NAVAJO COUNTY, Ariz. — Mesas don’t just dot the skyline in northeastern Arizona, they dominate it. The area holds sacred and special meanings to its residents. But however beautiful the flat-topped hills may be, they hold a sinister secret as well.

The mesas have sparked a painful battle over contaminated groundwater from abandoned uranium mines that have been sacrificing the people in former mining communities on the Navajo Nation for nearly seven decades.

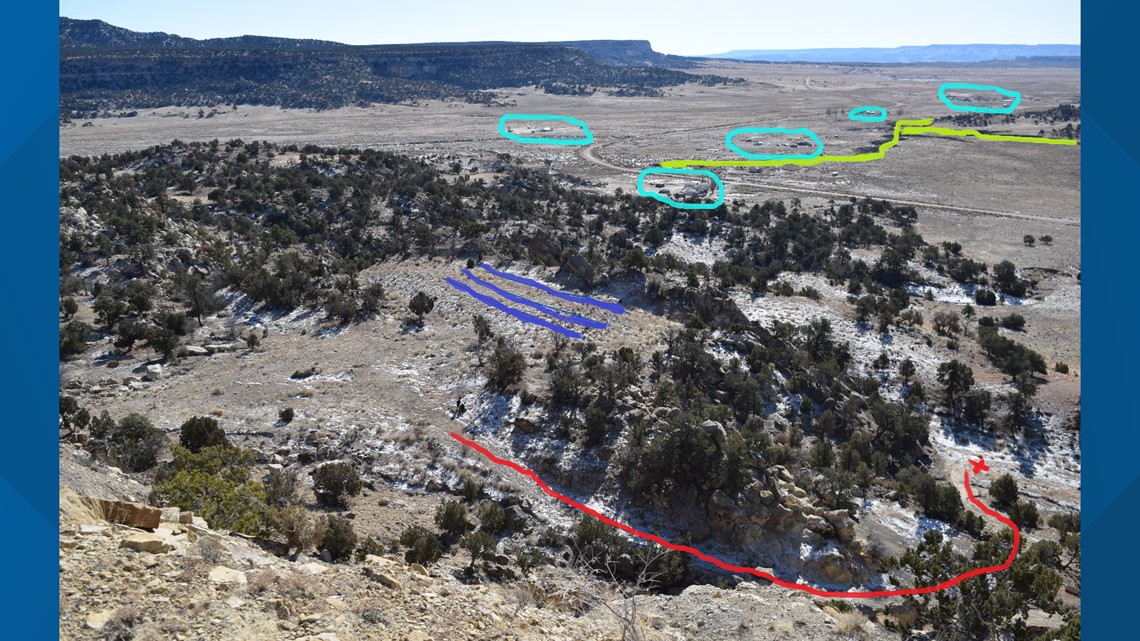

Claim 28, an abandoned uranium mine, is the source of the contamination in Tachee/Blue Gap, Arizona and the federal government’s glacial response in addressing it is the source of the pain and frustration residents feel at the untimely deaths of family members and friends.

“People would still be living if they had done the reclaim before 1992. Cause people walked in it, bathed in it, drank water from that area, and it took all those years to reclaim it,” says Tachee/Blue Gap resident Sadie Bill.

Watch the full documentary below.

Uranium mining on the Navajo Nation dates back to the 1940s. Despite protests from Navajo elders, the United States government moved onto the Nation to mine uranium ore for the Manhattan Project and the creation of atomic bombs.

“Traditionally, culturally, uranium was something we knew we didn’t want to take out of the ground. When WWII happened the United States, to support their Manhattan Project, needed uranium which ultimately developed the first nuclear bomb. We have a lot of uranium ore here, so naturally, they came here,” says Oliver Whaley, the executive director of the Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency.

Officially, there are 524 categorized mine sites that sit on the Navajo Nation, but that calculation may not be entirely accurate.

“A mine site can consist of multiple sites, so you’re probably looking at more like 1,000 at least, that we know of,” says Whaley.

Uranium mining left the Nation for good in the 1980s, but contaminated uranium waste has continued to seep into the communities’ groundwater supply. In the decades since, Tachee/Blue Gap and similar Navajo communities have been facing an uphill battle to get clean groundwater.

Waste from Claim 28 was buried near natural springs within Tachee/Blue Gap, further contaminating the groundwater. According to the senior hydrologist at Navajo Superfund, Elisa Arviso, burying the contamination was meant, “to control the physical hazards of mine sites. But it didn’t fix the problem with water contamination.”

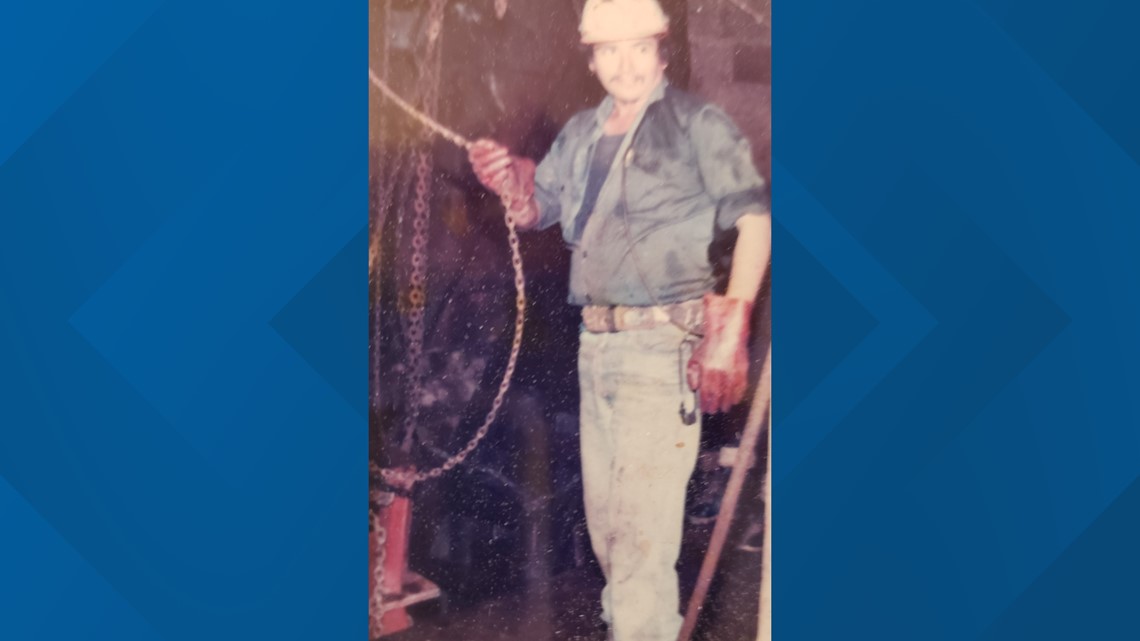

For Elisa, the topic of mining and uranium contamination is deeply personal and especially difficult. Her father, Edison Arviso, worked in the uranium mines and brought home water from the mine to drink and to make the family’s coffee.

“My father worked in uranium mines for many years. I saw the results of that, that ingestion of uranium and being affected by it every day. I know my father would take his thermos and he would go and collect water and bring his jugs of water home. I’d always be the coffee maker, so I’d be using that water. He told me how delicious that water was, and it was.”

Edison was diagnosed with not one but two types of cancer: stomach gastric cancer and prostate cancer. And he’s not alone.

While there is limited data on cancer rates, the Nation’s first cancer center opened in 2019 in Tuba City, the few studies that have been conducted suggest cancer rates for the Navajo far surpass that of Caucasians. Several of those studies have explicitly linked cancer to uranium mining.

A 2000 study from the Southern California Health Sciences Center linked uranium miners and lung cancer. It concluded that 67% of the men studied were former uranium miners and had lung cancer. It states, “Uranium mining contributed substantially to lung cancer among Navajo men over the 25-year period following the end of mining for the Navajo Nation.”

A study from the Navajo Epidemiology Center says that Navajos suffer from high rates of kidney, liver, stomach and gallbladder cancers. It goes on to say that mortality rates among Navajos for cancers of the liver, stomach, kidney and gallbladder are much higher than for Caucasians.

The Navajo Nation works diligently to bring regulated sources of water to the residents of Tachee/Blue Gap, but, access to that water remains one of the biggest challenges.

“We advise people not to use those sources. They are still sources for livestock and a lot of older people, who have historically used them for ceremonial purposes, still use those water sources. It’s a tough issue where water is scarce and precious,” says Whaley.

Additionally, there is no mechanism to control the groundwater from infecting vegetation that could be consumed by livestock or to control pollen that could blow into the air of the community. This means more pathways for contamination are opened up.

“Right now, the community of Tachee/Blue Gap relies on another community that’s near them, which is the Pinion community water system, to supply their water supply needs. So, they’re not able to use their own water source within Blue Gap to provide a source of water,” says Elisa Arviso.

Sending water from Pinion to Tachee/Blue Gap puts a strain on Pinion’s water system. The Navajo Nation, like much of Arizona, is in the midst of a decades-long drought. Sending water away from the residents of Pinion to supply another community’s water needs only adds to the water problems facing the Nation and is a short-term solution that solves none of them.

Long-term solutions to clean groundwater are more difficult to come by. Often what the Navajo Nation wants is not what the federal government or private parties responsible for clean-up want. Solutions come down to what the cheapest thing to do is.

Clean-up “is expensive and it’s bad PR, so I think it’s probably controlling the cost as well as the public outcry. With 219 [of the] sites it’s going to be about $1.7 billion available to address those sites. We don’t yet know if that’s even going to be enough. For the other 305 it’s going to be three, probably more like $4 billion, to address it,” says Whaley.

Whaley says there is an overwhelming sense that the Navajo people have been sacrificed through uranium mining without proper compensation.

“I think we’ve given a lot in terms of contributing to the freedoms that people have here, and we haven’t really asked anything for it and, in this instance, addressing it and providing funding is the right thing to do.”

Not content to wait for the federal government to act, the Navajo Nation passed a resolution to solidify their position on the uranium clean-up in December 2019. The position reads, in part, “Uranium mining on the Navajo Nation has devastated both our lands and our way of life as Diné people. The impact has not only been physical but also spiritual and emotional as well. This is why the issue of uranium contamination on the Navajo Nation is such an important and time-sensitive issue for our Navajo people. How can we live in harmony and balance when our people are chronically being exposed to radiation and our Mother Earth has been exploited and scarred with abandoned uranium mines?”

Whaley sees the resolution as a tool to move forward with the U.S. EPA and to potentially garner support from members of Congress for comprehensive legislation that would allocate funds for the remaining 305 sites waiting to be addressed.

“It’s a time-sensitive issue and it’s gone on too long and we need to start moving forward,” Whaley said.

And while they wait for the clean-up to be addressed and the proper funding to come through, waste from the mines across Navajo continues to seep into the groundwater supply, people continue to get sick with higher than normal rates of cancer, heart disease, lung disease and kidney disease and people continue to die from these illnesses related to uranium contamination.

“For me, it’s a matter of time. Will I see the effects of ingesting that water? Probably. I saw my father go through it and I see my close relatives go through it and experience cancer because of the uranium contamination and what we were exposed to,” says Elisa.

Tragically, Elisa’s father eventually succumbed to his illness. Edison passed away on April 22, 2019, from stomach gastric cancer. He was 69 years old.