PAGE, Ariz. — Lake Powell stores an incredible amount of water. It snakes its way through sandstone canyons from Arizona far up into Utah, and has more coastline than the entire West Coast of the United States.

And it’s a crucial stop for water on its way to the Southwest, where Arizona, Nevada and California all draw on it for drinking and farming.

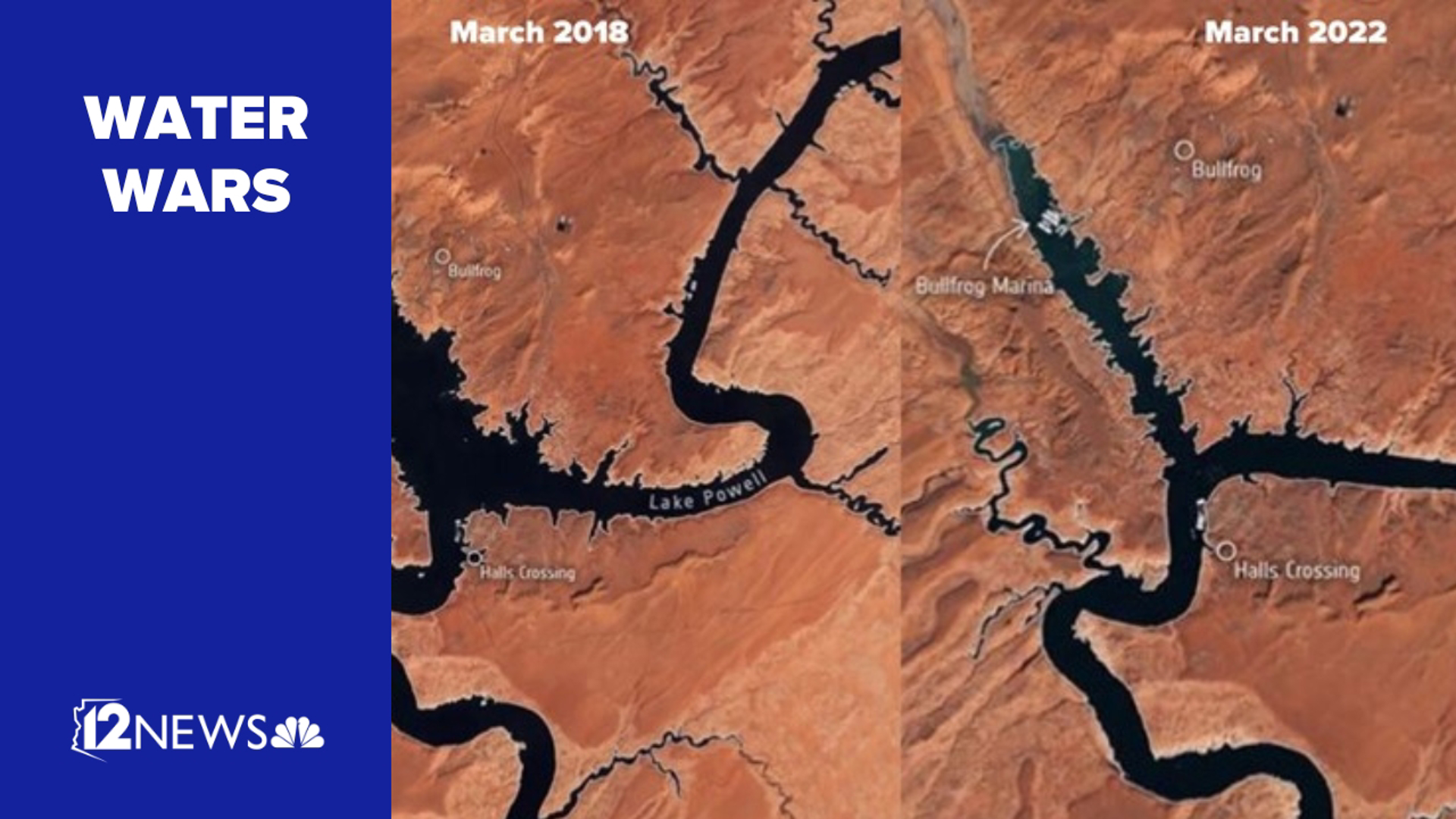

But Lake Powell reached its lowest point ever earlier this year and the Bureau of Reclamation is drawing on water from other reservoirs and limiting the amount of water released through Glen Canyon Dam to keep the lake at a safe level.

Some of those canyons have run dry, and beaches that led to the water now stop far above it.

See a nearly 40-year timelapse of Lake Powell's dry-up from Google Earth here:

Power generation through Glen Canyon Dam is also down, though the dam is still producing power. If the water level continues to fall, the dam could potentially stop producing power in the coming years.

So instead of moving water around, hoping to keep the lake level steady and the power plant running, what if Lake Powell just didn’t exist?

Could we drain Lake Powell?

“We're reaching a point where this structure might turn into more of a liability than an asset,” Eric Balken with the Gen Canyon Institute said, looking over at Glen Canyon Dam.

Balken thinks a radical solution may be the best solution.

If the lake was drained and the water was sent downstream to Lake Mead, it may end up saving more water in the long run.

“We need to start thinking about life beyond Lake Powell,” Balken said. “The Bureau of Reclamation is going to extreme measures to prop up this reservoir. Even with these extreme measures being taken, this reservoir is still going to be running a deficit.”

The plan is this: open all the valves at the dam and let the water run out. The lake would drain downstream through the Grand Canyon and end up in Lake Mead, which is also at its lowest level in history.

The water would fill Lake Mead, which is the last stop before it’s diverted to the Southwestern states.

Since Lake Powell is primarily sandstone, the lake actually leaks water into the porous rocks. Balken said depositing the lake’s water in Lake Mead, which isn’t made out of sandstone, would actually save water.

“The estimation is around 30,000 to 50,000 acre-feet per year,” Balken said.

That’s not a large amount of water in the grand scheme, though it’s the amount of water about 150,000 households would use in a year. It’s also about 10% of the water that Nevada gets from the lake.

The lake would also revert to its “natural state," the state it was in before the dam was built. Instead of a winding lake, there would be miles of winding canyons.

“This dam was built to harness excess water and there is no more excess water,” Balken said. “There's just not enough water in the system.”

'All ideas need to be on the table'

It sounds a little crazy.

However, experts say nothing is really crazy at this point in the West’s 22-year drought.

“When that idea was first being shopped, people thought that was like a way out there notion.” Sarah Porter with the Morrison Institute for Water Policy said. “But at this point, I would say that all ideas need to be on the table.”

Porter's reasoning is that all the other ideas to increase the amount of rain and snowpack are equally “out there."

“Wrangling clouds, towing icebergs, an intermittent floodwater pipeline,” Porter said. “Most of these are feasible from an engineering standpoint, but that doesn't mean that they are that they're a good option.”

There are definite downsides to getting rid of the lake.

For one, Glen Canyon Dam produces power for 5 million people. Without the dam, the power grid would need to make that up somewhere. The power plant also acts as a stopgap for high power demand.

The town of Page also gets its water from the lake, creating another problem that would have to be solved.

Balken admits there are hurdles to the idea and opposition from a lot of sources. But, the water levels continue to drop and there’s no silver bullet to fixing it.

“Regardless of whether you are for or against Glen Canyon Dam or Lake Powell,” Balken said, “it doesn't matter. These changes are happening and we need to make the most of it.”

RELATED: 'The nature of the beast': The numerous ways Arizona's megadrought will affect people's health

Water Wars

Drought, wildfires, heat and monsoon storms: Arizona has seen its fair share of severe weather. Learn everything you need to know about the Grand Canyon State's ever-changing forecasts here.