The controversy-filled history behind Arizona's Super Bowl stadium

Valley residents were treated by officials as an afterthought to the potential economic boom the stadium was touted to produce, years of previous reporting shows.

The home of Super Bowl LVII has a history full of controversy, despite it being one of the youngest NFL stadiums in operation.

The Arizona Cardinals waited nearly two decades to get a home nest to themselves. The creation of the stadium, however, ignited a long legal and economic battle that pitted Valley city officials against each other.

The cities' residents were caught in the crossfire, often treated by city officials as an afterthought to the potential economic boom the stadium was touted to produce. Local newspapers reported on the years-long mess the stadium's construction brought.

It's a long history the Valley shouldn't forget, especially as the Big Game comes to town.

Cardinals: We can't win games because we don't have seats How Arizona's long stadium battle started in St. Louis

Arizona's stadium situation began in 1987 in Missouri.

The then-St. Louis Cardinals were wrapping up a miserable decade of seasons. The team saw more losses than wins in eight of 10 seasons. In their two positive seasons, they had only achieved one more victory than defeat.

Some would blame the constant streak of losses on unfocused players, inexperienced coaches, and poor defensive schemes. The team's owner, however, saw things differently.

Fixing potential staffing and player issues wasn't the main concern of then-team owner Bill Bidwill. Instead, he believed the team's dismal record was majorly caused by their home stadium's amount of seats – or lack thereof.

The Cardinals' Missouri home, Busch Stadium, had a capacity of around 54,000 seats, which was 13,000 fewer seats than the league's seating average at that time. The potential slight increase in fans was make-or-break in Bidwill's mind, who saw attendance as a primary factor in competition, according to an interview with the Chicago Tribune.

"We`d have a competitive disadvantage and we would have to cut back on a lot of the things we do," Bidwell told the newspaper of what would happen if seating wasn't increased. "We have had the lowest NFL attendance for the last eight years, and it is time to move on."

St. Louis eventually shot down the idea of a new stadium, and even though Bidwill told the Tribune he wasn't considering moving the team, they would become the Phoenix Cardinals just a year later.

The team became tenants of Arizona State University's Sun Devil Stadium after moving to Arizona without a stadium. They would remain a tenant for 18 years and were also the only team in the NFL whose home turf was a university-owned stadium.

The Phoenix Cardinals would go on to see a decade-straight of losing seasons after the 1987 move.

Bidwill's stadium hopes refused to die, unlike fans' morale. It wasn't long before a new stadium push began.

From 'Project of the Century' to empty lot The first push for a Cardinals stadium ends after massive Mesa opposition

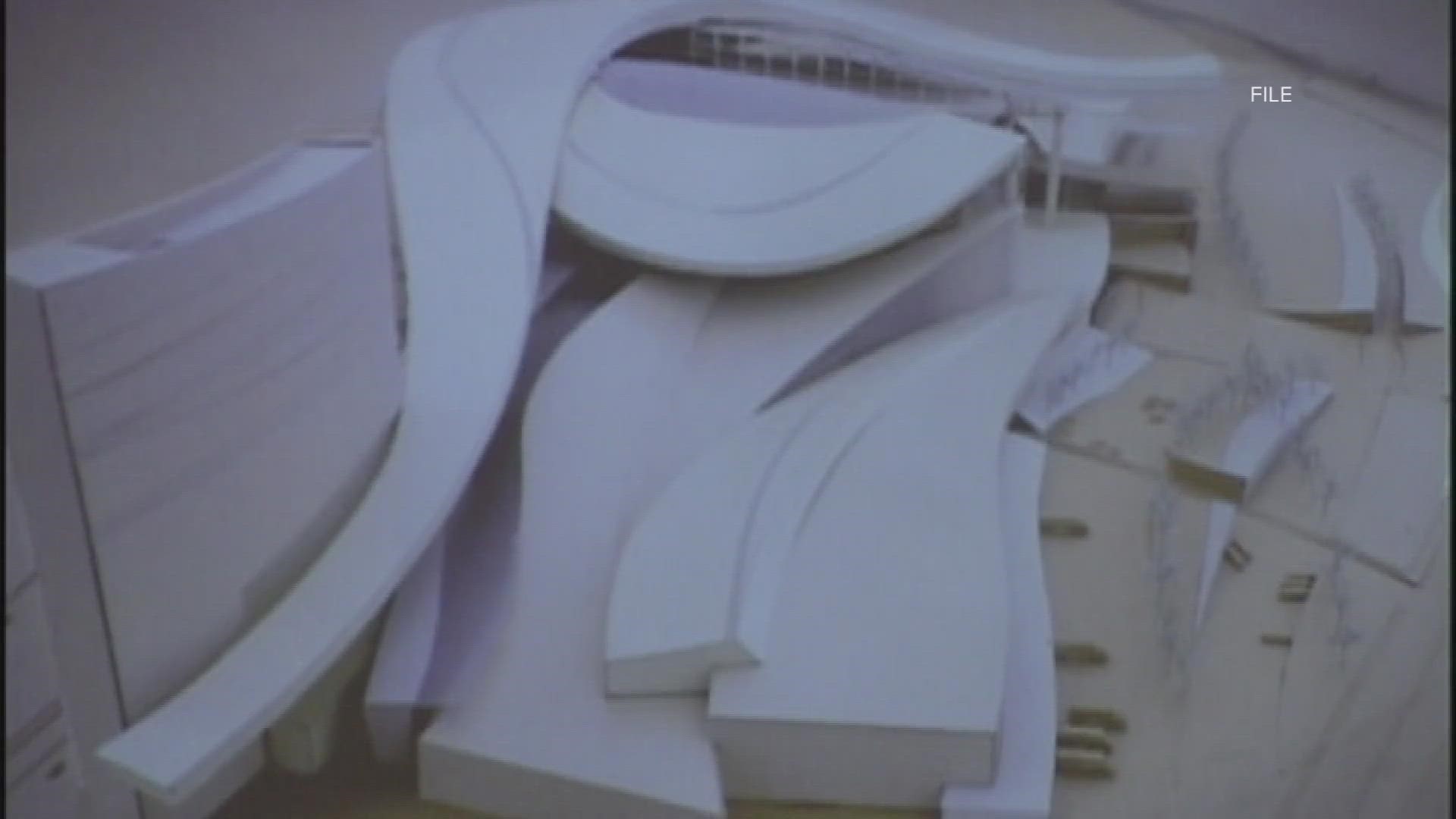

Mesa city officials were the first to offer a stadium site in 1999, spurred in part by an NFL commitment to hosting a Super Bowl in Arizona once the stadium was built.

The city's Rio Salado Crossing, dubbed the "Project of the Century," was planned to be a $1.8 billion shopping and convention district that would also house the stadium.

Discussions between Mesa City Council and the Cardinals ended with a large chunk of the district's gains going toward the team rather than the city, including the vast majority of parking revenue and much of the sales tax revenue.

The project had to get voters' say before it could break ground. Residents in Mesa, Queen Creek and Gilbert had to approve a sales tax increase to pay for $385 million of the district's construction.

Residents' opposition to the project started immediately after the news was released.

The stadium was the top topic of conversation for people across the Valley, with archived Arizona Republic newspapers reporting it being the biggest talking point in letters to the editor for weeks on end.

"Missives in support of the stadium are as rare as Cardinals' victories," the newspaper said.

Opposition to the stadium was by far the most-shared opinion among mailers, including scathing quotes like:

- "[The Cardinals] think since they got into the playoffs that we dumb Mesa voters are going to vote them a new stadium, they are out of their minds," said Charles Burrier of Mesa.

- "The National Football League is ... attempting to hold the citizens of Arizona captive to their desires ... the average citizen being asked to fund this project cannot even get a ticket to the Super Bowl," said Doug McClymont of Cave Creek.

- "This is a childish, macho game the taxpayers are all being forced to play at the taxpayers' expense," said Robert Wolfe of Scottsdale.

Opposition intensified when the deals' details were released. Mesa's residents would be stuck with the sales tax for 20 years while the Cardinals would recoup their portion of the investment in the first few years, according to a Phoenix New Times report.

The resident's resistance would prove resilient.

Mesa voters defeated Rio Salado Crossing by a 3-2 ratio, even though the opposition was reportedly outspent "50-to-1."

"It failed, very simply, because people saw this Rio Salado Crossing for what it was: a cash cow strictly for the Cardinals," David Molina, a member of the Tri-City Partnership for Tax Relief, told the Arizona Republic after the vote.

"It was basically a zero-sum benefit for the average citizen here in Mesa."

Mesa residents' voices were heard: they didn't want the stadium. State government officials, however, were about to show how scared they were to lose the Cardinals.

When the Cardinals almost flocked to Texas Governor searches for stadium solution to keep the 'Arizona' in Arizona Cardinals

Rumors immediately began to spread speculating the Cardinals were going to pull another St. Louis-like stunt and leave Arizona after stadium plans failed.

A Houston businessman named Bob McNair, who had an agreement with Texas' Harris County Sports Authority to build a $310 million stadium, offered to relocate the Cardinals to southeast Texas, according to The Associated Press.

Rumors of other cities hungry for the Cardinals slithered all the way to the top of Arizona's state government.

Then-Governor, and apparent huge Cardinals fan, Jane Hull announced the formation of a task force focused on securing a site for the stadium just months after Mesa voters refused it.

"It is in our state's best interest for leaders in both the public and private sectors to give [the stadium] serious thought," Hull wrote in a letter obtained by the Arizona Republic.

The task force immediately telegraphed it was working for state interests rather than the public good with its first major action as a state-run body excluding the public from its meetings.

Before the task force could start hearing pitches from cities, another initiative had to get voter approval. Proposition 302 needed to convince voters to raise hotel and car rental taxes in Maricopa County, partially for stadium funds.

The debate over "if" officially ended when 54% of voters approved Prop 302.

The debate over "where" began right after.

Residents want West Valley, officials chose Tempe The first of many inter-Valley stadium conflicts kicks off

Tempe was one of the first to enter the stadium fray.

The city made sure to catch the state's eye early, spurred by worry they would lose the now-Arizona Cardinals, along with the thousands of dollars and national exposure the team brought it. Tempe proposed six sites along Route 202 near the newly filled Tempe Town Lake.

"We don't want to be left out," then-Mayor Neil Giuliano told the Arizona Republic. "It's very important for Tempe to show we have some viable sites."

The West Valley emerged as a strong contender not long after Tempe submitted its bid.

The West Valley's presentation to the Arizona Sports and Tourism Authority (AZSTA), a board created by Prop. 302 to handle stadium talks, was fueled by the most in-person supporters of any of the sites, according to the Arizona Republic. Representatives included mayors from seven West Valley cities, including Glendale and Peoria.

The area's proposal already had a leg up on Tempe's with fewer unchecked requirements. While the West Valley's only issue was finding a developer to turn a cotton field into a stadium, Tempe faced numerous other problems, including:

- More expensive foundation work

- A $1.8 million lease of SRP land

- A $37,000 monthly water bill not originally included in the proposal

- Developing an adjacent exhibit hall

- Getting communities to guarantee they'll hold events there

Another win for the West Valley: How its residents voted on Prop. 302.

Voting maps showed the majority of the West Valley approved the proposition that paved the way for the stadium, while much of Phoenix and the East Valley disapproved of it.

Residents' approval of the site was solidified by an Arizona PBS poll that found 51% of Maricopa County wanted the stadium to be built in the West Valley, compared to just 15% approval for a Phoenix site, 6% for Tempe and 4% for Fort McDowell.

Despite all signs pointing towards the West Valley, the Arizona Cardinals endorsed the Tempe stadium site on Feb. 14, 2001. The move left the West Valley feeling betrayed.

"This alienates half of your fan base," Cardinals fan Dave Iwanski from Glendale told the Arizona Republic. "I'm not a lukewarm fan, but I am certainly disappointed. Aren't we the Arizona Cardinals?"

AZSTA would crown Tempe as the stadium's home soon after, helped by the Cardinals' additional offer of $18.5 million.

The East Valley city celebrated the win, but the celebration wouldn't last for long.

Stadium's second push labeled 'air-traffic hazard' The Cardinals' stadium in Tempe that never was

Tempe won the stadium battle, but it would very publicly lose the war.

A new issue emerged before the city could even break ground on the stadium site: the structure would potentially cause dangers for airplanes.

Phoenix's Sky Harbor International Airport expressed its concern two days after the site was awarded to Tempe, saying the stadium's location and height would "severely impact" arriving planes. At the stadium's highest point, planes would only be flying 170 feet overhead.

"One hundred seventy feet is not enough clearance at a critical time of flight, such as arrival," Suzanne Luber, a spokeswoman with Sky Harbor, told the East Valley Tribune on Feb. 16, 2001.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) would later confirm AZSTA never asked whether the stadium would impact flight travel, even though the site lay directly east of Sky Harbor's longest runway.

Opponents of the stadium demanded an investigation into the site selection process and why the authority didn't address air safety issues sooner.

In an attempt to appease aviation officials, the authority announced it would lower the stadium into the ground, with the field sitting 36 feet underground.

The FAA wasn't appeased.

Five months after Tempe won the site, the city lost it when the site was officially labeled a "hazard."

The FAA couldn't force the stadium's construction to stop, but the designation would open Tempe and the state up to lawsuits if any issues arose after the stadium was built.

Officials didn't want to take that risk and the stadium's construction was halted.

The authority, however, remained firm that Tempe would be the home of the Cardinals.

"I haven't heard anything to date to give me any doubt that the stadium will be built on [the Tempe] site," Jim Grogan, AZSTA's chairman, told the Arizona Republic.

Tempe disagreed with Grogan, expressing its lack of hope by exiting financial talks on the stadium in August. The Cardinals, still holding on to hope, paid the entire $18 million tab for the land lease.

That land seemed destined to stay undeveloped. Nearly eight out of 10 Maricopa County residents wanted a new site chosen for the stadium, one that wouldn't threaten the safety of airplanes, according to an Arizona Republic poll on Aug. 30.

The FAA was set to release a full report on its Tempe stadium site findings on October 8, 2001. Those plans were indefinitely put on hold after 9/11.

In light of the Tempe issues never being resolved, AZSTA announced it would reopen site applications in December, officially ending the stadium's second push.

The stadium's third and final push would be even rockier than the second.

Stadium almost 'destroyed' historic Phoenix neighborhood Garfield residents' fight to reclaim streets from drugs and crime nearly undermined

Phoenix would deliver a series of site pitches at the start of the stadium's third push in January 2002. The sites had "a lot of potential," the president of the Downtown Phoenix Partnership, Brian Kearney, told the Arizona Republic.

Residents could only see potential destruction while businesses focused on potential money flow.

At-risk Phoenix residents were put in harm's way in both of the proposals, according to the Arizona Republic:

- A 35-acre site near Jefferson Street and Eighth Avenue would raze a homeless shelter

- A 42-acre site near Fillmore and Seventh streets would bulldoze some of a historic neighborhood's homes, displacing around 180 residents

The area that the 42-acre site threatened is called Garfield Neighborhood. It was developed in 1883 as one of the first expansions to the original Phoenix townsite.

The neighborhood had become known for drugs, prostitution, and crime in the late 1990s, according to Arizona Republic reports. A group of the neighborhood's residents had started fighting back to reclaim their streets by encouraging homeownership in the area. The group argued the stadium would undercut their efforts after years of making progress and improvements.

"In your right mind, who would want to live next to a stadium?" President of the Garfield Organization Helen Trujillo told the Arizona Republic. "Do you think that's going to encourage homeownership? I don't think so."

The Garfield Neighborhood site was the only one of the 18 proposals offered to AZSTA that would require the destruction of homes and the moving of families for the stadium. In spite of this, the downtown site ended up in the authority's top five picks.

A glimmer of hope appeared for the neighborhood when a Phoenix City Council advisory committee acknowledged the stadium would be detrimental to the community. The committee recommended a stadium site near 40th Street and Loop 202 instead.

"That neighborhood would basically be gone," panel member Jenine Doran told the Arizona Republic.

The residents' relief was short-lived.

Just weeks after the advisory panel's decision, Phoenix City Council members did a 180 and endorsed the Filmore and Seventh streets' site. The backtrack was because the location near Garfield Neighborhood would capitalize on parking and entertainment venues already near the area, city council officials told the Arizona Republic.

"We're willing to chain ourselves to the bulldozers to stop the stadium," Beatrice Moore said during a protest outside Phoenix City Hall.

The Phoenix stadium would never break ground despite the council's endorsement. The failure wasn't due to the concerns of the neighborhood's residents, but rather the city's refusal to include a rollout natural turf field and a 2,000-space parking facility in its plans. AZSTA saw those lacking requirements as the final nail in the coffin.

Garfield Neighborhood was safe, but there were still four other sites vying for the home of the Cardinals.

Stadium finally finds a home in Glendale After being cut from the competition twice before, the West Valley was begged by the state to take the stadium.

The stadium's eventual winner was a city that lost the bid twice before.

Glendale was the first to pitch its site during the stadium's final push. Fresh off its 2001 battle with Tempe, the West Valley city offered a sizable 240 acres of farmland.

The proposal had other incentives for the stadium, including:

- A site just south of the already-approved Coyotes hockey arena

- A commitment of $10 million in construction costs from Glendale

- The support of seven West Valley mayors

The incentives weren't enough. Two months later, Glendale was also the first to drop out of the race, folding before Phoenix's stadium plans fell through.

Glendale representatives believed AZSTA had a bias against any stadium sites in the West Valley.

"There have been accommodations made that just don't seem to be fair," then-Glendale Councilman Manny Martinez told the Arizona Republic. "These changes have been made, and it's really to accommodate Phoenix."

Only the Mesa, Tempe and the Gila River Indian Community site proposals remained.

Tempe was the first of the three to drop out after a land-swap deal with Mesa fell through.

"Our understanding is Mesa desires to go this alone, and we wish them well," Tempe Mayor Neil Giuliano told the Republic on March 5, 2002.

Gila River was next on the chopping block, forced out of the race due to a Maricopa County legal analysis that found tribal lands could not host the stadium.

Mesa was now the only site in the running, but the city wasn't any closer to becoming the Cardinals' home nest. Mesa was short around $8.6 million in funding for its site near the southeast Loop 101 and Loop 202 junction.

The plan to generate the money? Hold another election asking the city's voters to support the stadium.

Not even Mesa officials seemed confident the vote would pass.

"It's possible Mesa will end negotiations," Mesa Councilman Mike Whalen told the Arizona Republic. "I'd rather have a good relationship with my neighbor than a football stadium."

With nowhere else to turn, AZSTA asked one city to reenter negotiations: Glendale. The West Valley city renewed talks with the authority on two conditions:

- City costs to build the stadium had to be kept low

- Glendale had to be the exclusive stadium site under the authority's consideration

The authority agreed. Soon after, Glendale was awarded the stadium with a 7-1 vote. The only board member who voted against the city was Roc Arnett of Mesa.

"At the end of the day, I think we will all be proud of this facility," board member C.A. Howlett told the Arizona Republic.

Where the stadium stands today What's left after a multi-year battle between the Valley's cities?

Whether all Arizonans are "proud" of the Cardinals' home is still up for question.

For starters, former owner Bill Bidwell's philosophy that more seating equals more wins hasn't held up. The team has had only six winning seasons in the 16 years since the stadium's construction. The team's 2022 season ended with only four wins.

Another thorn stuck in Arizonans' side is the stadium's price tag.

The Cardinals' home would go on to incur around $351 million in construction costs. AZSTA was on the hook for $221 million of the final costs after the Cardinals paid around $130 million. The state is still working to pay that price.

The authority has only paid back around 20% of those costs in the stadium's nearly two decades of operation. The majority of those costs have reportedly been paid through bond offerings.

"The current balance of the outstanding bonds is $178,970,000," an authority representative told 12News. "Some of these bonds have been refunded over time with new bonds, and we still have bonds outstanding."

It's unclear how much, if any, of the 2023 Super Bowl's revenue will go toward paying off the remaining construction debt, especially since this is the third Big Game the stadium has hosted since being built.

The stadium has also recently come under fire for failing over 75 fire inspections since 2017.

Blocked exits, unsecured hazardous materials and defunct fire extinguishers are just a few of the repeat fire safety violations found at State Farm Stadium by the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management Office of the State Fire Marshal in more than 100 inspection reports from August 2017 to February 2022.

Super Bowl LVII

Get the latest information on Super Bowl LVII on the 12News YouTube channel. Don’t forget to subscribe!