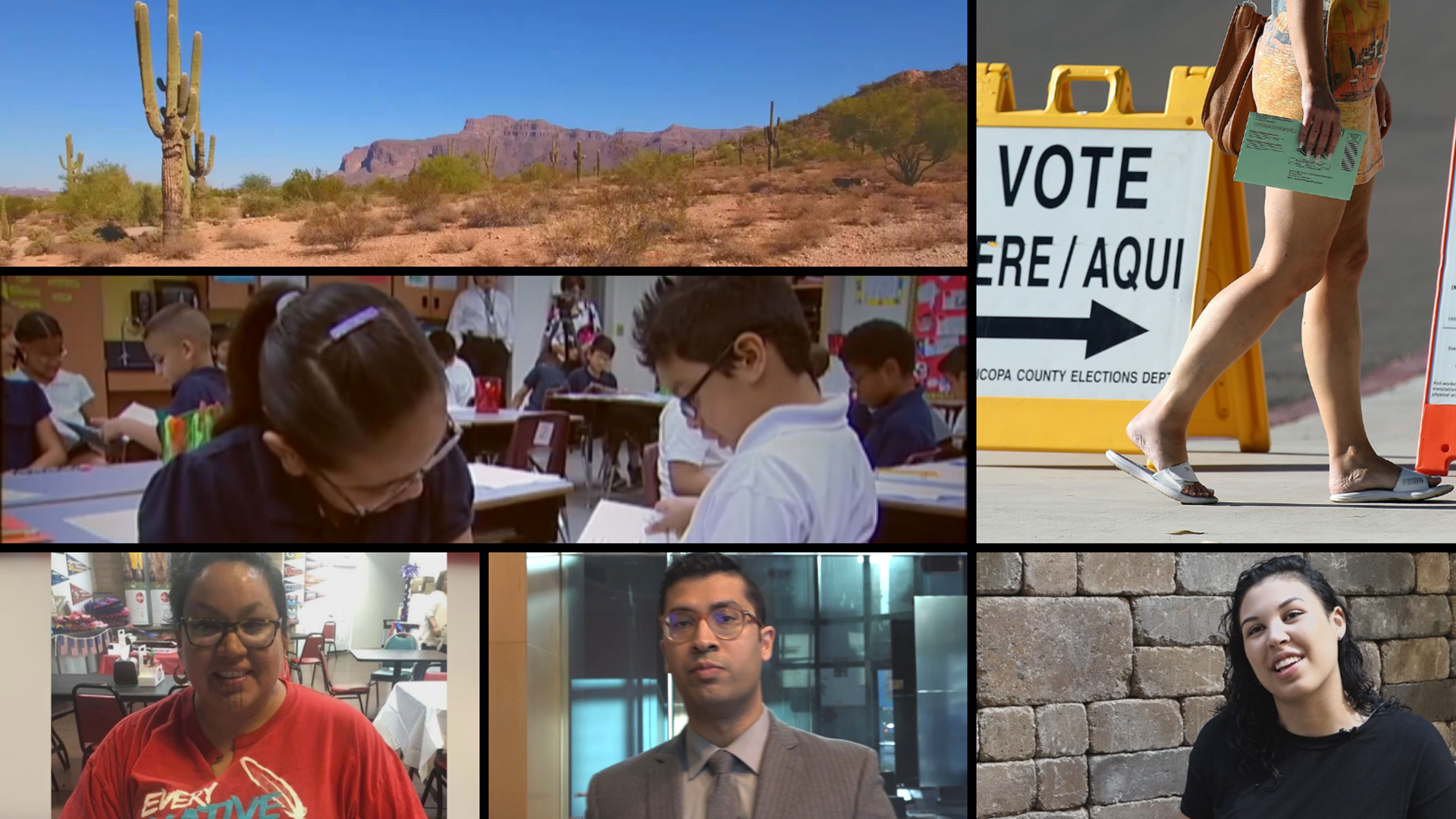

The Changing Face of Arizona

Arizona is a little more than a decade away from becoming a majority-minority state.

The shift will happen 15 years before the country’s demographics are expected to shift, according to U.S. Census Bureau numbers. Arizona could be the model for how the United States responds to the changing demographics of Americans.

Arizona will need to evolve in legislation, voting, education, economics and immigration to support its changing demographics.

Census data shows 30 percent of Arizona’s population is Latino, about four percent is black or African-American and three percent is Asian and another three percent is two or more races.

Marshall Trimble, the state's official historian, calls Arizona an amalgamation. "You melt something together and it’s stronger," he said.

To understand how Arizona interacts with race, we must first define it. Race is often conflated with ethnicity or ancestry, but in fact, there is no real biological component to race; 99.9 percent of the human genome is identical across all people.

Despite that, race has been used to shape Arizona’s history for better and for worse.

Arizona's sordid history with race can be seen in snapshots of legislation. Its legislature passed the infamous racist law Senate Bill 1070, which was shut down by the Supreme Court. The state has a record with voter suppression by requiring a Voter ID and making ballot collection — a method used mostly by voters of color — a felony. Arizona, being a border state, is also part of the national conversation of immigration.

Trimble says without its Native American and Mexican roots, Arizona wouldn't be what it is today.

While Arizona has a sense of pride in those roots, it hasn't been without issue, especially when it comes to immigration and representation.

The majority of Arizona's immigrant population are from Mexico. Immigration will continue to contribute to Arizona’s and the nation’s population growth. According to Census data, immigration will overtake natural increase (excess of births over deaths) as the primary reason for population growth in the U.S. by 2030. Yet immigration legislation is far from being reformed.

"Arizona was kind of the testing ground for the far-right, hate-based legislation against immigrants. And now we’re seeing the Trump administration and (former attorney general) Sessions taking that to a much bigger scale," immigration attorney Ybarra Maldonado said.

Even more so, a group on the Tohono O'odham Reservation is fighting for representation in Arizona's electorate. Today, 22 tribal nations make up more than a quarter of state land. Native American representation in government positions, however, is still being measured in firsts.

Much like Tohono O'odham members are fighting for a seat at the table, Latinos are fighting for better seats in the classroom. More than half of the students in Arizona's public schools are Latino, yet a sizeable educational achievement gap remains.

The state is responsible for closing that gap, but one school district could be the model of success. Nearly all of the district’s students are non-white and come from low-income homes, but they are graduating at a higher percentage than Arizona's statewide graduation rate.

The educational achievement gap matters beyond just school as today's students will be tomorrow's workforce.

A 2012 study by the Morrison Institute of Public Policy at Arizona State University found that if nothing is done to close the gap, the number of Arizona adults with less than a high school education could rise over 60 percent, from around 524,000 in 2010 to 858,000 in 2030.

That would affect the state's economy as more qualified workers are needed as Arizona's knowledge-based industries, such as technology, continue to grow.

Today in Arizona, Latino-owned businesses are growing faster than other ones. But they could be growing even faster and adding more to Arizona’s economy if it weren't for hurdles Latino business owners face that are less common for white business owners.

To support the economic impact that Latinos have on the state, it's important that the Latino voice is heard.

Yet, much like Latino business owners, Latino voters are also disproportionately met with obstacles when casting ballots compared to white voters. If those obstacles are dismantled, the state's vote could change from red to blue — something Arizona had a taste of in the 2018 midterm elections.

Being a minority in a state that has a complicated relationship with race comes with certain complexities. In Arizona, the main storylines often focus on Latinos and Native Americans. In reality, while those groups make up a larger percentage of the state's population, the issue of race can be much more nuanced.

The Census Bureau says the population of people who are bi or multiracial is projected to be the fastest growing racial or ethnic group over the next several decades.

Aliya Mateen, a 22-year-old woman living in Phoenix, speaks to issues bi or multiracial people experience that may vary from other minorities.

"The whole entire life that I’ve lived has been a gray area in societal standards because I don’t mesh into one of those boxes. I’m the ‘Other’ box," said Mateen, whose father is black and mother is white. "I don’t want to be in that box but I don’t want to be forced to pick another one either. There should be a box for me.”

The face of Arizona is changing. The imminent majority-majority shift will impact statewide social sectors and those changes are unfolding right now.

"When change is inevitable, you can either embrace it, work with it, guide it and try to be successful and benefit for all; or you can resist it, which is futile—which I think we’re seeing somewhat— but the change is going to happen anyway," the Morrison Institute's Director of Latino Policy Joseph Garcia said. "The data don’t lie. We know what the future’s going to look like."

So, Arizona, it's your move.

The Changing Face of Arizona is a special project by 12News.com staff.

Project staff:

Alejandra Armstrong, editor and reporter

Anne Stegen, editor and reporter

Elizabeth Wiley, digital director

Mackenzie Concepcion, reporter

Yolanda Garcia-Espinoza, reporter

Takira Jackson, reporter

Michael Nowels, reporter

Hayden Packwood, reporter

Caylee Scott, reporter

Gabe Trujillo, reporter