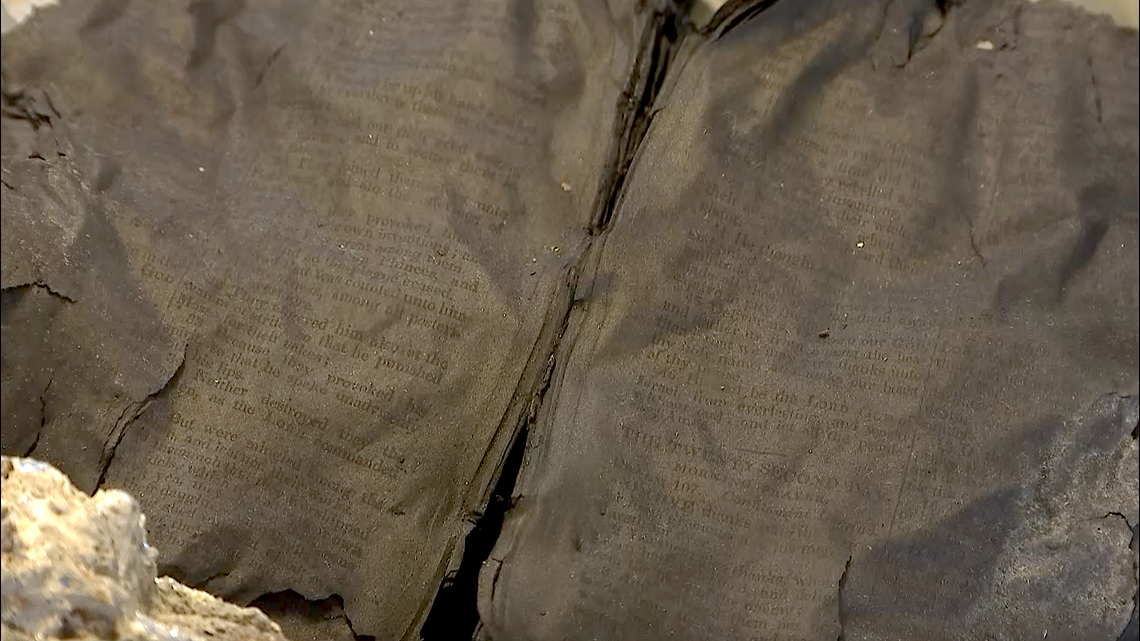

When the smoke cleared, little was left intact. It was almost as if a town had never even existed there. Some broken China and a tabernacle survived the inferno. So did a Bible. The Good Book was charred by the flames and petrified by the intense heat, but found intact -- and opened to Psalms 106 and 107.

"Oh give thanks to the Lord, for he is good, for his steadfast love endures forever!" the beginning of Psalm 106 and 107 reads, a haunting declaration that may seem to contradict the tragedy that unfolded one fateful night in northeastern Wisconsin but serves as a reminder of a dark chapter in American history almost 150 years ago, the country's deadliest fire.

On the night of Oct. 8, 1871, a rapidly approaching fire engulfed the small town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin, a lumber boomtown in America's dairyland. The blaze tore through the town at an astonishing pace, spreading hellish flames and plumes of thick smoke. According to historical accounts, horrific sounds filled the air under an ominous orange sky that night as chaos ensued.

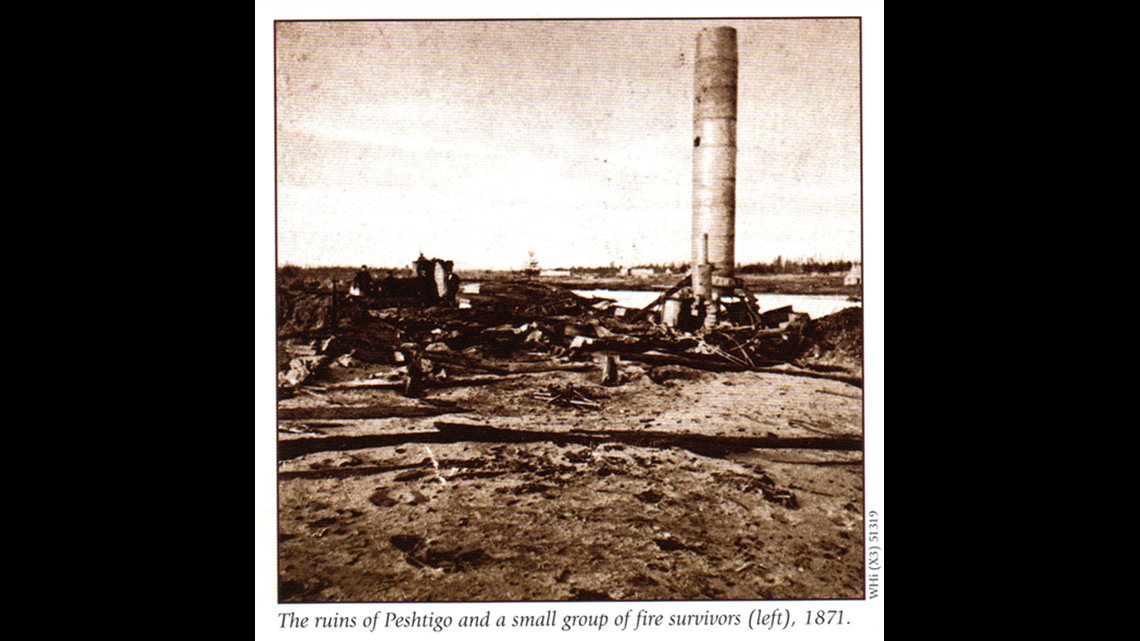

In the span of about one hour, the fire incinerated anything and everything in its path, including numerous settlements and villages, ravaging 2,400 square miles -- an area roughly the size of Delaware.

The story of Peshtigo is a lesser-known one, however, as it occurred the same night of the Great Chicago Fire, a disaster that overshadowed what happened in Peshtigo, 250 miles due north of the Second City. In fact, over a 48-hour period beginning on Oct. 8, a series of wildfires swept across portions of Illinois, Wisconsin and Michigan and they collectively remain among the worst disasters in American history.

AccuWeather National Reporter Blake Naftel recently traveled to the Great Lakes region and interviewed Sally Kahl, the curator for the Peshtigo Fire Museum.

"You can't work at this museum and not feel the pain that these people must have gone through," Kahl, a lifelong Peshtigo resident, told Naftel. "I can't."

Kahl became almost overwhelmed with emotion as she talked with Naftel and gestured toward some of the exhibits in the museum -- glass cases that hold the charred bible, plates and a pristine tabernacle that was found in a river, some of the few artifacts that were recovered after the inferno.

Forweeks smoke from ongoing fires to the west cast a grey haze into the atmosphere,suggesting that dangerous fire weather and extensive grass fires were alreadyoccurring upstream of the region in the Plains.

Only two weeks before the Peshtigo inferno, another fire had encircled the town but was extinguished before it did serious harm.

"The residents got [the fire] out and everybody celebrated," Kahl said, adding that a sense of hubris had set in after the townsfolk averted that would-be disaster.

Residents were aware of a looming threat, but no one was prepared for what that terrible October evening would bring. The fires began north of Green Bay and surged northeastward.

"All of a sudden they noticed the sky is not grey anymore. It's orange and red. They knew something was coming. Then the wind started and they heard an awful noise like a train was coming," Kahl said.

As the firestorm charged through the town, residents only had one place to take refuge, so they fled into the Peshtigo River. In October, the water temperature of Peshtigo River is usually between 50 to 60 degrees. In water of that temperature, it only takes 10 to 15 minutes for humans to lose the ability to use their hands.

"[The fire] snapped off the top of trees and the trees kind of exploded. About an hour and Peshtigo was gone. There was nothing left," Kahl said of the aftermath.

A local town minister, Reverend Peter Pernin, wrote an eyewitness account of what it was like to live through and survive the horror of that night:

"The air was no longer fit to breathe, full as it was of sand, dust, ashes, cinders, sparks, smoke, and fire. It was almost impossible to keep one's eyes unclosed, to distinguish the road, or to recognize people, though the way was crowded with pedestrians, as well as vehicles crossing and crashing against each other in the general flight. Some were hastening toward the river, others from it, whilst all were struggling alike in the grasp of the hurricane. A thousand discordant deafening noises rose on the air together. The neighing of horses, falling of chimneys, crashing of uprooted trees, roaring and whistling of the wind, crackling of fire as it ran with lightning-like rapidity from house to house-all sounds were there save that of human voice. People seemed stricken dumb by terror. They jostled each other without exchanging look, word, or counsel. The silence of the tomb reigned among the living; nature alone lifted up its voice and spoke."

Word of the fire did not reach government officials in Wisconsin's capital for days, Kahl said. However, help finally began making its way to those in need when Francis Fairchild, the wife of Wisconsin governor Lucius Fairchild, received word of the tragedy.

The blazes were a wake-up call about the land-use practices of the time as communities searched for answers in the wake of the tragedy. Slash-and-burn lumbering, construction from the expanding railroads and daily use of flame all contributed to the cause of the fires that proved so destructive. But the weather in the months leading up to the blaze also played a crucial factor in creating dangerous conditions that allowed for the disastrous outcome.

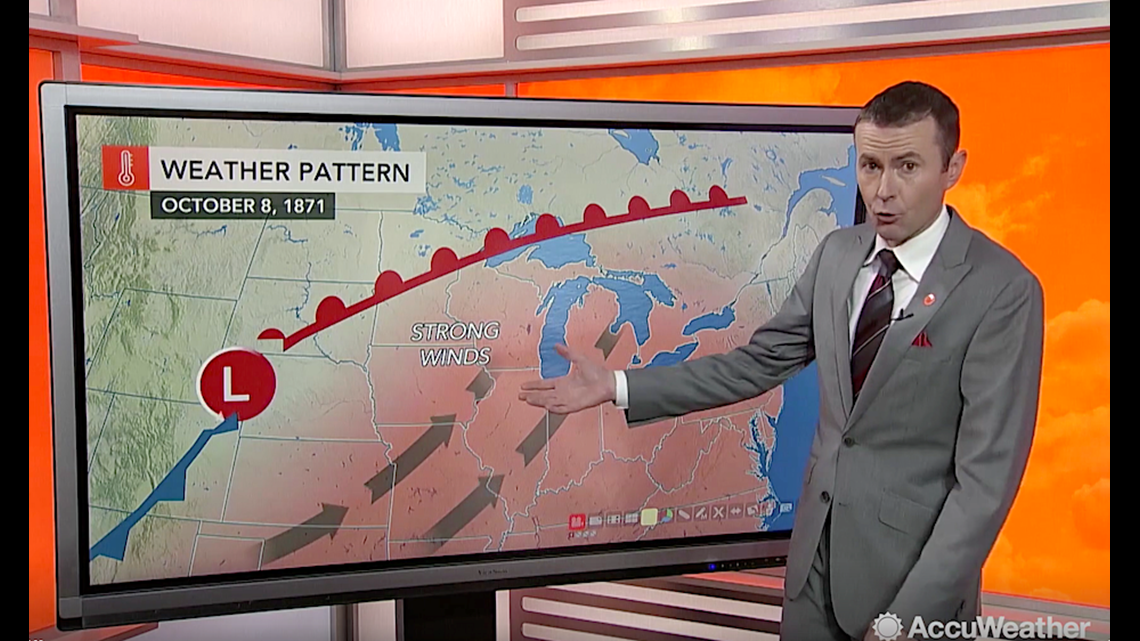

Meteorologists explain that a long period of drought, fierce winds and high temperatures all created fuel for flames -- dry trees, leaves and grass.

The fire expanded exponentially when a powerful storm over the Plains unleashed strong, warm southwesterly winds of up to 50 mph. The storm was not accompanied by much rainfall and the strong gusts fanned the flames, causing everything in its path to ignite.

"A powerful area of low pressure in the Plains ushered strong southwesterly winds and they gusted up to 50 mph in some areas, fanning the already ongoing fires and hot spots," AccuWeather Broadcast Meteorologist Geoff Cornish explained.

These winds also brought very warm and dry air across the region, providing ideal conditions for the spread of pre-existing wildfires and any new infernos that ignited.

Some may wonder how meteorologists can be certain of the weather conditions that preceded the wildfires nearly 150 years ago. Cornish explained that meteorologists' modern weather analysis is based on data gathered by NOAA, and that in the mid-19th century, the U.S. began seeing the emergence of more reliable weather record-keeping in bigger cities.

"It became common for weather observers to write down daily weather data such as high and low temps, precipitation amounts and descriptions of the sky," Cornish said, adding that the 1871 data is particularly reliable because official weather records for Chicago were kept starting that very year.

When all the fires finally stopped burning that year, 1.5 million acres of forest were left charred, and a dozen rural communities were devastated -- a catastrophe of biblical proportions that left a petrified Bible behind, showing a passage that tells of a punishing fire:

"When men in the camp were jealous of Moses and Aaron, the holy one of the Lord, the earth opened and swallowed up Dathan, and covered the company of Abiram. Fire also broke out in their company; the flame burned up the wicked," Psalm 107 reads in part, recounting a tale of a people's fading faith in God.

Whether there is meaning to those Psalms and that passage being immortalized by that terrible fire, or whether it is anything more than an interesting coincidence, is up for debate. But what's not up for debate is that what those people suffered that night still echoes to this day with those who visit the museum in Peshtigo.

"We get people from so many countries and states that can't believe that something like this has happened," Kahl said of visitors to the museum who are often aghast to learn of the Peshtigo story.

"The Chicago Fire overshadowed us," Kahl added, "but when you lose 800 people in an hour ... that's a lot of life gone."

Additional reporting by AccuWeather National Reporter Blake Naftel.