FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. — Snowpack provides ample gifts to the forest ecosystem and to the people who call it home.

But there are new concerns about Mother Nature’s ability to continue giving. A recently published study by NAU scientists and their partners in Minnesota suggests warming temperatures melt away snowpack levels more severely than previously understood.

Researchers monitored the duration, depth and coverage of snow for seven years in high-elevation ecosystems. They analyzed snowpack in controlled structures where they could manipulate conditions, and in open forested areas subject only to mother nature.

The findings from NAU and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory concluded that “snow presence, depth and coverage were extremely sensitive to warming.” For example, when temperatures heated up one degree Fahrenheit, the number of days with snowpack decreased by an average of one week.

Less snowpack leads to higher wildfire risks and more localized warming.

“Even slight increases in temperature led to precipitous declines in snowpack,” said NAU Forest Ecologist Andrew Richardson. He called the findings “surprising” and said they should serve as a warning to forest communities.

Springtime snow cover in long-term decline

“Flagstaff can be right at that boundary between snow and no snow. This is evidence of possible trajectory of Flagstaff itself really heading into a low snow or no snow future,” Richardson said.

That prospect may be difficult to imagine, given Flagstaff just had the first back-to-back winters of more than 100 inches of snow in at least two decades. El Nino conditions – which occur every few years – are believed to have contributed to high moisture levels this past winter.

“I do believe 2023 was an anomaly and we will be lucky to have future winters above the historic average,” Richardson said.

So, when could Flagstaff conceivably begin experiencing snowless winters - based on the study’s findings? Richardson said that would depend “on the future pace of climate change.”

“I do think we are going to see big changes in Flagstaff winters. And I think we are already seeing them,” Richardson said.

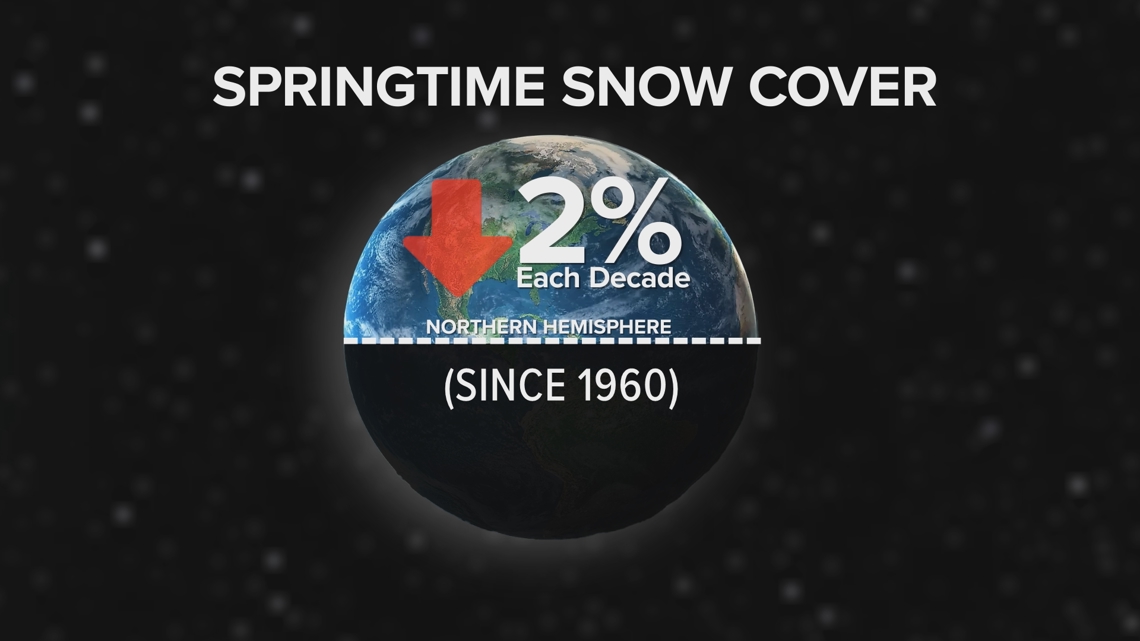

The earth has warmed about 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit since the pre-industrial age, and is projected to warm at least another 2-3 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050, according to NASA and the U.N. “Springtime snow cover” in the northern hemisphere has fallen about 2 percent each decade since the 1960s.

Flagstaff’s 30-year snow averages, tallied every ten years, have gradually declined since the 1980s, said KNAU staff meteorologist Lee Born.

“We’ve also seen extremes in the past twenty years, on both ends,” Born said.

Snow totals at Snowbowl just northwest of Flagstaff are typically at least twice as much as city totals.

Study also confirms local warming effects

It’s widely understood a strong snowpack contributes to spring runoff, plant moisture, aquifer levels and reduced fire danger. But Richardson said snow coverage plays another important role that is less often discussed: It deflects solar radiation back into space. The study confirmed how less snowpack leads to higher local temperatures near the forest floor. Meteorologists call this a positive feedback mechanism.

“As the snow starts to melt, more of that radiation is absorbed by the land surface and that has a warming effect on near-surface air temperatures,” Richardson said.

The study found the absence of snow coverage amounts to local warming of about 2 degrees Fahrenheit or 1 degree Celsius on a typical March day with strong sunlight.

“So that’s on top of already existing warming,” Richardson said.

Flagstaff declared a climate emergency in 2020

The reality of climate change is not lost on city leaders.

In 2020, council members declared an official climate emergency. City voters also approved fast-tracking thinning projects on private and federal land.

Councilmember Jim McCarthy says he believes Flagstaff’s climate may not sustain its ponderosa pine forests. In the near term, however, McCarthy says the focus is on what city leaders can control: Promoting the reduction of carbon emissions and reducing wildfire risk.

“There’s a feeling we’re susceptible to fire in a way that 20 years ago it would have been easier to control,” McCarthy said.

The city has endured severe flooding in recent years caused by scorching wildfires that wipe away vegetation in the mountains.

Richardson, a husband and father of a young girl, says he wants to balance the research with reasons to be optimistic about humanity’s future.

“We need to get the message across that changes in snowpack and water supply really threaten the sustainability of our cities in the future,” he said. “I think there’s also an encouraging emphasis on developing solar farms and wind farms and moving away from fossil fuels.”

Up to Speed

Catch up on the latest news and stories on the 12News YouTube channel. Subscribe today.