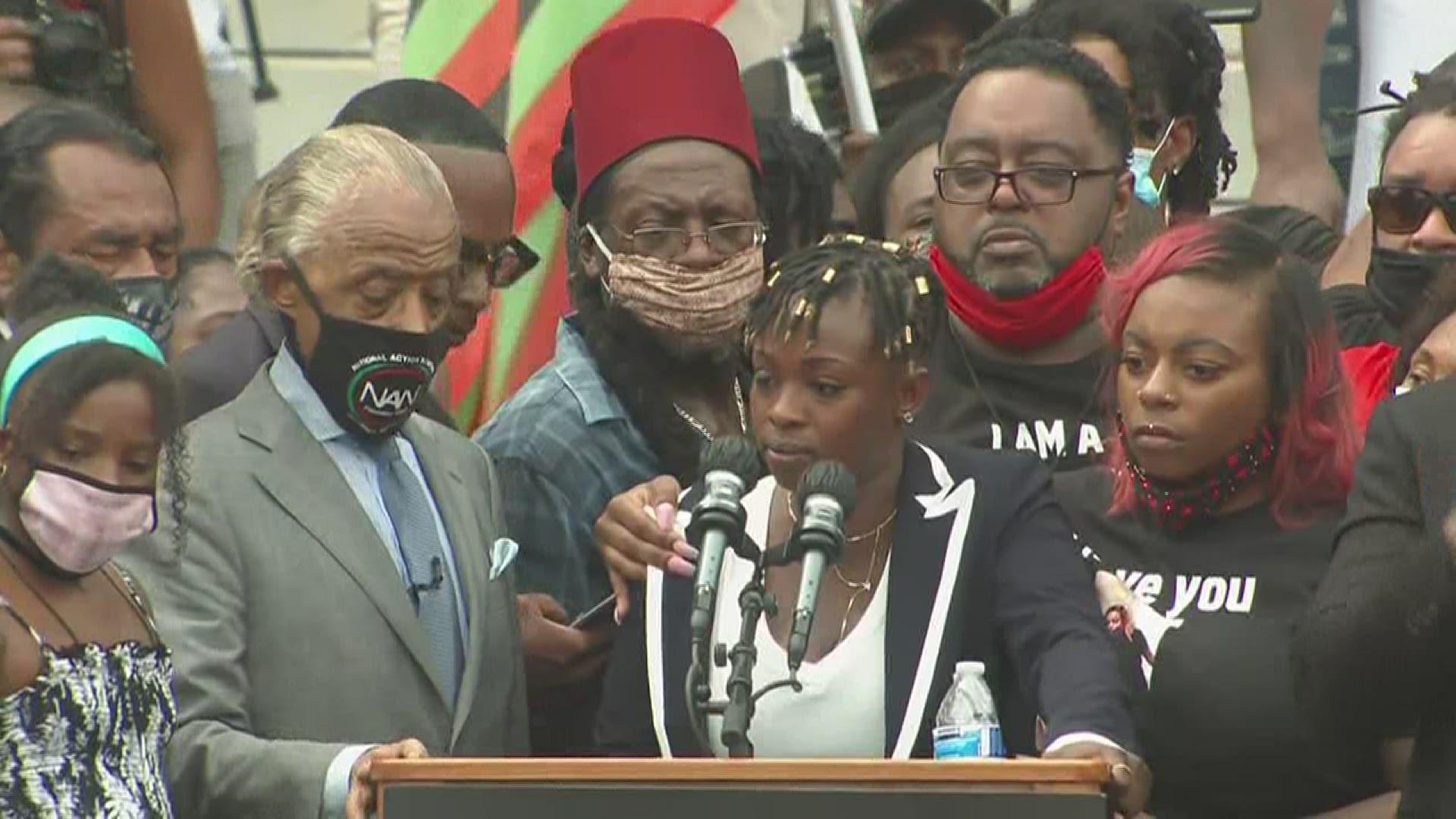

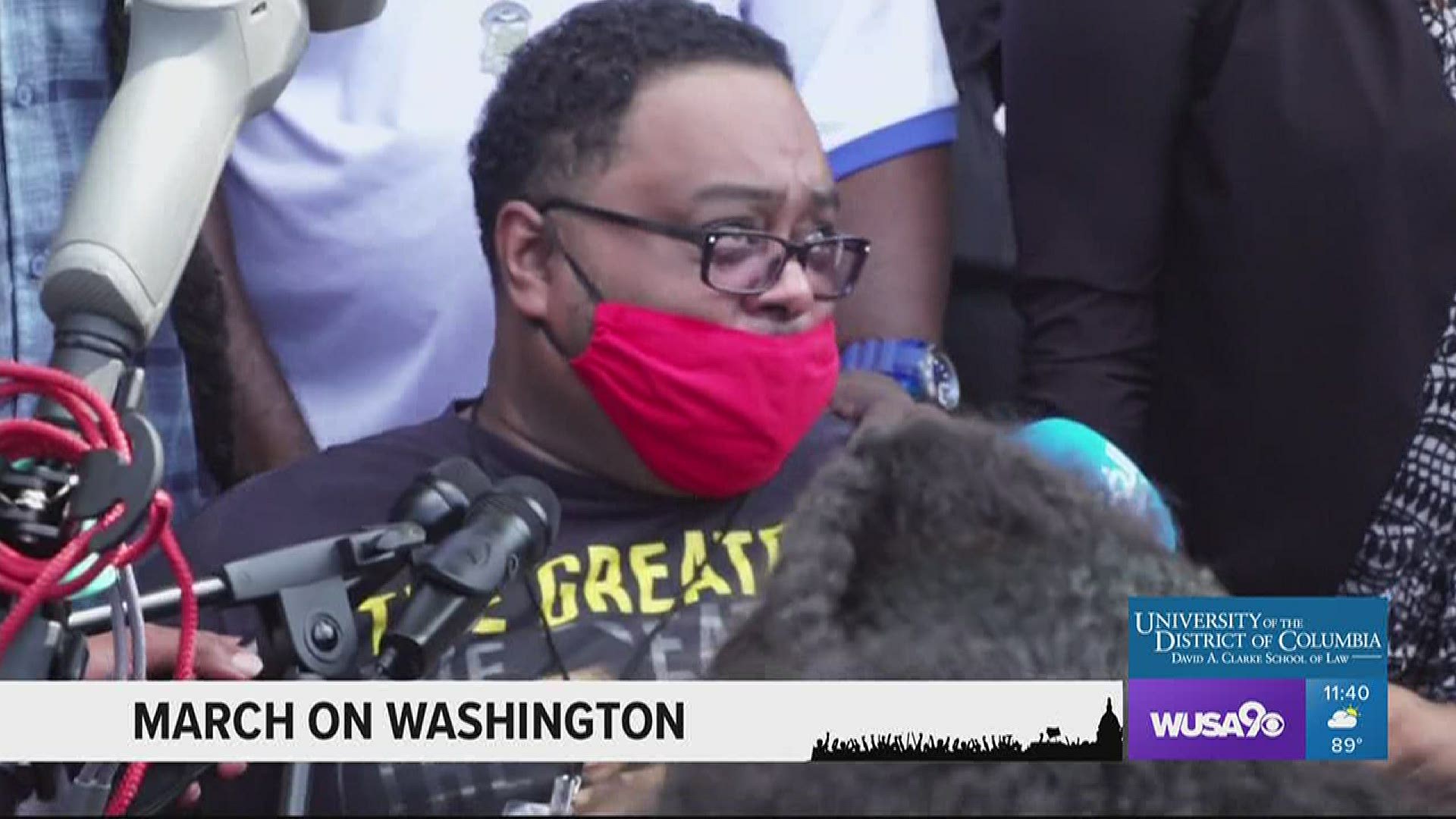

MADISON, Wis. — Editor's note: The attached video is from the 2020 March on Washington featuring remarks from Jacob Blake's sister.

The Kenosha police union on Friday offered the most detailed accounting to date on officers' perspective of the moments leading up to police shooting Jacob Blake seven times in the back, saying he had a knife and fought with officers, putting one of them in a headlock and shrugging off two attempts to stun him.

The statement from Brendan Matthews, attorney for the Kenosha Professional Police Association, goes into more detail than anything that's been released by the Wisconsin Department of Justice, which is investigating.

The Sunday shooting of Blake, a Black man, put the nation’s spotlight on Wisconsin and triggered a series of peaceful protests and violence, including the killing of two people by an armed civilian on Tuesday. Blake is paralyzed from the shooting, his family said, and recovering in a Milwaukee hospital.

Cellphone video shows Kenosha Police Officer Rusten Sheskey and another officer following Blake with their guns drawn as he walks around the front of a parked SUV as they responded to a domestic dispute.

According to Matthews, the officers were dispatched there because of a complaint that Blake was attempting to steal the caller’s keys and vehicle. Matthews said officers were aware that Blake had an open warrant for felony sexual assault before they arrived.

Blake was armed with a knife, but officers did not initially see it, Matthews said.

“The officers first saw him holding the knife while they were on the passenger side of the vehicle,” he said.

The bystander who recorded the shooting, 22-year-old Raysean White, said he saw Blake scuffling with three officers and heard them yell, “Drop the knife! Drop the knife!” before gunfire erupted. He said he didn’t see a knife in Blake’s hands. State investigators have said only that officers saw a knife on the floor of the car. They have not said whether Blake threatened anyone with it.

Matthews said officers made multiple requests to Blake to drop the knife, but he was uncooperative. He said officers used a Taser on Blake, but it did not incapacitate him.

“Blake forcefully fought with the officers, including putting one of the officers in a headlock,” Matthews said. A second stun from a Taser also did not stop him, he said.

As Blake opened the driver’s door of the SUV, Sheskey pulled on Blake’s shirt and then opened fire. Blake’s three children were in the backseat.

“Based on the inability to gain compliance and control after using verbal, physical and less-lethal means, the officers drew their firearms,” Matthews said. “Mr. Blake continued to ignore the officers’ commands, even with the threat of lethal force now present.”

The Wisconsin Department of Justice had no immediate comment on the union's version of events. An attorney for Blake's family did not immediately respond to emails seeking comment.

The state agency has released almost no information about Sheskey or the other two officers, Vincent Arenas and Brittany Meronek.

An annual Kenosha Police Department report indicates Sheskey was hired as an officer in 2013.

In an August 2019 interview with the Kenosha News, Sheskey said he had always wanted to go into law enforcement, noting that his grandfather served the city as a police officer for 33 years.

“What I like most is that you’re dealing with people on perhaps the worst day of their lives and you can try and help them as much as you can and make that day a little bit better,” Sheskey told the newspaper. “And that, for the most part, people trust us to do that for them. And it’s a huge responsibility, and I really like trying to help people. We may not be able to make a situation right, or better, but we can maybe make it a little easier for them to handle during that time.”

Sheskey, who appears to be white based on photographs and video, was moved to the bike patrol in 2017, according to the Kenosha News interview.

He was among a group of officers named in a handwritten federal lawsuit filed last year by a man in the Kenosha County jail, Lathan Steven Ward, who accused the officers of damaging his door while they were breaking it down to execute a no-knock warrant in August 2018. He also accused the officers of racial profiling and causing him pain and shame. U.S. District Judge J.P. Stadtmueller dismissed the case, ruling Ward’s allegations weren’t sufficient to sustain the lawsuit.

Before Sheskey joined the Kenosha Police Department he worked for the campus police department at University of Wisconsin-Parkside in Kenosha from the fall of 2009 to the spring of 2013. He served in various roles, including as a dispatcher, enforcing parking regulations and as a police officer, university records show.

Investigators have not said how many complaints may have been filed against Sheskey, whether his superiors ever disciplined him or whether he earned any commendations.

Arenas has been with the Kenosha Police Department since February 2019 and previously served with the U.S. Capitol Police Department from June 2017 through January 2019, authorities said. Arenas served in the Marines from 2012 to 2017 and did not do any combat deployments, the Marine Corps said.

Meronek joined the Kenosha police force in January. She received a technical diploma from the criminal justice law enforcement academy at Gateway Technical College in May, according to school records.

The Associated Press has filed a request under Wisconsin’s open records law with both the state Department of Justice and the Kenosha Police Department for the officers’ service records. Government agencies typically take weeks or months to turn over documents in response to such requests.

Sheskey and Meronek did not respond to emails sent to possible addresses for them and Arenas did not return a phone message left at a possible phone number for him. No one returned messages left at possible telephone numbers for officers’ family members. No one answered the door Thursday at Sheskey’s home.

___

Associated Press reporters Stephen Groves in Kenosha, Scott Bauer in Madison, Wisconsin, Amy Forliti in Minneapolis and researchers Monika Mathur in Washington, D.C., and Rhonda Shafner in New York contributed to this report.