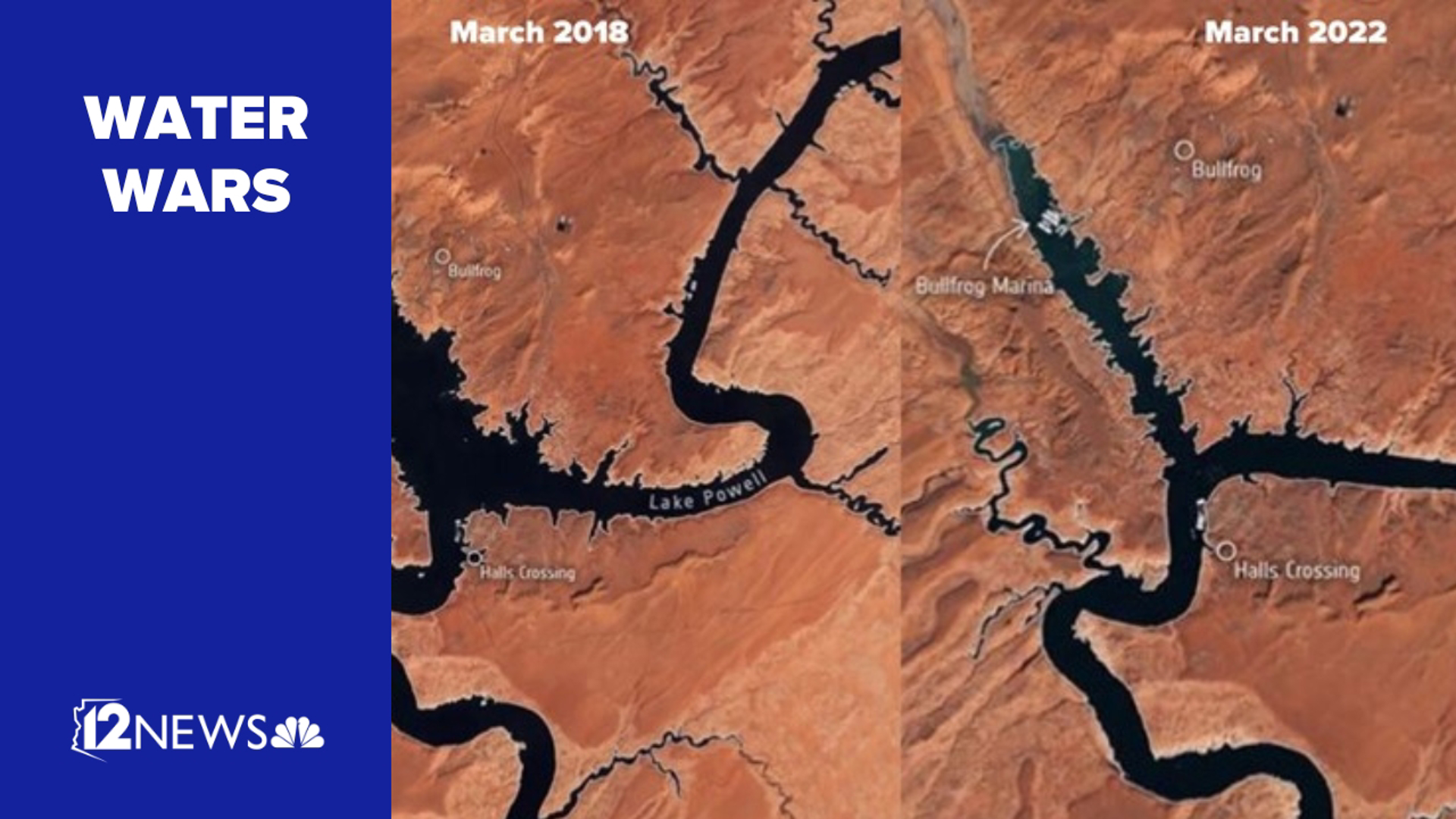

PAGE, Ariz. — The drying up of Lake Powell is much more apparent for someone who's at Glen Canyon Dam every day.

“It's tough to see," Gus Levy with the Bureau of Reclamation said, standing in the visitor's center. "I've been here since 2007 and obviously this is way lower than I've ever seen it.”

Levy is the acting manager of Glen Canyon Dam and the power plant housed within it. He's watched the water on the other side drop to levels no one's ever seen before.

The lake's water is measured in terms of its elevation above sea level. Water levels fluctuate constantly, but in 2022, the water dropped below 3,525 feet above sea level.

That was a critical point for the Bureau of Reclamation. It's a warning that the water could continue to drop and if it does, the dam could shut down.

See a nearly 40-year timelapse of Lake Powell's dry-up from Google Earth here:

Hydroelectric power plants work by using the weight of the water in a lake to push it down pipes and into a generator. The water spins the turbine, generating power.

The dam's minimum power pool is 3,490 feet. It's the level Levy hopes he will never see.

"Then you would start to uncover the intakes," Levy said. "The pipes that actually convey the water down to the generator."

If those pipes are uncovered, there's no way for water to be fed into the power plant. Any air that made its way into the system would damage the generators.

The power plant is already producing less power than it could because the water weighs less than it used to. And if it shuts down completely, Levy said it would put a strain on the Southwest's power grid because the dam acts as a stopgap that takes stress off the power grid in times of high use.

“I would say the real value of this place is our ability to ramp up and come back down," Levy said. "Provide stability to the grid."

RELATED: Arizona's cities may see 'huge' water cutbacks soon. Here's what that means for Valley residents

What about 'Dead Pool'?

The minimum power pool isn't even the worst-case scenario. The worst part is 130 feet below that at what's called Dead Pool.

Dead Pool is the lowest the lake can go and still let water through the dam, if not the power plant.

The power plant would be long dormant if water reaches this level, but there are bypasses at a lower level than the power plant that releases water around the side of the dam and down the Colorado River.

Because Glen Canyon Dam sits on the Colorado River, the Grand Canyon would theoretically run dry at Dead Pool unless additional measures were somehow taken.

“I would say that right now Lake Powell is the most immediate concern," said Sarah Porter with ASU's Morrison Institute for Water Policy.

“The system isn't behaving the way it was built to behave. More snow may be evaporating into the atmosphere, the ground is hotter and drier and so it's retaining more of the water."

Experts now believe the 22-year drought that the West has been facing may not only be the new normal, but it may always have been normal.

Over-allocation: a long-time problem

“They over-allocated the river from the beginning," Levy said. "Based on hydrology from the previous 30 or 40 years. When they did that, that was an extremely wet period."

Those decades of hydrology research were considered normal when the first water agreements for the Colorado River were taken.

But researchers know now that they weren't normal...they were the outliers.

“The water use that we're using now, nature can't keep up," Levy said.

There's nothing that policymakers and researchers can do about the weather or the amount of snow and rain that falls in the West and makes its way downriver. The only thing they can do is reduce the amount of water we use for everything from daily use to agricultural use.

The Bureau of Reclamation has reduced the amount of water being released from Glen Canyon Dam this year. It has also sent water downstream from other reservoirs to help stabilize Lake Powell.

But all of those measures are all temporary fixes for a long-term problem.

Water Wars

Water levels are dwindling across the Southwest as the megadrought continues. Here's how Arizona and local communities are being affected.