The fault running for more than 600 miles off the coast of Washington, Oregon, Northern California and Vancouver Island, Canada is more complex than first thought, according to new research from the University of Oregon.

“Our study doesn’t address the when question, but does address where it might start occurring,” said Doug Toomey, professor of Earth Sciences. "And it’s most likely to occur where the fault is more strongly locked.”

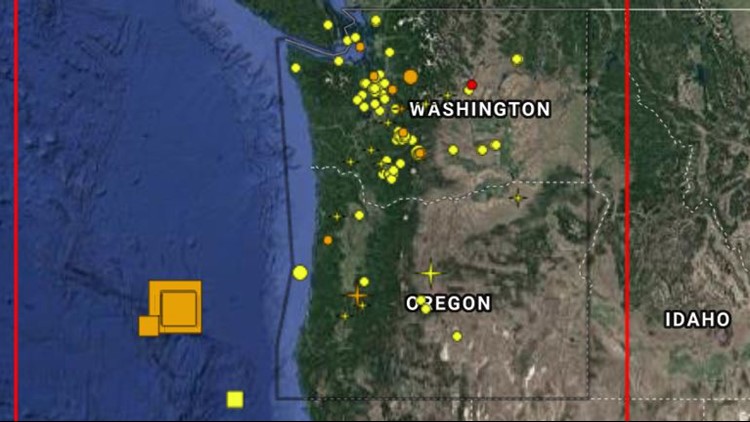

Toomey, Ph.D. student Miles Bodmer, and a University of Oregon team set out seismometers, many of them on the continental shelf underwater, to try and image what the Cascadia Subduction Zone looks like deep inside the earth. The fault begins at the edge of the continental shelf.

The Cascadia fault is what is known as a subduction zone. Subduction exists around the Pacific Rim and other parts of the globe. It happens because the ocean floor is made up of crustal plates, ocean plates that are forced underneath the continental plates. Often, like in the Pacific Northwest, those plates are locked together. When enough pressure builds up, the plates suddenly slip past each other creating the earthquake and usually a large tsunami.

Scientists expect the next quake on the Cascadia Subduction Zone to reach a magnitude 9.0 or more and could last more than five minutes.

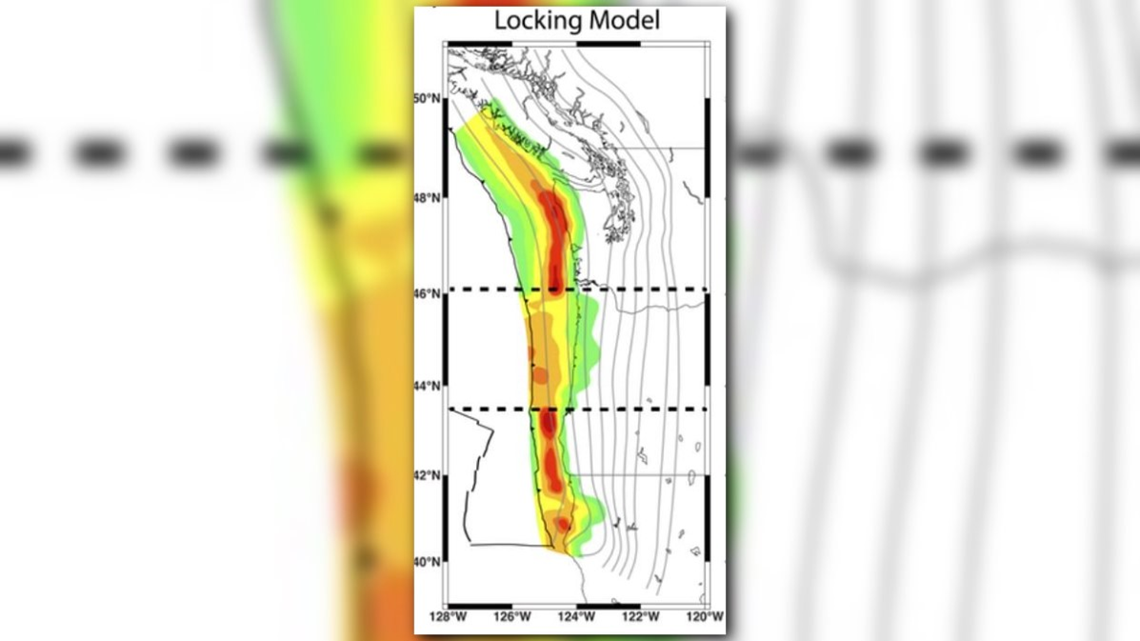

It’s the pattern of this locking that is at the core of the University of Oregon research. It’s not the same everywhere, it’s in three distinct segments.

“It’s important for your viewers to realize that this is not news that says it’s worse than we thought it was, but it’s simply to understand how it’s split up into three segments and why some segments are more locked than others,” said Toomey.

That may indicate where the rupture might be more likely to begin, at the northern end along Washington’s coast, or the southern end between Cape Mendocino, California where the fault begins and off southwestern Oregon, areas where the research has found more locking between the plates.

One question raised by the research -- would the entire length of the fault unzip in one giant earthquake, or would different segments rupture independently, years apart…a theory called a “decade of terror?”

“We don’t know if it goes in one, two or three segments,” said Toomey. “And what our research shows is why there are three segments there. And whether it’s a decade of terror or one segment that goes, we don’t know the answer to that yet.”

Toomey advocates for a permanent network of seismometers on the continental shelf to watch under the ocean, as seismometers and GPS stations do on land, the movement of the various plates.

He said a more complete picture of plate movement could give scientists a much better idea of just when a quake becomes more likely, and contribute to the new ShakeAlert earthquake early warning system; which could provide minutes of notification to inland areas when a quake starts and how quickly the shaking will arrive.