PHOENIX — “[We] used to have a talent night over here on Monday night,” George Irvin Campbell, Jr. – aka “Sweet Irv” - said, sitting at a table outside. “Used to sneak in when we were in high school.”

The three other men and one woman around the table nodded, remembering days that are now only known in black and white photos on the wall of the William Patterson Elks Lodge.

“Back in the heyday, it was really something.”

The Elks Lodge at 7th Avenue and Tonto was once the epicenter of the Black community in Phoenix.

Its talent shows and beauty pageants were legendary.

“Willie Mays is an honorary lifetime member,” Arthur Whitmore said, lounging at the same table.

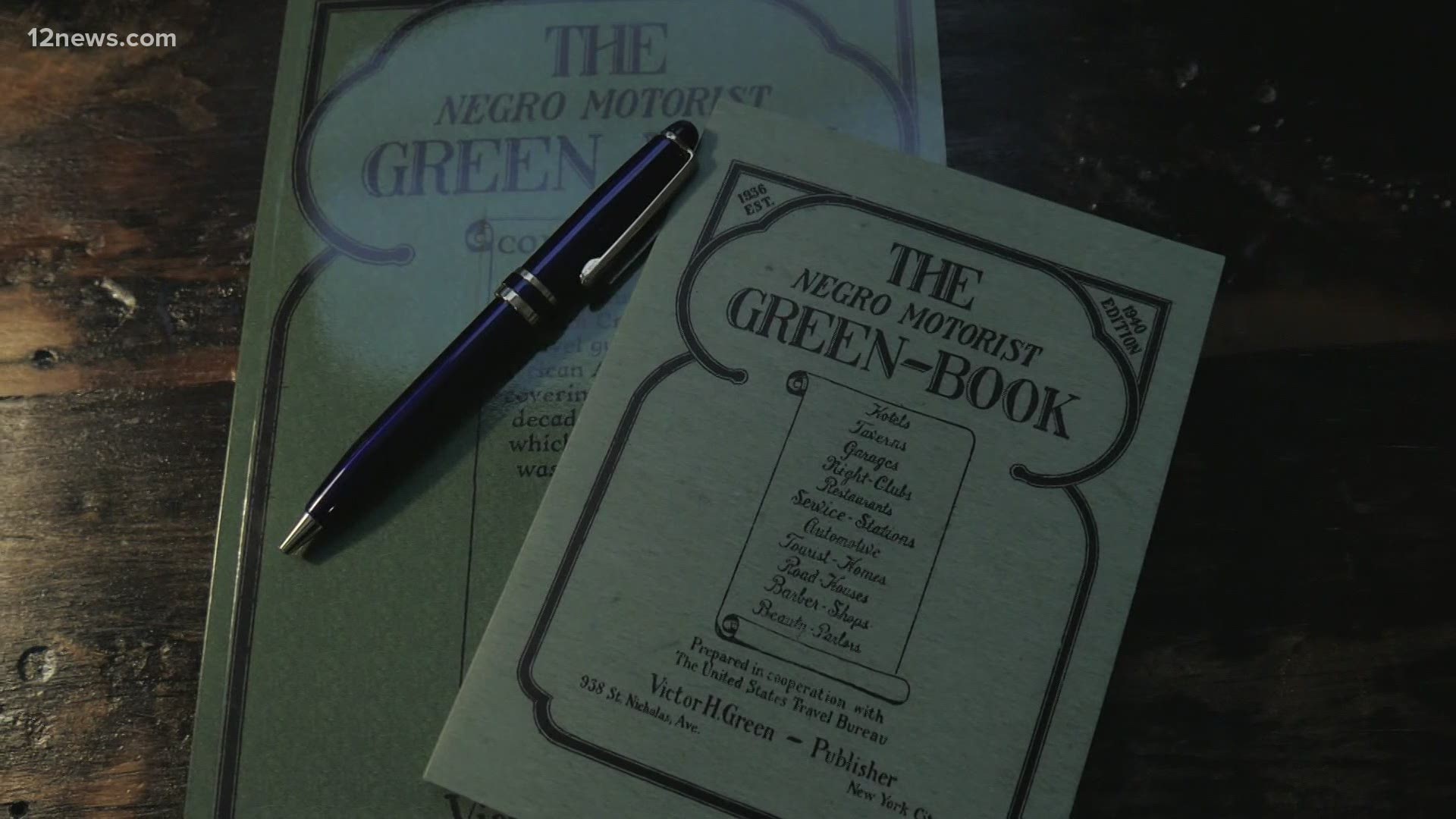

Whitmore, Sweet Irv, and the rest are some of the older members of the Elks Lodge. They remember when it was listed in the Negro Motorist’s Green Book, the unofficial guide to safe places Black people could go while traveling during the 1920s to 1960s.

There were a handful of businesses listed in the Green Book in Arizona. And the Elks Lodge is the only one still in business, almost 100 years later.

“You just went on about your business and left it alone.”

Back in the Elks Lodge’s heyday, racism did exist in Arizona, even though it’s not commonly thought of as a battleground in the civil rights movement. Phoenix was desegregated, if not explicitly so.

“It was settled,” Sweet Irv said. “That didn’t mean it was open like it was in the south. We didn’t have signs but you knew you couldn't go in certain places.”

Sitting around the patio table, they all remembered the time in their lives when they learned racism and segregation existed and when they learned the rest of the world saw them as different.

Maurice Ward is one of the longest-standing members the Elks Lodge has. He remembered going into a diner in downtown Phoenix to get something to eat, and being thrown out on the curb. He was only a boy, and wanted to fight back.”

“I was gonna run at him, but a Black woman caught me by the waist and she said, ‘No, don’t do that, he gonna hurt you,” Ward said.

“When I got home my father had just come back from work and he explained to me about prejudice.”

Lena White went to Phoenix Union High School and wanted to be a cheerleader…until she found out she couldn’t.

“They wouldn't let Blacks be on the cheerleading (team),” White said. “I don’t care what kind of grades you got, you couldn’t be on the cheerleading team.”

And Ernest Austin, wearing a US Navy Veteran’s hat, remembered when he discovered the unwritten rule about movie theaters when he tried to sit close to the screen

“They ushered us all back to the lobby and told us we had to go upstairs because doing the regular movie hours we couldn't sit downstairs,” Austin said.

“And when nobody would do nothing about it, you just went on about your business and left it alone,” White said.

The unwritten, written rules

Which is what made the Green Book so valuable.

All those unwritten rules were written down in plain English, along with a list of safe havens from the Deep South to the Southwest.

Places like Swindall’s Tourist Home, which was a private home that took in boarders.

The Rice Hotel at 7th Street and Jefferson, which was one of the few hotels that explicitly welcome Blacks.

Gardner’s tourist Home at 12th Street and Jefferson.

Those two, plus the Elks Lodge, are the only three left standing after all these years. The rest have been bulldozed, cleared away for condos, parking garages, even Chase Field.

All those safe havens for the Black community lost to time.

“I’m not sad I’m mad!” Sweet Irv said, to a blast of laughter at the table, though Sweet Irv was only partly joking. “They called it urban renewal, right? They split up our whole community, which I don't like.”

The rest of the group sifted through old photo books, looking at memories of days long gone.

But Black History in Arizona isn’t just in the buildings. It’s around the table, in the photos, and on the walls.

More than any pages in a green book.