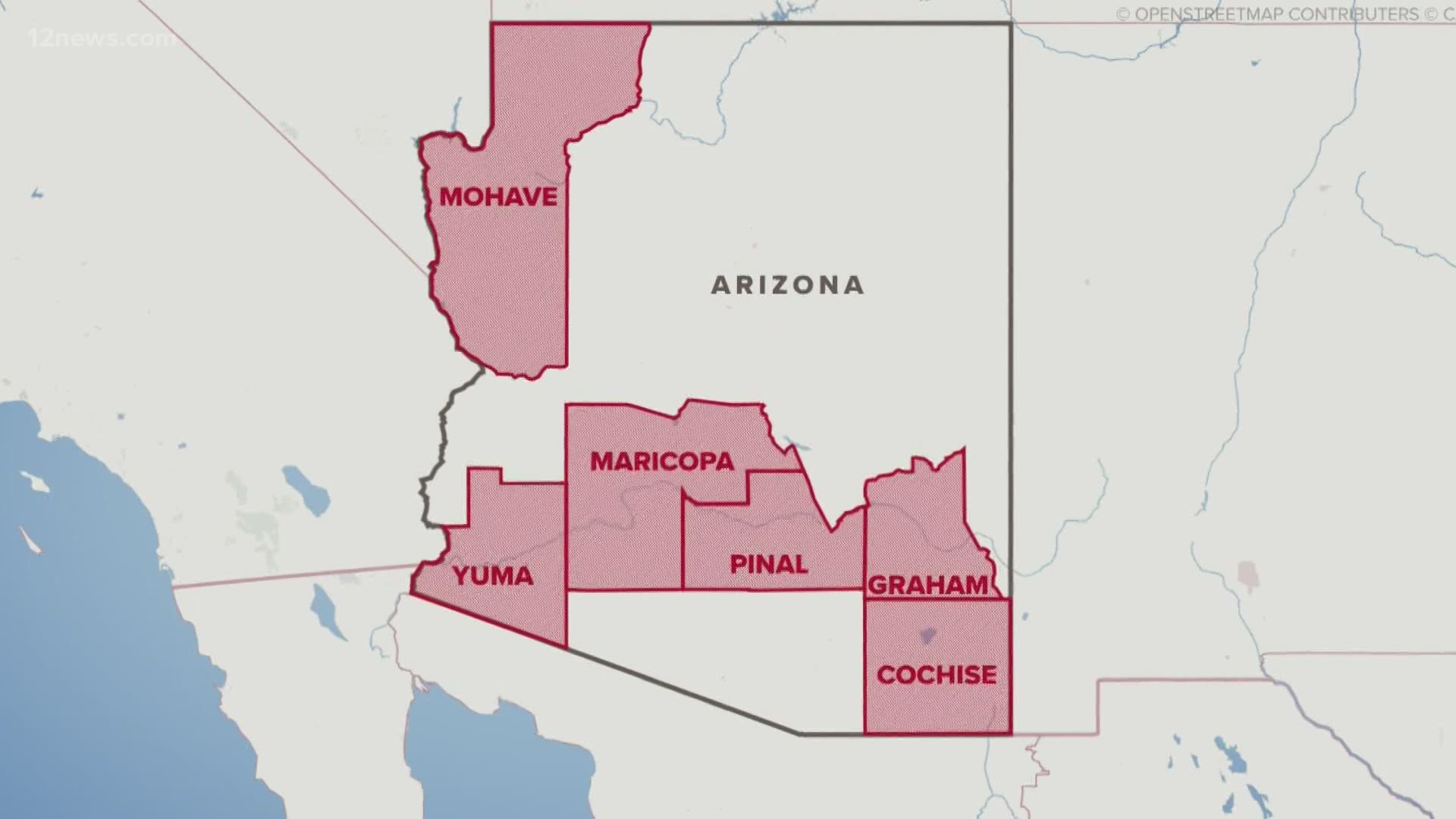

ARIZONA, USA — Six of Arizona's counties are at risk of being uninhabitable in the near future due to climate change, a ProPublica and Rhodium Group study found.

The study predicted which counties in the U.S. would face climate change issues to the point of having an uninhabitable climate for humans in the next 20 to 40 years by combining multiple metrics.

The Arizona counties listed, which included Pinal, Graham, Cochise, Mohave, Yuma and Maricopa, were among the top 100 most at-risk counties in the United States. For context, there are 3,700 counties in the nation.

The study's findings listed Pinal County in Arizona as the second most at-risk county in the United States of being uninhabitable.

Why are Arizona counties so at risk?

Arizona faces specific challenges in the near future when it comes to climate change, according to the study.

The study created multiple climate maps showing the changes in rising temperatures, rainfall, wildfire frequency, humidity, sea level rises, agriculture yields and economic damages in the United States' counties.

Pinal County faces major challenges when it comes to heat, farm crop yields, wildfires and economic damages due to climate change, which gave it a No. 2 spot on the list.

The only other county that is more at risk than Pinal County in the study is Beaufort County, South Carolina, due to rising sea levels and humidity.

The other five Arizona counties all face similar climate change problems, but in slightly lesser intensities.

They are ranked as follows:

- Graham County (No. 21 most at risk)

- Cochise County (No. 48)

- Mohave County (No. 69)

- Yuma County (No. 91)

- Maricopa County (No. 92)

"One of the things that stands out in the Southwest, which I think we already know, is the heat being the overriding risk," Dr. Michael Crimmins, a University of Arizona Applied Climatology Professor, said.

"It's getting warmer, it's largely attributable to climate change, and it's something we're going to have to deal with in the near future."

Numerous heat records were broken this past summer in Arizona, including having the hottest summer on record, the most 110-degree days and 115-degree days in a year and multiple other daily records.

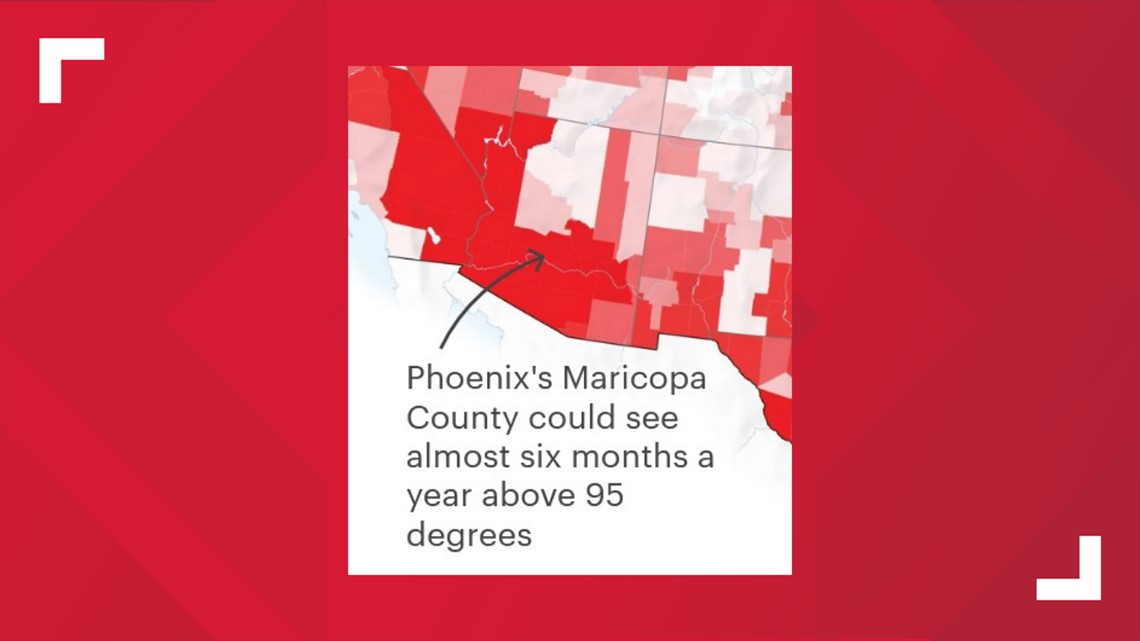

The study projects that rising temperatures will only become more commonplace in the state, threatening the state's agriculture production.

Some Arizona counties will experience temperatures above 95 degrees for more than half the year, according to the study's findings.

"The way we got to breaking those heat records this year is that the monsoon failed, and it failed in a way that we haven't seen in the last 100 years," Dr. Crimmins said.

"When it doesn't rain here and you don't have any clouds, the sun opens up on this place and it just gets really, really hot."

The lack of rainfall that Arizona saw this past summer not only attributed to the numerous heat records that were broken, but also worsened the record-breaking amount of acres destroyed by wildfires in 2020.

How accurate is the study?

Climate experts in Arizona agree with the data showing increasing heat and wildfires making the state especially at risk.

However, a national study done county-by-county has to make a lot of assumptions and the experts were skeptical regarding the study's data on "wet bulb" and farm crop yields specifically.

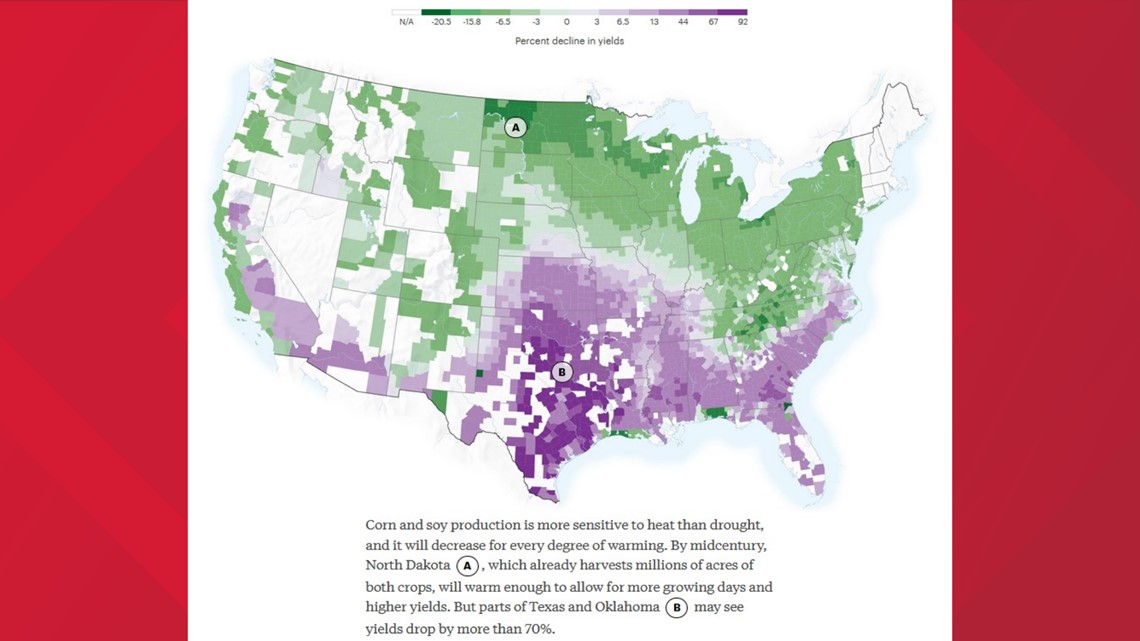

The study projected declines in farm crop yields in the state, but experts said that the uniqueness of agriculture in Arizona and the usage of water in the state may invalidate that projection.

"Some of these national-scale studies kind of make broad assumptions in how the southwest will change in a changing environment," Crimmins said.

"Arizona agriculture is really complex in the way that it adapted to this environment."

Professor Kathy Jacobs, the director of the Center for Climate Adaptation Science and Solutions at the University of Arizona, was also skeptical about the farm crop yield metric.

One of Jacobs' main areas of research is water policy, and she agreed that the innovative ways that Arizona agriculture uses water may have been overlooked in this study.

"We have seen an amazing amount of flexibility coming out of agriculture communities and we still have 70% to 80% of the water in the southwest being used by agriculture," Jacobs said.

"Also, the presumption in this study for Arizona counties is that they'll still be agriculture economies by 2050, which I'm not certain in true. There are many factors besides climate that may affect whether agriculture retains its role in the economy of these counties."

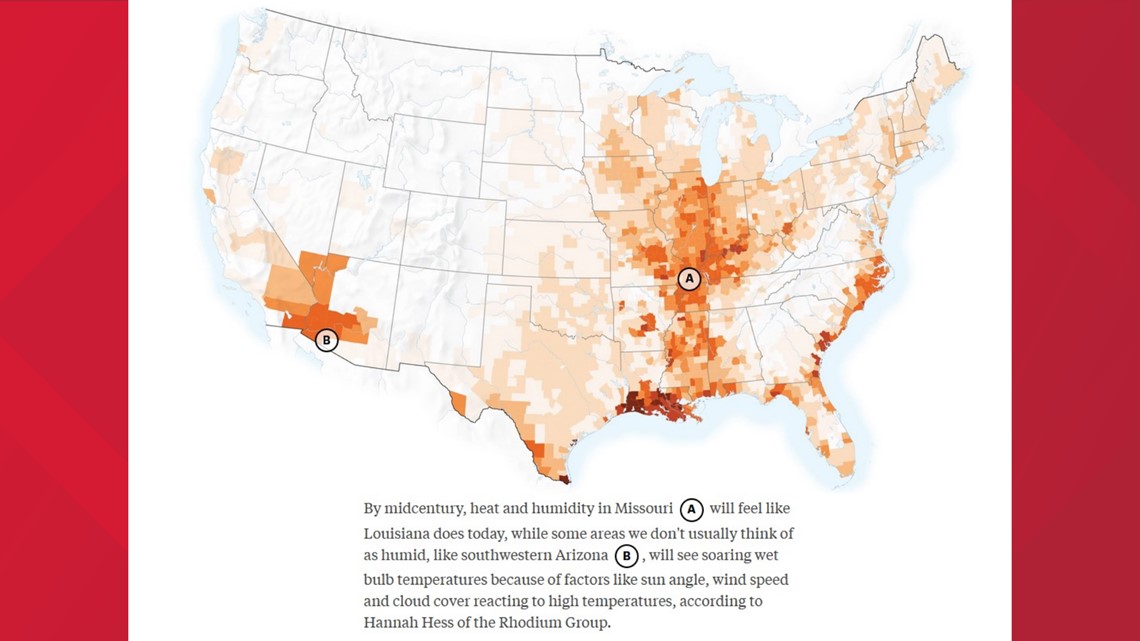

The other point of skepticism from the experts was on the study's wet bulb metric.

Wet bulb temperatures are created when the human body becomes hard to self-cool during especially high temperatures and humidity. The risk of heat stroke and deaths reportedly rises as wet bulb temperatures increase.

The study used wet bulb as one of its main factors in assessing at-risk counties in the nation. It projected that Arizona, an area not normally thought of as humid, will see soaring wet bulb temperatures in the coming years due to factors like sun angle, wind speed, and cloud cover reacting to high temperatures.

This was one of the points Crimmins was skeptical about.

Our desert state does not have that much humidity to access. Arizona may occasionally see some humidity, but the highest seen in the state does not touch the average humid points in eastern states.

"Areas like Tucson and Phoenix in the middle of summer and August will occasionally get real soupy air from the gulf of California. This takes the dew point maybe to 70 degrees," Crimmins said.

"Back east, a 75-degree dew point is the norm. That level of humidity becomes debilitating to the human body because it can't sweat and cool itself."

What can Arizonans do?

"One of the biggest problems in Arizona is that, as a state, we have not addressed the issue of climate change," Jacobs, who also has a research focus on connecting science to decision making, said.

"That's primarily because it's become political and it's unpopular of people from a particular party to have a conversation about this."

Multiple states across the country already have adaptation plans or have identified ways to work together towards some type of solution at both the state and local levels, according to Jacobs.

In Arizona, however, the vast majority of resources and the few amount of regulations the state has made are only put towards areas around Phoenix and Tucson, while the rest of the state is left to fend for itself.

"This situation between the central quarter of the state, where all the resources and regulations in the state are concentrated, and the entire rest of the state that is getting no benefit from those measures is unacceptable," Jacobs said.

"There needs to be some changes, and those have to be regulatory changes in addition to incentives and investments."

On an individual level, people in the state and across the nation have had to confront numerous problems throughout 2020: An international pandemic, civil unrest and economic downturns, just to name a few. Many may find it difficult or even impossible to add worries about climate change to their plate.

However, according to Jacobs, one of the best things Arizonans can do when confronted with all of these environmental issues is to see them as connected to, rather than separate from, the other problems we've been experiencing.

An example of this interconnection of multiple problems can be seen in a Harvard study from earlier this year.

The study found that areas which experience higher levels of air pollution and lower air quality, such as communities of color and low-income communities, were more likely to die from COVID-19 due to preexisting conditions (environment, economics, race, and disease).

"All of the problems that we're confronting today are also environmental problems," Jacobs said.

"The people of color who happen to be in disadvantaged places are all affected more than others by climate change. Labeling them as 'environmental' issues sort of implies that the environment is separate from people when, in reality, we're absolutely dependent on it, we're a part of it, and we have messed with it pretty dramatically."

You can learn more about Arizona's unique climate in our YouTube Playlist: