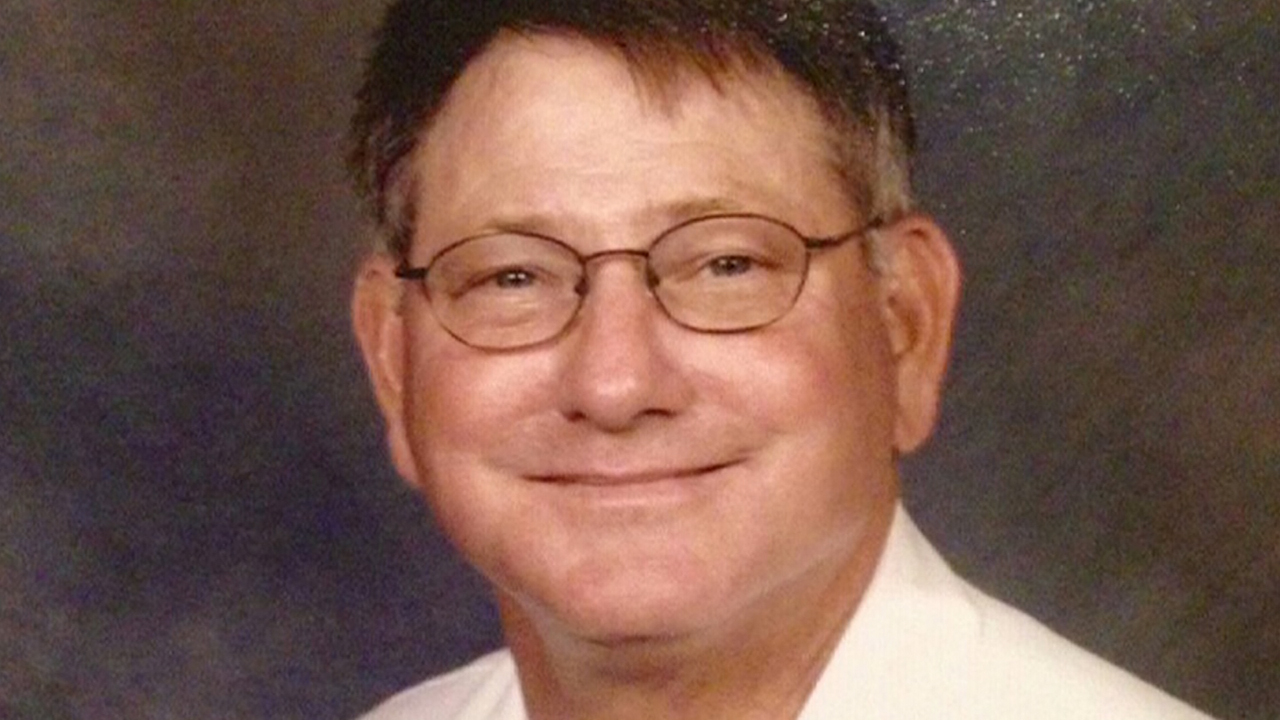

MCKINNEY, Texas — A longtime McKinney family doctor, trusted for three decades by many families with their health, stands accused of using his prescription pad as a license to deal drugs.

The Drug Enforcement Administration has linked Dr. Randall Wade to the deaths of at least six patients, according to court records obtained by News 8.

The DEA and federal prosecutors say Wade was running a pill mill and prescribed massive amounts of powerful painkillers to patients who didn’t need them.

Wade, 65, was indicted last month on drug distribution charges in the Eastern District of Texas. Last month, U.S. Magistrate Judge Christine Nowak concluded that Wade posed a potential danger to the community. She ordered that he be held, pending trial.

Wade’s attorneys are seeking to convince the judge to reverse her decision. A hearing is scheduled for Thursday morning.

“You didn’t have to steal a prescription pad from him,” said Dedra Hogan, whose daughter, Brittany, was one of the six deaths mentioned in a recent court hearing. “He wrote it out for you.”

Brittany died in 2015 in the back seat of her car of a heroin overdose in Princeton, Texas. Tests also found Xanax in her system. She was 26 years old.

Her family says Brittany got hooked on heroin after being prescribed large doses of powerful opiate-based drugs by Wade.

“Everybody in town knew Dr. Wade,” Dedra Hogan said.

Brittany Hogan, who had worked a dog groomer, was a recreational drug user until she began seeing Wade several years ago. Wade prescribed her hydrocodone and Xanax.

“He would say every day without pain is a good day,” said her mother, a former patient of Wade’s.

Her mother says Brittany was getting so much of it that she began selling it, and it helped fund the drug-fueled lifestyle her daughter was living.

Brittany’s grandfather, Jerry West, tried everything he could to get Brittany off drugs.

“Finally, I said, 'God. it's in your hands,' and that was right before she passed,” he said.

Federal prosecutors say Wade was repeatedly warned to change his prescribing practices: by the medical board, by the coroner’s office, by the DEA and by pharmacists, court records reveal.

“He won’t stop,” federal prosecutor Heather Rattan told a judge in a recent hearing. “He hasn’t stopped.”

By the time of his Oct. 17th arrest in his office parking lot, Dr. Wade been under investigation for nearly a year. During that time, the DEA posted a camera on a pole outside his clinic. Agents followed him to his mansion in his gated McKinney neighborhood.

At a detention hearing in Sherman the day after his arrest, federal prosecutors DEA Agent Susannah Herkert testified that the DEA began receiving complaints about him as far back as 2012.

Wade was among the top prescribers of hydrocodone in a 10-county area for 10 months of last year, she said.

Eighty-eight percent of the drugs – hydrocodone, alprazolam (Xanax) and carisoprodol (the muscle relaxer Soma) – he prescribed are three of the most abused drugs on the market, the agent said. They're referred to as a “holy trinity” for the euphoric high they give users.

“This is highly unusual to see a family doctor prescribing these three drugs, three of the most abused controlled substances,” Herkert said.

Pharmacies began refusing to fill his prescriptions, the agent said.

A pharmacist at Dyer Drug told the DEA he had to run off patients of Dr. Wade in late 2015 because it “appeared to him that they were not using the drugs for legitimate medical purposes.”

“The pharmacist told me that he called Dr. Wade about his concerns and that Dr. Wade told him that he did not think it was a problem and that Dr. Wade told him he was doing what his patients wanted,” Herkert said.

A Kroger pharmacist told Herkert that she called Dr. Wade about one young patient and he told her to tell him that he was a drug addict. When she asked Wade if she wanted her to cancel the remaining refills of Xanax, she said he told her no.

CVS and Target also blocked prescriptions from Wade, the agent said.

Herkert said she interviewed a former employee, who said that Dr. Wade blamed the overdose deaths of his patients on “patients for abusing the drugs and not using it as directed.” The former employee told Herkert that there were “mules” who brought in patients from the Gainesville area to get the drugs.

The agent testified that Wade continued on as before even after the Texas Medical Board cited him last June for running an unregistered pain clinic and overprescribing to 17 patients "without stating a clear medical rationale."

The medical board ordered him to send his current pain patients elsewhere within 180 days and to take no new ones. If he didn't comply, his license would be suspended.

DEA agents raided Wade’s home and office on Sept. 13. They confiscated about 1,000 patient files. Many of his patients were driving long distances, and there is little documentation for why he was prescribing the drugs, the agent said.

“We consistently see page after page of refill, refill, and refill,” Herkert said.

An outside medical expert hired by the DEA reviewed a sampling of the files and determined Wade he was prescribing without a legitimate medical purpose, the agent said.

The indictment specifically links Wade to the death of Lowell Haynes, who went to Wade on April 3, 2015 for a thorn in his hand. Wade prescribed pain medications for it.

Haynes filled prescriptions for hydrocodone and alprazolam (Xanax) at Dyer Pharmacy in Farmersville that same day. He was found dead by his brother the next day in Princeton.

The autopsy results showed he died from the "toxic effects of hydrocodone and alprazolam.”

The DEA outside reviewed Haynes’ file and concluded that he was given “high-risk medications” without documentation to back up why he prescribed it, according to court transcripts.

Herkert said she interviewed Dr. Wade on the day they ran the search warrant.

She said he talked of the numerous back and neck surgeries he had had. She said he denied taking hydrocodone for pain and stated, “I don’t take none of that. I won’t touch it because it affects my mind. If I can’t work, I lose my license.”

She said he acknowledged that pharmacies were refusing to fill his prescriptions and said, “If I could find a lawyer, I’d sue the hell out of them.”

Herkert said when she asked him to voluntarily turn over his controlled substances privileges, he refused the request.

In the weeks it took obtain an indictment, Wade was still seeing patients. Another of Wade’s patients would die just days before his arrest, the agent testified.

On Oct. 12, Netoche Fair was found dead on a park bench in Greenville. She had Xanax and hydrocodone pill bottles with his name on them in her car. Her autopsy is pending.

Once they arrested him, he was combative and aggressive, the agent said. She testified that he grabbed a syringe and displayed it in a threatening manner at a U.S. Marshal and had to be put in hand restraints.

The doctor's wife also took the stand at that hearing in an effort to convince the judge to release him. She said he was a diabetic and said that sometimes he would act combative and irrational when his blood sugar gets low.

“Everybody knows him as a down-to-earth family doctor,” said his wife, Sharon Lippincott-Wade. “He wears cowboy boots. Everybody always says how he easy he is to talk to.”

She denied he was running a pill mill and said he genuinely cared for his patients. Lippincott-Wade said they have a 13-year-old son and that her husband is the sole wage earner.

“This man is a workaholic,” she said. “He’s never taken me on a honeymoon and we’ve been married for 16 years.”

Wade's arrest and indictment is an answer to prayer for Brittany Hogan’s family.

In the days before her daughter died, her mother says she desperately worried about her daughter. So she gave her this worry box to put her problems in.

“I gave her that box and told her I love you,” Dedra Hogan saids. “I looked at her and I said, ‘I can’t keep on.’”

It wouldn’t take long before a mother’s worst fear would come true.

“Five days later, I get the call,” she said. “That was my last conversation with her.”