ARIZONA, USA — Arizona kicked off 2023 parched.

The state only got around two-thirds of its usual Colorado River water allocation this year. The cut was part of a federal government effort to try and stop Lake Mead and Lake Powell from reaching critically low levels.

Farms throughout the state have the worst water woes; the first to feel the brunt of the water cuts. As the megadrought continues, some cities aren't too far behind.

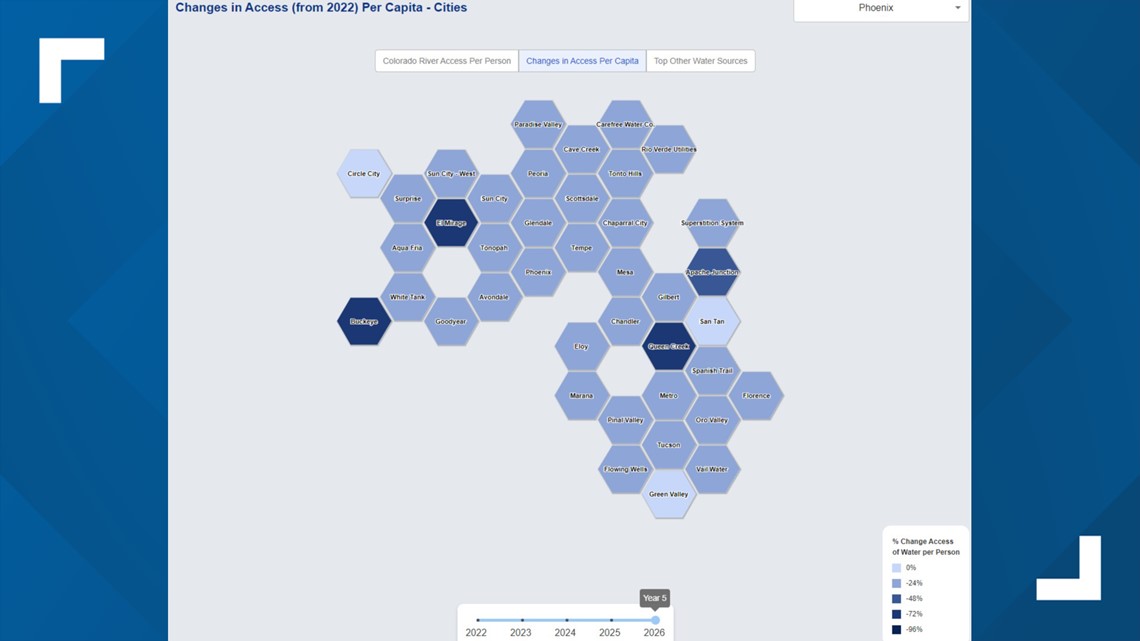

Three Valley cities, specifically, will see the biggest negative changes in water access over the next five years, according to an Arizona State University (ASU) database. The reasons why are cemented in history, while the impact on city water supply can't fully be known until the future plays out.

Which 3 Arizona cities will see the biggest water cuts in the future?

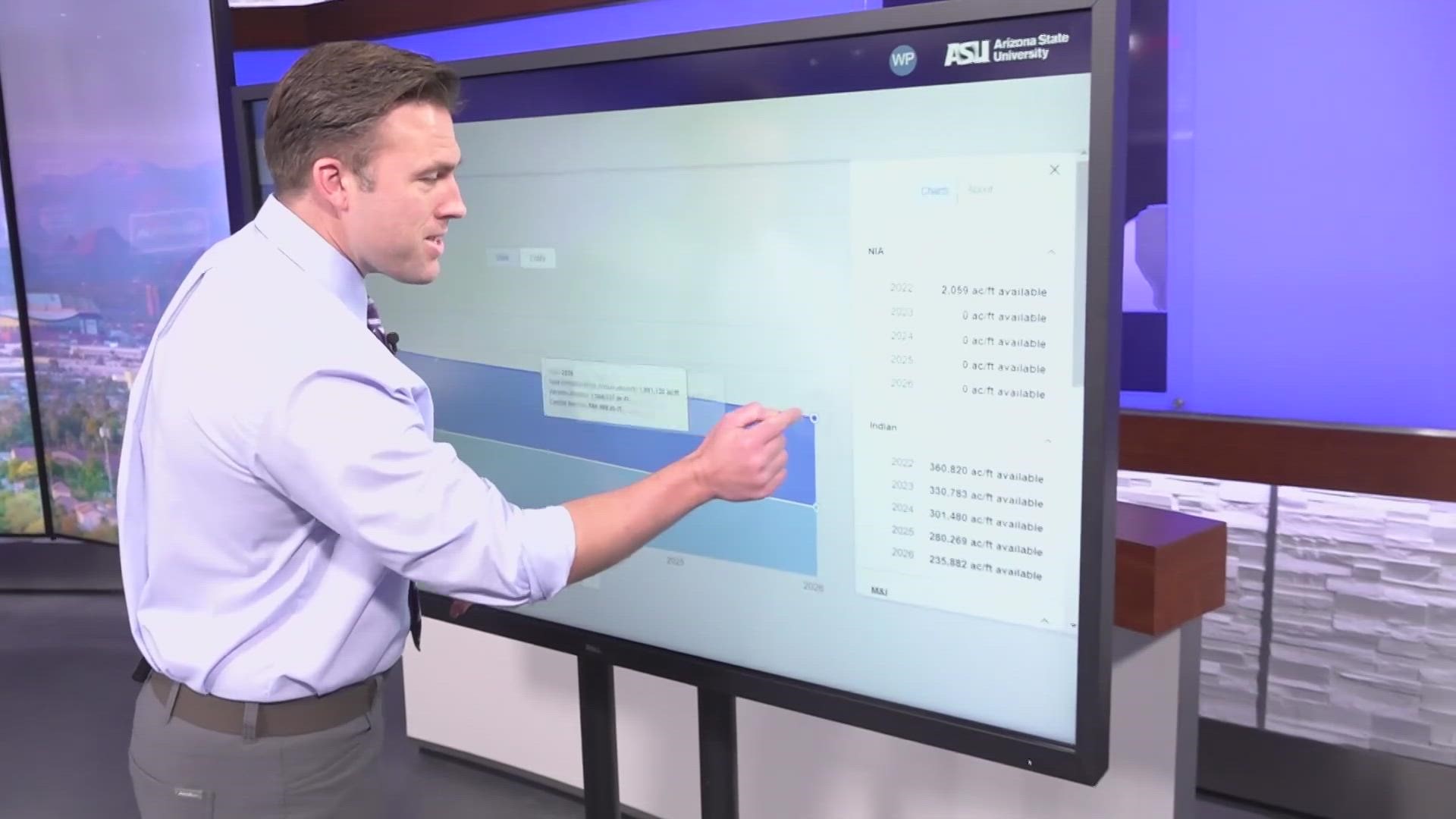

The Arizona Colorado River Visualization Enterprise, or "AZ CuRVE," is the clever name ASU gave the database that allows people to visualize how the Colorado River Shortage will affect the state.

One piece of the dataset is how access will change for people, other water sources and cities.

By 2026, the top three Arizona cities that will see the largest water access reductions per person include:

- Buckeye with a 96% reduction

- Queen Creek with a 93% reduction

- El Mirage with an 82% reduction

How will high water reductions affect Arizona cities?

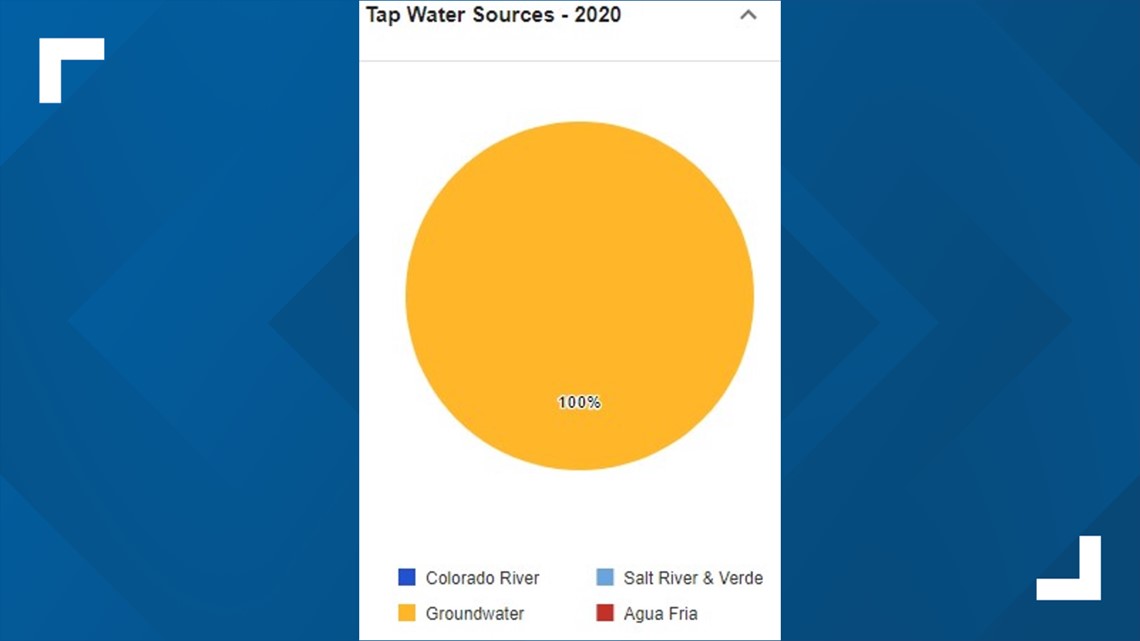

A bit of good news: The water reductions won't affect tap water deliveries for residents in the three cities, at least not immediately.

Buckeye, Queen Creek and El Mirage don't use Colorado River water for tap water deliveries. AZ CuRVE shows that all three cities actually get 100% of their tap water from groundwater as of 2020.

The bad news, however, may jeopardize aquifers each city relies on.

The three cities primarily use Colorado River water to recharge their underground aquifers. In some cases, river water acts as only a small part of that recharge. Queen Creek, for example, will use 495 acre-feet of Colorado River water and 4,000 acre-feet of effluent water, or treated sewage water, to recharge its aquifers.

"[Queen Creek] is primarily using treated effluent to recharge the aquifer – we are working with developers to expand our treated effluent program and in the process of expanding our recharge facilities," the city's communications & marketing manager, Constance Halonen-Wilson, said.

"In addition, by 2026, the Town will have an additional 15,000-acre feet of water supplies to offset groundwater pumping."

The allocation may be small, but any cut could have large consequences for a city's aquifer, according to one of Arizona's top water researchers.

"The story of Colorado River shortage in central Arizona is going to be a story of groundwater depletion," said Kathryn Sorensen, ASU's Morrison Institute for Public Policy's research director and the architect of the AZ CuRVE tool.

The loss of that recharge would exacerbate aquifer collapse, along with residents' drinking water supply. This isn't just true for Buckeye, Queen Creek and El Mirage. It's also true for the vast majority of cities in the Valley.

"Cities will continue to provide that tap water in support of public health and safety, but the consequence of having less Colorado River water is that we won't be able to recharge the aquifers," she said.

Why are Buckeye, Queen Creek and El Mirage at water risk?

Roots are the commonality these three cities share.

Buckeye, Queen Creek and El Mirage are all located on the fringes of the Phoenix metro Valley. Their humble small-town histories make for good tales, but didn't set them up for high-priority water rights.

Both Queen Creek and El Mirage began as little agricultural communities in the early 1900s. Both were filled with residents unaware of the tens of thousands of people who would call the area home more than a century later.

The cities were given a very small, low-priority allocation of Colorado River water in the 1980s because of this humble beginning.

"Irrigation districts in central Arizona have their own allocation of water called "Non-Indian Agricultural water," Sorensen said. "Those irrigation districts ended up not being able to afford that water ... they basically gave up their long-term access to Colorado River water in exchange for subsidized temporary water."

The irrigation districts, in places like Queen Creek and El Mirage, received the benefits of this deal, which Sorensen estimates is around $500 million in benefits. But as Colorado River water levels worsen during the ongoing megadrought, the "temporary water" part of the deal is coming to fruition.

Buckeye is in a similar boat, getting its unofficial start with the construction of the Buckeye Canal in 1885. The canal drew water from the Agua Fria River for agricultural use.

"Twelve thousand inches of water was located and claimed by the locators and a right of way over the public domain forty feet wide to the Hassayampa creek on which to build their canal," the Buckeye Water Conservation and Drainage District's website said.

The original small size of the community and the unique water source set Buckeye up to also get a small, low-priority Colorado River allocation.

All three cities have eclipsed their small starts and are now booming. While Colorado River water may not have played an essential role in each communities' founding, losing their allocations could spell doom for their aquifer's future.

Water Wars

Water levels are dwindling across the Southwest as the megadrought continues. Here's how Arizona and local communities are being affected.