ARIZONA, USA — Editor's note: The above video aired during the first Colorado River water cuts in 2021.

If you want to reach San Diego's sparkling blue ocean from Phoenix, you will first have to navigate a sea of brown shades along Interstate 8. Desert dust the color of Dad's weekend khaki cargo shorts. Rocks covered in dark brown desert varnish. Trees dried out to the bleached-out brown of a Kansas wheatfield.

The beige landscape has occasional dots of green where dry streams have coursed wet. Until you hit Yuma Valley: an Emerald City.

Yuma County's farms are known as the "Winter Salad Bowl Capital," producing a majority of the country's lettuce, spinach and cabbage crops during the cold months. The area isn't some kind of mythical Eden; the crops need a sizable water supply to stay crisp and fresh in Arizona's arid heat.

And in that way, the farms are the main stage in the fight against the West turning to dust because of drought.

Experts are predicting a "catastrophe" for the farms ahead of a Bureau of Reclamation water cut announcement. Local officials are scrambling to find solutions as the future cuts and worsening drought endanger the area's crop production, with best-case scenarios predicting many small farms still going out of business.

Yuma failing wouldn't just be a hit to Arizona. State agriculture experts said the nation as a whole would have to rebuild its modern foodways if the area's farms dry up.

Yuma to be the "low hanging fruit" for water supply

The Bureau of Reclamation told Southwestern states in June they would each have to figure out how to cut two to four million acre-feet of Colorado River water from their supply next year.

The bureau said states had to come up with a plan by mid-August, or federal officials would enforce restrictions. The deadline has come and gone. Experts predict officials will announce the drastic cuts by year's end.

"In order to get to the volumes of water experts are saying we need to leave in the system, water has to come from agriculture," Kyl Center for Water Policy Director Sarah Porter said.

Arizona's farmers weren't surprised by the announcement, but they were frustrated.

PREVIOUS COVERAGE: Arizona's cities may see 'huge' water cutbacks soon. Here's what that means for Valley residents

"We continue to be frustrated by the lack of collaboration between all of the lower basin states, especially California, in trying to share some of the pain of the shortage," the Arizona Farm Bureau's Director of Government Relations Chelsea McGuire said.

Arizona has been hit with the majority of river water cuts since the first Lake Mead water shortage was declared last August. The cuts largely lowered the river water supply of growers in central Arizona.

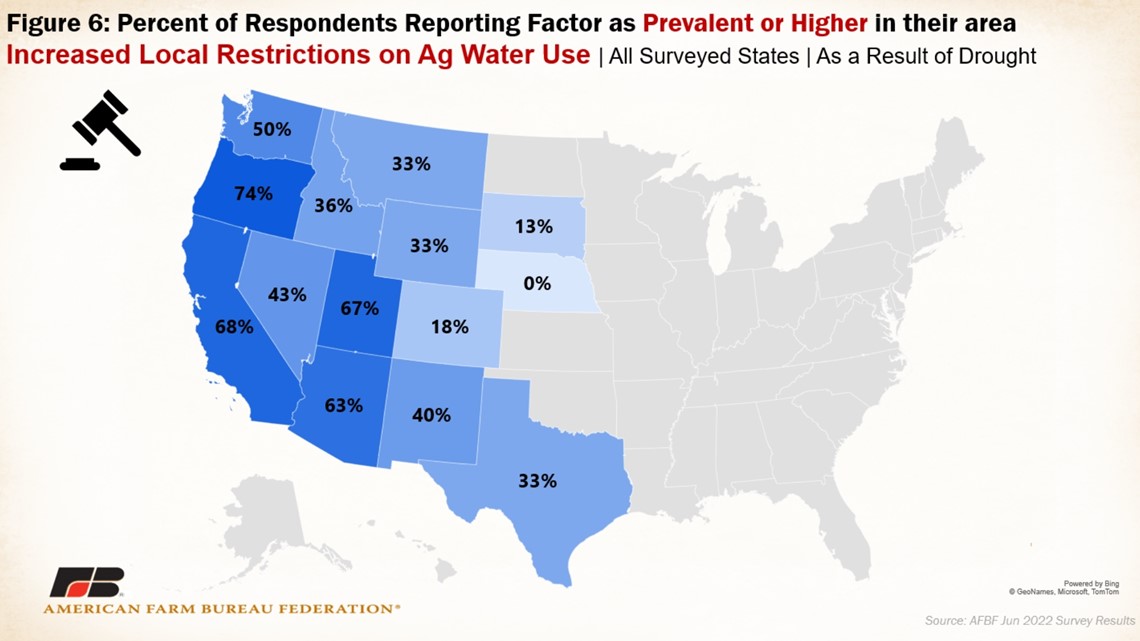

The rest of the state's farmers took this as a sign they should start preparing to have less water, with a recent survey from the American Farm Bureau Federation showing more than half of Arizona's farmers rely more on groundwater and are facing increased local water restrictions.

COVERAGE OF THE TIER 1 SHORTAGE: Feds declare water shortage for Colorado River, cut allotment to Arizona

"Agriculture is going to have a target on its back...it's kind of the low-hanging fruit in a lot of people's minds for where to take water from when it's needed," McGuire said.

Around 74% of Arizona's Colorado River water supply goes toward agriculture. The fact has been used to justify the target on the sector's back.

But, Arizona's Agribusiness and Water Council Executive Director Chris Udall said that amount is in line with global arid farm water-use standards.

"That number is worldwide," Udall stated. "That's because we have to grow food to survive."

Officials expect the cuts will mainly affect Yuma farms as the Bureau of Reclamation's announcement looms, since the area is one of the biggest river water users in the state.

The water usage numbers don't lie, but large water cuts to Yuma would have numerous consequences, both for Arizona and the entire nation.

The U.S. would have to create a "completely different food system" if Yuma goes away

The expected cuts are only the first of Yuma's problems. The community would face a disaster if river water levels reach dead pool status: when water levels in reservoirs drop below the point of being able to flow downstream.

"Dead pool for Yuma, and for other communities and farmers along the river, would be a catastrophe. That means no water," Porter said.

The "catastrophe" wouldn't just be limited to Yuma County, but would extend to the whole of the United States' food production.

Yuma farms are a national leader in produce production, especially during the winter months when the vast majority of the U.S. is faced with temperatures too cold to grow.

The lack of Yuma cold, combined with Arizona's year-round sunshine and robust water infrastructure, has allowed leafy greens to prosper during the winter months.

"From November to March every year, the lettuce, broccoli, cauliflower and other leafy green production we depend on as a nation are coming out of the lower Colorado River Valley for about 95% of the country," said Jeffrey Silvertooth, an agronomist and professor at the University of Arizona.

Yuma's climate is so advantageous that the nationwide food system has practically been built around it.

"The issue isn't where we're going to find our lettuce if Yuma fails. The real issue is that there's nowhere we could go to replace that kind of winter vegetable production," Porter said. "There are very few places on Earth that offer what is available in Yuma."

See all the crops that would be affected on page seven of Arizona's leafy greens report here:

If Yuma farmers can't find another source of water when they lose the majority of their Colorado River allocation, the U.S. will have to find a different way to get its veggies during the winter.

"If we no longer have a thriving produce industry in Yuma, not only do Arizonans not have access to winter leafy greens, but the entire nation would lose that access as well in the winter and spring," McGuire said.

"Prices will increase, availability will decrease. It'll be a completely different food system than what we're used to."

Farmers are fighting to stay afloat

Desert farming can create conflict over water. In his decades-long service to Arizona agriculture, Silvertooth has seen a kind of water paranoia get the better of some farmers, with accusations of water stealing being hurled at neighbors.

This water crisis, however, has created more cooperation between Arizona's farmers, rather than competition.

"Some tough negotiations have gone on and the farmers have hammered out a plan to cut as much water as possible for the farms to stay alive," Silvertooth said.

The plan, outlined in Udall's recent letter titled "Save the Colorado River," suggests a drastic, but agreed-upon, compromise.

"Farms totaling 925,000 acres of farmland will try and stay in business by using an acre-foot less of water on their farms for a four-year period, which is quite a cut," Udall said. "Some farmers have penciled it out and said 'I can't do more than that or it's curtains'."

The farmers won't be going through this restriction for free. They've said that in order to do this, they would need to be compensated $1,500 per acre-foot of water by the federal government.

So far, they have not heard back from the Bureau of Reclamation.

Changing water rights may be the last-ditch effort

Udall mentioned that while farmers wait for the bureau's response, it would be nice to see some city amenities get cut before state necessities.

"We would prefer seeing less water cut for food production and maybe see less swimming pools and grass lawns," Udall said.

The idea sounds easy enough on paper, but is much harder to achieve in the real world due to how Arizona's water rights are set up.

Arizona's agriculture industry has had a troublesome history of overusing water. Before using Colorado River water, farmers relied on groundwater and almost drained the state dry. The crisis was seemingly averted in 1973 with the formation of the CAP canal.

The overuse of well water led to farmers giving up their CAP rights to cities in exchange for those cities subsidizing the water through urban property taxes.

State water rights weren't the only rights causing frustration among Arizona's farmers. McGuire had numerous people tell her they were confused why Arizona consistently sees the most river water cuts while California, the biggest user of river water and the state with the river's top water rights, didn't see any cuts.

Both state and national water rights, however, may change as the drought worsens.

"The process of the Arizona Reconsultation of the Colorado River is actually already underway," McGuire said.

"The priority system we use now is based on some old, flawed assumptions about hydrology that may have been normal then, but all of those situations have changed. We need to take a look and ask 'does this still make sense?'"

McGuire expects these changes to be long, painful and difficult, especially as the situation worsens. But she looks at examples such as Yuma farmers putting their money where their mouth is, and believes Arizona has set itself up well for success.

Water Wars

Water levels are dwindling across the Southwest as the megadrought continues. Here's how Arizona and local communities are being affected.