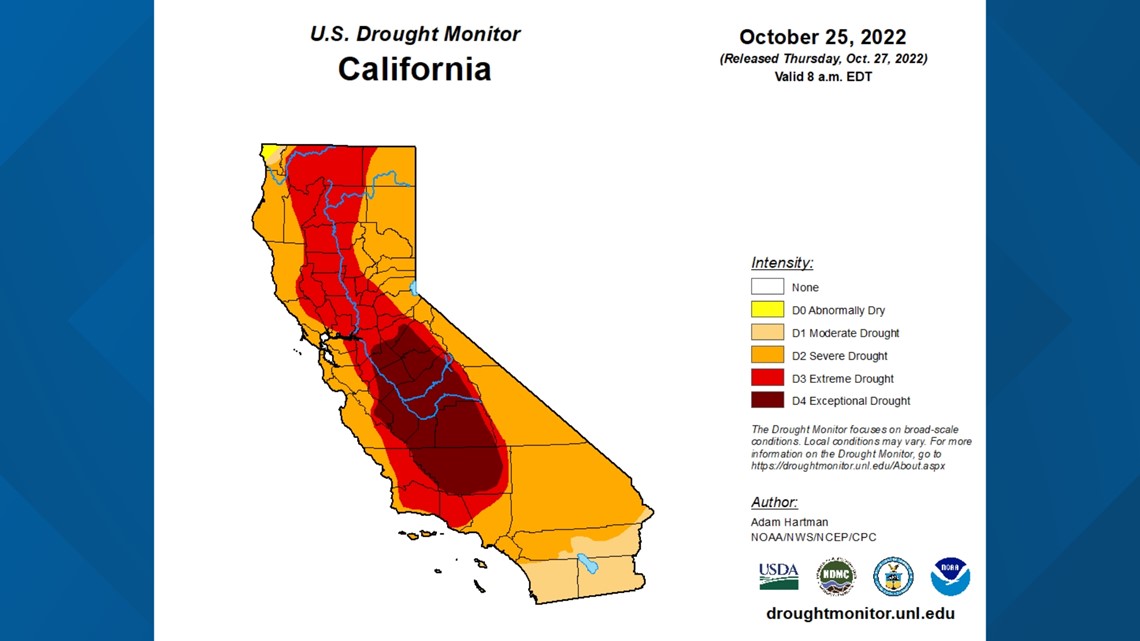

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — Drought has been the headlining story for the West in the last decade, prompting increased worry about the future of water. The latest drought monitor remains relatively unchanged in California, with the worst of the drought still being experienced in the San Joaquin Valley.

While drought is worst in the West, 82% of the United States is currently in some level of drought - the highest percent since the inception of the drought monitor in 1999, according to the latest drought monitor.

The first month of the water year has been dry for northern California, but it appears a pattern shift could be on the way bringing beneficial rain and snow to the region.

Cloud Seeding

As the climate crisis worsens and water issues mount by the year, the topic of cloud seeding is on the mind of many. Some argue cloud seeding is the missing puzzle piece in solving water issues, while others argue “playing God” with the atmosphere will only cause more problems to arise.

The process of cloud seeding is complex and some see it as a one-off fix for the water crisis in the West, but could it really be that simple?

Clouds are composed of minute water droplets which form precipitation when the drops become big enough to overcome gravity. All droplets form around some sort of aerosol, which includes dust, pollen, sand, or other microscopic particles.

Cloud seeding involves sending particles into a cloud to squeeze out precipitation in clouds that would not naturally precipitate, according to Katja Friedrich, professor at the University of Colorado in the department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences. This particle is usually silver iodide, discovered to resemble the structure of ice crystals by Atmospheric Scientist Bernard Vonnegut, brother of author Kurt.

Certain meteorological conditions are required to cloud seed. Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD), who has been cloud seeding since 1968, described a "perfect storm" as necessary to cloud seed, involving the presence of an existing cold, dry Pacific system, according to Lindsay VanLaningham, spokesperson for the power provider.

Cloud seeding has a wild history, a history that has sowed much of the distrust of cloud seeding as a science. In 1918, a man by the name of Charles Hatfield came to California claiming to have the ability to produce rain using a secret mix of chemicals. His methods ran on the principle of "no rain, no pay", according to the 1918 Monthly Weather Review by the Weather Bureau, now known as the National Weather Service. Hatsfield's rainmaking services were wildly popular throughout the West.

While it is possible Hatfield understood the science behind rainmaking, his successes were more likely due to good forecasting ability rather than his secret chemical mix. There are countless other stories of pseudoscientists claiming to possess the ability to make rain fall from the sky.

Modern rainmaking can trace its roots back to 1946. Since then; scientists, governments and even militaries have been studying the effectiveness of cloud seeding to mixed results.

SNOWIE

Cloud seeding research has accelerated in recent years, due in part to the SNOWIE (Seeded and Natural Orographic Wintertime Clouds: The Idaho Experiment) experiment, led by Friedrich.

The three-month long study in the mountains of Idaho involved flying planes attached with silver iodide flares into clouds, targeting orographic clouds -- clouds forced upwards by elevation that wouldn't otherwise precipitate.

"Orographic clouds have these tiny supercooled liquid which is tiny cloud droplets that are below sub freezing and they're too small to lie to really fall onto the ground, so they're basically just hovering the atmosphere," said Friedrich.

This is where the silver iodide comes in. The planes, armed with flares, fly through the slow-moving clouds, injecting them with silver iodide. The silver iodide, which only works at temperatures from -5 to -10 degrees Celsius, attracts droplets that become heavy enough to overcome gravity and fall as snow.

"When we were cloud seeding, we had supercooled liquid clouds, but they were not precipitating. Then, as we were flying to those clouds and putting the silver iodide in there, they started to snow or to produce precipitation that was then measured at the surface. That was pretty revolutionary," Friedrich said.

Incredible advancements in weather modeling over the past 10 years have made cloud seeding research much more feasible, according to Dr. Friedrich.

"I'd say 10 years, our numerical modeling capability actually really improved. We can now simulate clouds much better. We can also simulate the process of cloud seeding, and that really helps because once you modify a cloud in the atmosphere, you never know how much precipitation you would have gotten out of this cloud," Friedrich said.

The study was even more successful than researchers had hoped for. 24 minutes of cloud seeding produced up to 275 acre feet of water (1 acre foot is equivalent to approximately 325,000 gallons).

The silver iodide dispersed in the atmosphere falls to the ground with the precipitation, satisfying EPA thresholds. Friedrich explained that cloud seeding is a controlled experiment.

"We're going out, we're seeding one hour, and then we're producing the snow and maybe two or three hours, and then it's done. So it's not something that is lingering in the atmosphere for years and modifies the weather," Friedrich said.

Cloud Seeding in California

There are many misconceptions surrounding cloud seeding. For one, it has been practiced here in California since the mid-20th century, shocking to many who view geoengineering as a futuristic concept. SMUD, local power provider, has been cloud seeding the Upper American River Project area, which starts at Loon Lake and flows downstream, since 1968 – not for the reason you may think, however.

“We're looking for snowpack that can melt later into the summer months and feed our reservoirs for hydroelectric power generation, so we're not really doing it to solve the drought, which is what a lot of people think,” said VanLaningham.

According to VanLaningham, cloud seeded areas have experienced a 3-10% increase in snowpack. For every inch of snowpack generated for hydroelectric reasons, SMUD customers save $1 million, which is a good return considering SMUD's budget for the practice is $1.5 million over five years.

While it is undeniable cloud seeding works on a small scale as seen by the SNOWIE study and SMUD's decades of cloud seeding use, cloud seeding isn't the magical solution solving drought issues in California. Although cloud seeding isn't enough to solve drought currently, technology will continue to advance and it could make more of an impact in the future. There are obvious benefits to continue the practice, and in the end, every drop of water matters in an uncertain future.

WATCH ALSO: