being torn from their families and tribal land, and taken to live, work and learn how to be White.

The mystery of the corner lot is consistent with the history: No one cared enough to mark it.

Phoenix Indian School was one of more than 350 Indigenous boarding and residential schools in the U.S. – 51 of the facilities were in Arizona.

For the last year, the federal government has been investigating these Indigenous boarding schools after hundreds of bodies of indigenous children, some as young as 3, were found at former residential schools in Canada.

The U.S. investigation was spearheaded by Deb Haaland, the nation's first Native American Secretary of the Interior.

A full report is expected to be complete on April 1.

Chapter 1 Illness, death

Phoenix Indian School opened in 1891 and documents show record-keeping was poor, especially during the first 40 years. A 1933 letter from the U.S. Department of the Interior scolds the school's superintendents and on-site medical staff accusing them of not keeping or retaining records.

But some documents from the National Archives and Records Administration do show outbreaks of illness and death among students at the school.

A 1930 letter to the school from the Department of the Interior questions why the department was receiving reports about Navajo children sent to Phoenix Indian School losing their health, contracting tuberculosis, and "numbers of them dying."

"The government did not send the bodies home. It was too expensive. It was too cumbersome," said Patty Talahongva, a Hopi woman who attended Phoenix Indian School with her sister from 1978-79. "For 99 years, this school existed, yet, they don't have a record of a graveyard. Where did these kids get buried?"

Talahongva is the executive producer for Indian Country Today, an adviser who helped in the curation and development of Away From Home: American Indian Boarding School Stories, a permanent exhibit at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, and was previously the curator at the Phoenix Indian School Visitor Center.

"There was a polio outbreak where those kids died," Talahongva told 12 News. "The Heard [Museum] has letters from, you know, school officials saying 'Dear Mom and Dad, your son died. We buried him in a good Christian funeral.'"

To put it in perspective, Talahongva explained, Phoenix Indian School was modeled after Carlisle Indian School, the first Indian boarding school that opened in Pennsylvania.

"And they have a marked gravesite there," she said. "Carlisle was open for maybe 30 years? Phoenix Indian School was open for 99 years."

At least 180 students died while attending Carlisle.

Chapter 2 Unmarked graves?

Laurene Montero, City of Phoenix archaeologist, said there doesn’t appear to be any direct evidence of a cemetery at the former Phoenix Indian School property.

"To my knowledge, there haven’t been any tribal claims of relatives or ancestors having been interred at the school," Montero said.

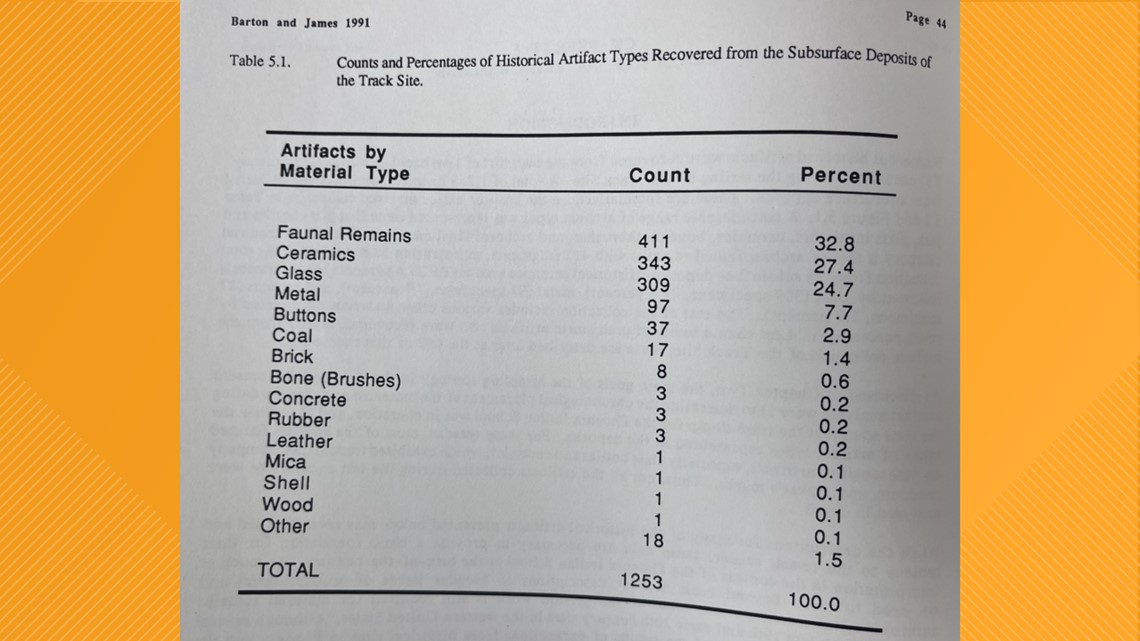

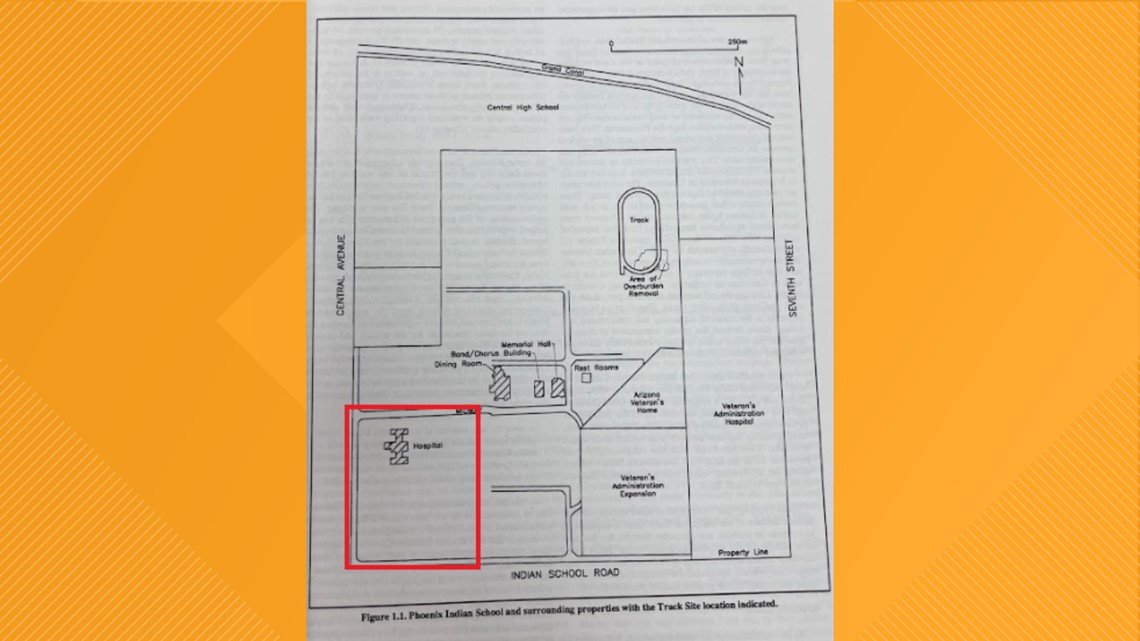

Studies done by Arizona State University in the early-1990s explored an area near the northeast corner of the school property – opposite of the empty corner lot – where a track and possible trash pit were located. Researchers located dozens of historical items from the school grounds -- but no graves.

But Talahongva feels otherwise, suggesting that the empty corner lot where the original Phoenix Indian hospital was located could contain unmarked graves.

The 15-acre corner lot was sold after the school shuttered in 1990.

A nonprofit organization planted a community garden on the lot in 2012 on a temporary lease from Barron Collier who had bought the property to develop.

"I helped, we planted there," Talahongva said, adding that gardeners would ask questions about the project and wanted to know about her experience at Phoenix Indian School.

"And they were telling me all these stories about, 'Oh, yeah, we're not supposed to dig deeper. And then they showed me little blue cobalt medicine bottles they'd found in the ground," she said. "But in my mind, I'm thinking ... they're probably convenient locations to bury, you've got the hospital right there."

The garden abruptly closed in 2017.

The fenced-off property is now owned by the private entrepreneurial investment firm The Pivotal Group. Richard Garner, the firm's chief operating officer, gave the following statement to 12 News:

"We own a small portion of the land that was once the location of the old Phoenix Indian School. While our parcel is but a slice of the original school site and highly unlikely to have any issues, we applaud the City of Phoenix for wisely requiring all developers to be archeologically conscious, including halting development if any archaeological materials or human remains are encountered at any time during construction. We actively support these thoughtful and proactive policies that speak to the city's progressive approach to land-use. The State of Arizona is also to be applauded for its laws regarding culturally sensitive materials discovered during construction. Recently, United States Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American to hold that office, is providing additional and needed guidance to address this important issue with regard to Indian boarding schools and their often troubled history. In this case it is gratifying to see both the City of Phoenix and State of Arizona being ahead of the federal government, largely because of our broader community's deep history, respect and reverence for the area's Native American heritage."

Chapter 3 What's next?

Montero said she's not aware of any communication between the Department of the Interior and the City about Phoenix Indian School and the federal investigation

However, she said she's been in contact with surrounding tribes including Salt River, Pima-Maricopa and Gila River Indian Community Tribal Historic Preservation Offices

"The representatives I met with are not aware of any indigenous claims of ancestral burials at the Phoenix Indian School," she said. "They agree that City of Phoenix should wait to see what the federal government will do rather than pursue a more intensive investigation."

Some organizations across the U.S. are starting to investigate the history of boarding schools and the possibility of remains being found at any of them.

Fort Lewis College in Colorado is considering its own search for remains because it was once a boarding school, and In Utah, a state university plans to apply ground-penetrating radar to a 150-acre site where the bodies of Paiute children are likely buried.

At the University of Minnesota- Morris, a Native student collected more than 30,000 signatures urging the university to search for graves after learning one of the school's buildings was part of an Indigenous residential school.

For Talahongva, the federal investigation can't come soon enough.

"It's about damn time," she said. "A year is not enough time, I don't know what the goal is ... there have been no consequences for people who were so brutal in these boarding schools."

Montero said she hopes to see a plan and funding from the federal government for more intensive research into the school records, photographs and oral testimonies from any students still living.

"There is very little information available from the early time periods," Montero said. "Still, as an archaeologist, I think the absence of evidence is not enough to say there wasn’t a cemetery on the school grounds."

Up to Speed

Catch up on the latest news and stories on the 12 News YouTube channel. Subscribe today.