PHOENIX — Every day, Grand Avenue and Van Buren Street serve as vital lines of transportation throughout the Phoenix area. But back in 1942, they served as a dividing line for an entire community.

On Feb. 19, 1942, Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. The order allowed for the creation of military zones and the removal of people of Japanese descent. The order cut Arizona in half. An arbitrary line was drawn along Grand Avenue and across Van Buren Street.

Folks of Japanese descent on the north side of the line could stay in their homes. Family and friends on the south side of the line were forced to relocate.

“Just that distance determined who would be suspicious and who would not,” Arizona State University professor Karen Leong said.

"That one line represented freedom and unfreedom," Leong added.

Life before the line

Arizona's Japanese community was relatively small. Most were farmers, setting up a community similar to the ones they had back in their own country.

However, alien land laws prevented immigrant farmers from owning the land they worked on. Most immigrants rented out the land and sometimes bought it through their American children once they turned 18.

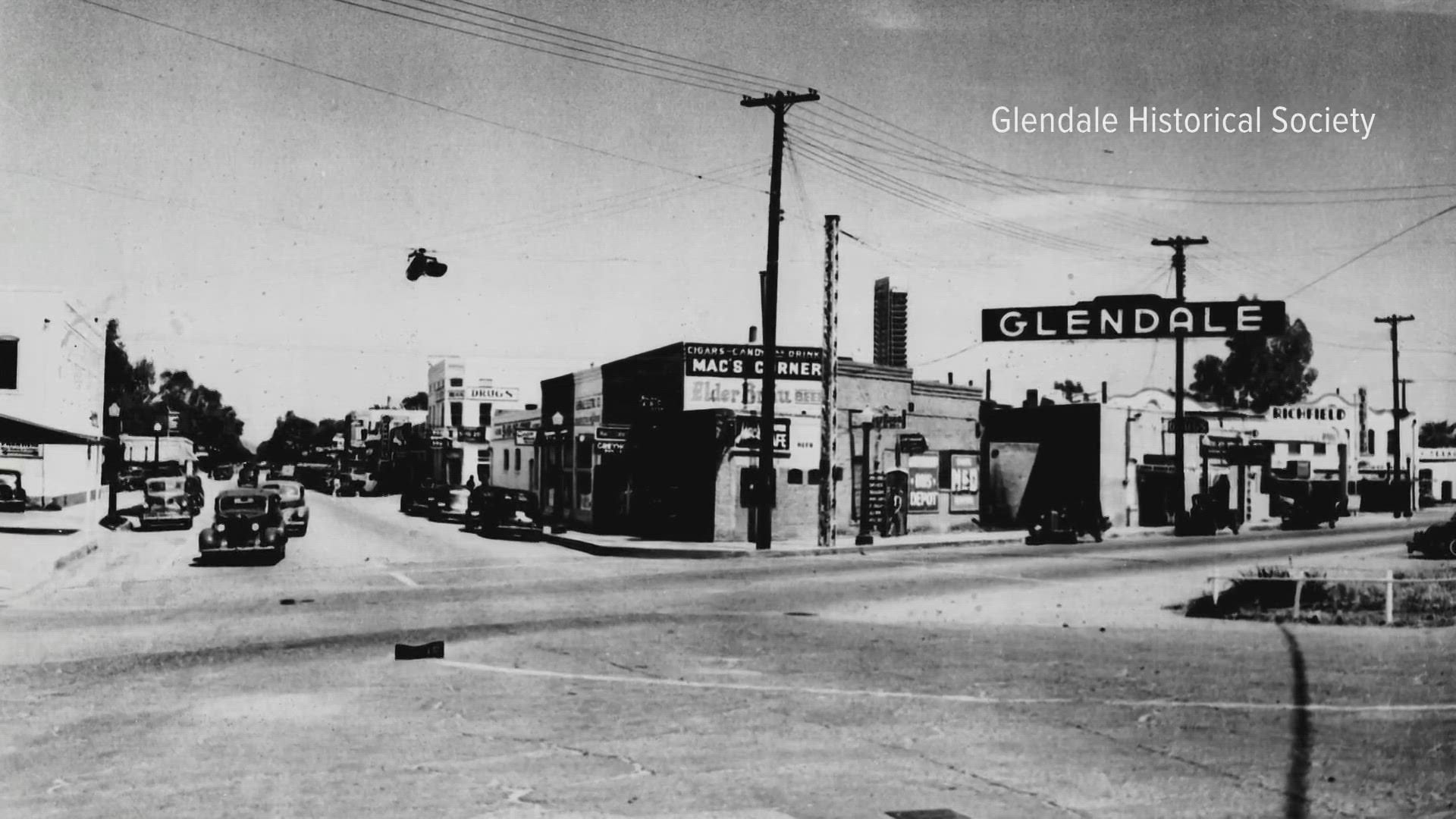

By the 1930s, a small but thriving community was on both sides of Grand Avenue. Japanese Americans built churches, temples, and a Japanese school.

"Even though it was a hard life, they also made due, just like most Americans did," Leong said.

The line

Once order 9066 was enacted, those on the wrong side of the line were forced to relocate or move to military camps.

“They were terrified," Leong said. "It was really traumatic. They had to sell all their belongings really quickly.”

Leong said those leaving homes behind had to trust their homes and belongings to friends.

Life in the barracks was devoid of freedom, as the community tried to make the best of life within a camp.

Arizona had two major camps housing more than 30,000 people, most of them American citizens.

The federal government paid reparations to the families years later and apologized for the illegal incarceration.

Those left behind

Japanese Americans allowed to stay in their homes faced curfews and restrictions.

Professor Leong shared an interview she conducted with Helen Tanita.

Tanita remembered relocating members of the Arizona Japanese community.

"Our parents were like, 'you know you better get married, or you don’t know where you will be going,'" she said.

Tanita's family lived on the north side of the Grand Avenue line. However, her church was on the wrong side.

"We couldn’t get married there," Tanita said.

She eventually found another church that allowed her to get married, but the FBI prevented her brothers or sisters from attending.

“The FBI wouldn’t let us have a big wedding,” Tanita said.

It didn't stop there. When Tanita was pregnant, she said she needed permission from the FBI to go to the hospital. Even then, her husband could not go with her, and she had to be accompanied by a white woman.

“We had to get permission for everything, everything.”

The last internment camp closed in March of 1946.

Up to Speed

Catch up on the latest news and stories on the 12News YouTube channel. Subscribe today.