SACATON, Ariz. — Joe Rosenthal's Raising of the Flag on Iwo Jima is one of, if not the single most, iconic images of the 20th century.

But did you know that one of the Marines in the photo was a man from Arizona? Today is the 79th anniversary of that accomplishment.

Ira Hayes, born Jan. 12, 1923, near Sacaton at the Gila River Indian Community lived a short but incredible life — a life marked by triumph and tragedy in equal measure.

Hayes was the oldest of six children and his father was a World War I veteran who farmed cotton at the Gila River Indian Community. Hayes enlisted in the Marine Corps, the same branch as his dad, in August 1942 when he was just 19 years old.

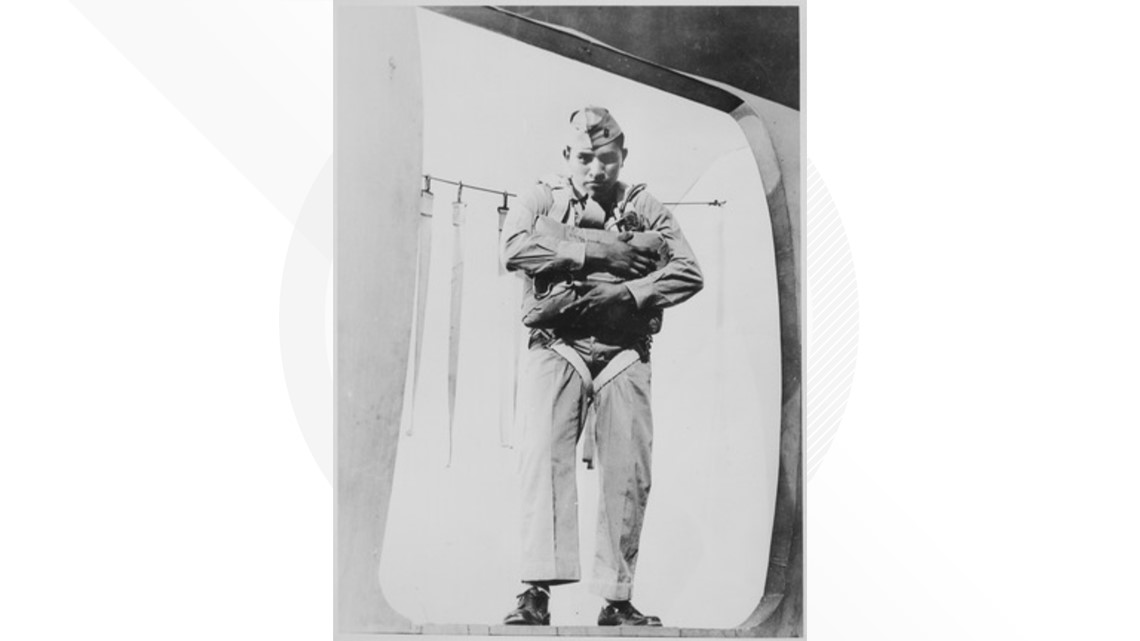

When he was finished with recruit training in San Diego, Hayes was assigned to Marine paratrooper training at Camp Gillespie. Accounts differ between Arlington Cemetary and the United States Department of Veterans Affairs on whether or not he volunteered. Regardless, it was there that he got his silver wings and the nickname Chief Falling Cloud.

In March of 1943, Hayes shipped out to New Caledonia and spent the next 11 months in the Pacific theater. He served in battles at Vella Lavella Island and Bougainville Island before returning to San Diego in 1944, according to the VA. The Marine Corps parachute units disbanded around that time, and Hayes transferred to the 5th Marine Division — the same one that would be deployed at Iwo Jima.

Then, 70,000 men set out to take the rocky Pacific island. Nearly 7,000 of them died trying. Of the 20,000 Japanese defenders, only 216 survived.

Hayes sailed to Iwo Jima from Hawaii, landing on Feb. 19, 1945: D-day. Hayes would spend the next month fighting on the island, and it was there he made his mark on history.

On Feb. 23, four days after he landed on the island, Hayes and five other Marines raised the U.S. flag atop Mount Suribuchi to signal to the other soldiers that they had taken the mountain.

That's Hayes on the far left, with his arms outstretched towards the flagpole. Of the 45 men in his platoon, he was one of five survivors by the end of the prolonged battle. Three of the other flag-raisers, Michael Strank, Franklin Sousley and Harlon Block, were killed before the battle for Iwo Jima was over.

Hayes remained on the island during the fighting until March 26 when he returned to the United States. He would be promoted to corporal later that summer. By the end of the war, Hayes and Company E of the 29th Division traveled to Japan to help with the occupation and reconstruction efforts. He stayed there for a few months until returning to San Francisco.

On Dec. 1, 1945, Hayes was honorably discharged with several decorations and accolades.

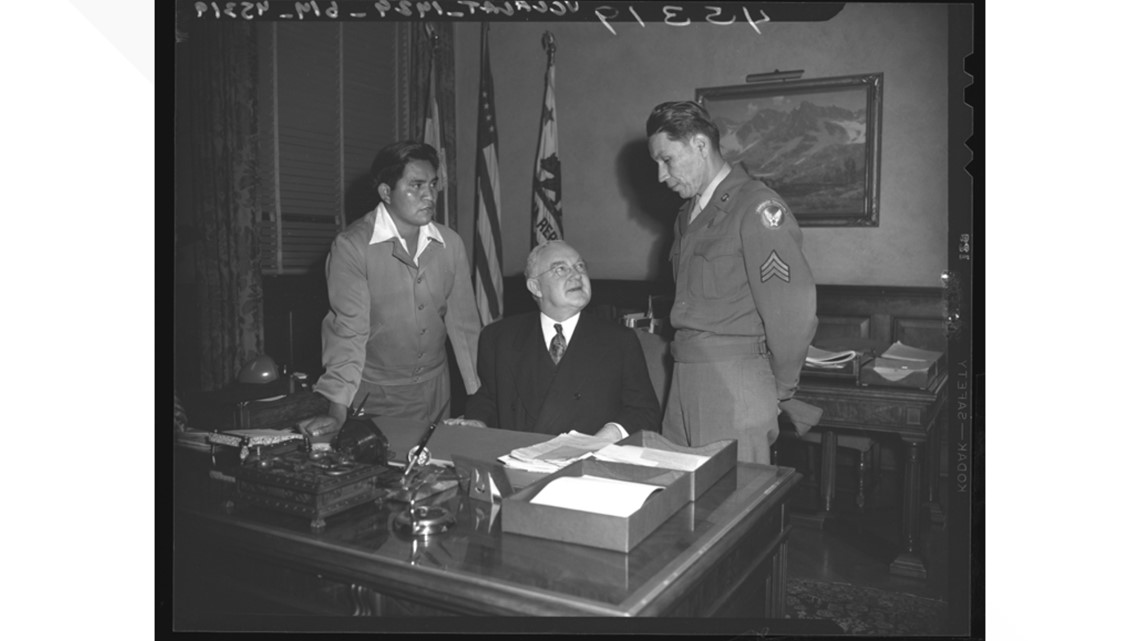

Following the war, Hayes was in and out of the public eye. He made a brief appearance as himself in the John Wayne film, "Sands of Iwo Jima," and frequently met with politicians to protest discrimination against Indigenous peoples in America.

But Hayes was suffering. As Michael Robert Patterson with Arlington National Cemetery put it, Hayes "[left] behind in a mass graveyard on the island the best friends he ever had."

Neither Hayes's profile with the VA or the Department of Defense note the severe struggles with PTSD and alcoholism that Hayes faced after his return to civilian life. Even once he moved back to the Gila River Reservation, Hayes was still getting hundreds of letters and more recognition than he felt he deserved.

"I was sick. I guess I was about to crack up thinking about all my good buddies. They were better men than me and they're not coming back. Much less back to the White House, like me," he was quoted as saying in Herman J. Viola's Warriors in Uniform: The Legacy of American Indian Heroism.

In November 1954, the U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial was unveiled in Washington D.C. President Eisenhower praised Hayes as a national war hero. Just a few weeks later, Hayes died.

He was found dead near an adobe hut in Sacaton early in the morning on Jan. 24, 1955. Hayes had been playing cards with two of his brothers and some friends the night before. While accusations of a fight were thrown around, the Pinal County coroner ruled that Hayes' death was caused by exposure and alcohol poisoning. Hayes was not given an autopsy.

At only 32 years old, Hayes was given "the biggest funeral in the history of Arizona," according to Arlington National Cemetery. On Feb. 2, 1955, Hayes was laid to rest in Section 34 of Arlington National Cemetery where his grave still stands.

THOSE WHO SERVE

12News is honoring the brave people who are currently serving and have served in the United States' armed forces.