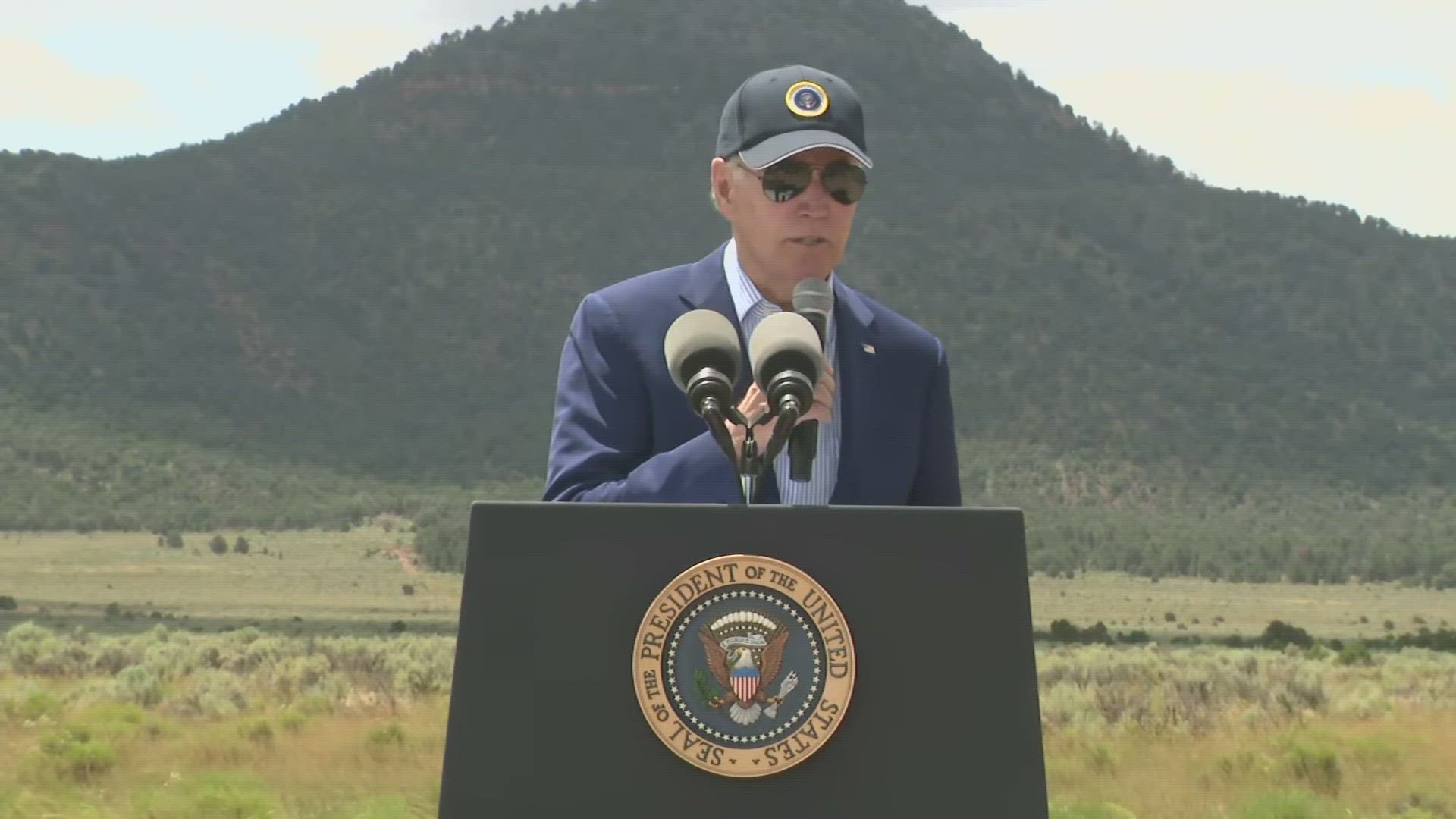

ARIZONA, USA — It was no secret that Arizona was built on mining, and at great cost to indigenous communities. But times are changing, and during his upcoming visit, President Biden designated a vast swath of land near the Grand Canyon as a national monument -- a move that would render it off-limits to uranium mining.

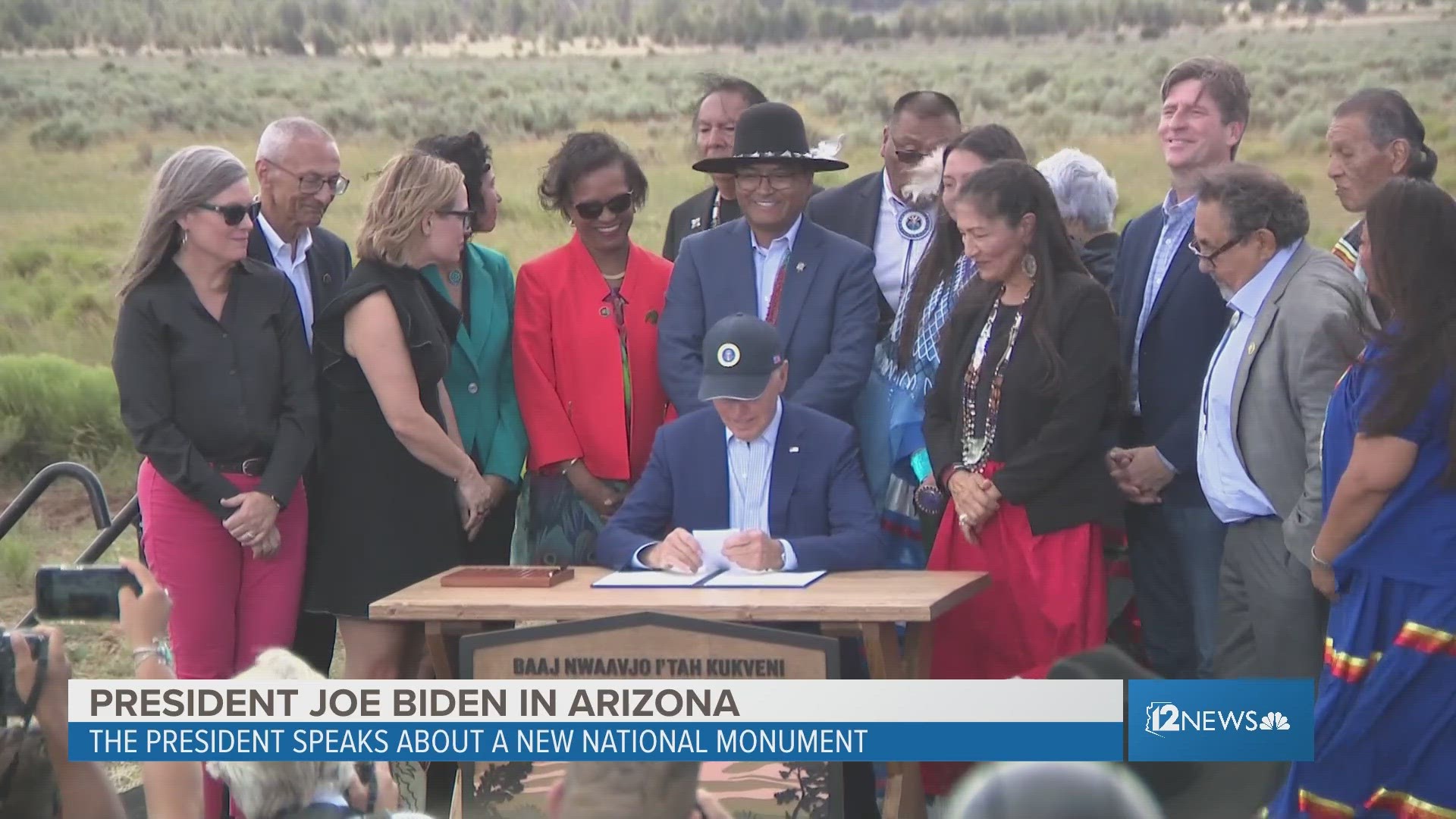

The Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni -- Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument sets protection standards for 917,618 acres of land in three distinct areas north and south of Grand Canyon National Park. The new monument contains over 3,000 known cultural and historic sites. It also designates 12 indigenous tribes associated with the canyon to help oversee the protected land.

Tribal leaders in Arizona have been leaning on the federal government for this designation, urging Biden to use the Antiquities Act to create the monument. Conversely, lawmakers like Rep. Paul Gosar and private land ranchers oppose the decision, citing a potential loss of land stewardship and water rights in the area.

"Today’s designation recognizes and is a step toward addressing the history of dispossession and exclusion of Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples in the area, including that occurring when the federal government established the Grand Canyon Forest Reserve in 1893, Grand Canyon National Monument in 1908, and Grand Canyon National Park in 1919," the White House announced in a press release.

Here's a look at what the monument will mean for the state:

Precedence for the new national monument

This won't be the first time a national monument has been created next to the Grand Canyon National Park. In 2000-2001, former President Bill Clinton created four national monuments in and around Arizona -- two of them near the canyon.

Using the 1906 Antiquities Act -- which allows presidents to protect land by claiming them as national monuments -- Clinton created the Agua Fria National Monument near Black Canyon City, the Grand Canyon-Parashant and Vermillion Cliffs national monuments in the Arizona Strip, the Ironwood Forest National Monument near Tucson and the Sonoran Desert National Monument south of Interstate 8 near Casa Grande.

The move caused a stir with state Republicans, who alleged that Clinton bypassed Arizonan voters to create the monuments, the Washington Post reported. However, the monuments kept their status after a 2017 executive order from then-President Donald Trump forced a review.

Given the legal resilience of Arizona's protected lands, such a designation from President Biden is likely to stand against challenge.

Biden names new Grand Canyon national monument to protect land

How's this different from the Grand Canyon National Park?

Arizona is home to 18 national monuments, more than any other state. Alongside our national parks and historic trails, Arizona has huge amounts of protected land aimed at preserving our natural features. But how is the new Grand Canyon National Monument different from the existing national park?

In general, national parks contain a variety of resources and encompass large areas of land and water to protect those resources, according to the National Park Service website. National monuments are usually smaller, and are focused on protecting nationally significant resources. They also tend to be less developed than national parks.

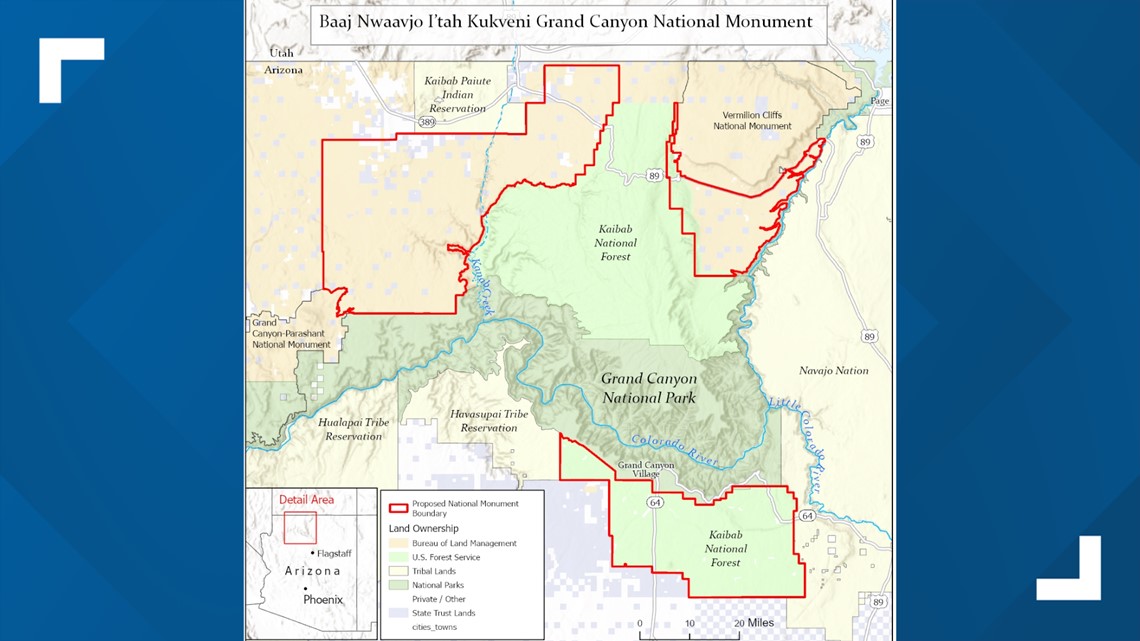

The original proposal for the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni Grand Canyon National Monument was roughly 1.1 million acres, almost the same size as the ~1.2 million acre Grand Canyon National Park.

According to the White House, the official monument will cover 917,618 acres of land in roughly the same proposed areas.

>>Editor's note: The map pictured below is a proposed boundary for the monument, and may not reflect official borders.

The monument will be split into three areas shouldering the north and south edges of the park, and in places would extend as far north as the Arizona-Utah border. It nearly doubles the amount of protected land surrounding the Grand Canyon near the Navajo Nation, as well as the Havasupai, Hualapai and Kaibab Paiute reservations.

Impact on indigenous communities

Even the monument's name is significant. Baaj Nwaavjo means “where tribes roam” to the Havasupai, and I’tah Kukveni means “our footprints” to the Hopi. Much of the land that the monument would protect is considered sacred and holds generational significance to the tribes that call the area home.

“As guardians of the Grand Canyon, we have a duty to protect it,” said Edmond Tilousi, the vice chairman of the Havasupai Tribe. Several tribal leaders discussed why the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River have spiritual, historic, and cultural meaning for their people.

Designating the area as a national monument would make a 20-year mining moratorium in the area permanent, which advocates say would halt a "toxic legacy" of health, safety, and environmental damage to local communities in the area.

The monument would also turn stewardship and care of the protected land back over to tribes represented in the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition.

The Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition is comprised of the Havasupai Tribe, Hopi Tribe, Hualapai Tribe, Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, Las Vegas Band of Paiute Indians, Moapa Band of Paiute Indians, Navajo Nation, Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni and Yavapai-Apache Nation.

What's the risk of uranium mining?

Uranium is a metal that exists naturally in the earth. It fuels nuclear power plants, runs nuclear reactors in naval ships and submarines, and is involved in production of medical, industrial and military products. Miners extract uranium from open pits and underground.

Contact with uranium is associated with cancer risks. The topic is especially sensitive to the Navajo Nation where uranium mining during the Cold War poisoned soil, water and rocks, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Supporters of uranium mining in northern Arizona say extraction methods used today would not pose contamination risks as they did decades ago. There was also debate Monday about whether the proposed national monument, several miles from the Grand Canyon at its nearest point, would do anything to prevent contamination of the Colorado River watershed.

According to the World Nuclear Association, about two-thirds of the world’s production of uranium comes from mines in Kazakhstan, Canada and Australia. The U.S. imports nearly all of its uranium. Advocates of uranium mining in the U.S. say it is a national security issue.

Pushback from local groups

Overall, the monument has received an outpouring of support from lawmakers and community members alike. However, some local stakeholders have pushed back on the proposal.

At a July public hearing, several ranchers from the Arizona-Utah border expressed concern the move is an overreaction by the federal government. They worry they will lose stewardship of federal lands leased for grazing or lose water rights.

“The move represents the Biden administration’s latest massive land grab and would be devastating to Mohave County,” said a representative of Congressman Paul Gosar.

Chris Heaton, a 6th generation rancher near Kanab, Utah, said a map of the proposal suggests he would lose private land. However, national monuments can only be created from federal land and are often created from national forests and BLM lands, meaning actual private land would be unaffected.

At this time, the government has not disclosed the acreage and borders of the monument should the designation go through. Maps have been provided by advocates for the proposal.

Arizona Politics

Get the latest Arizona political news on our 12News YouTube playlist here.