PHOENIX — The family of Deana Bowdoin has waited 44 years for justice.

Next week, the man who brutally murdered the 21-year-old Arizona State University honors student in 1978 is scheduled to be executed at the state prison in Florence.

It's the first execution in Arizona in eight years, and it casts a spotlight on what one critic has called the state's "relentless search" for ways to put condemned inmates to death.

Arizona is moving ahead with executions again, even as most states are backing off.

Over more than a decade, Arizona's search for new execution methods has skirted the law, seen the state refurbish a gas chamber, and operated largely behind a veil of secrecy.

A botched execution in 2014 proved to be a turning point that tested the state's commitment to enforcing the death penalty.

'Gasping and gulping'

One dose of a lethal injection was supposed to kill Joseph Wood in 10 minutes.

"It was a clear gasp. It sort of looked like a fish opening and closing his mouth," said Michael Kiefer, a journalist at the Arizona Republic who was an execution witness.

According to Kiefer and other witnesses, the double-murder convict writhed for almost two hours before he died. He had been injected with 15 doses of a two-drug cocktail.

"He was gasping and gulping," said Dale Baich, a federal public defender who represented Wood. Baich worked on death penalty cases for 25 years.

"We were actually arguing in front of a federal judge to stop the execution as it was going forward."

The appeal failed.

'To hell with you guys'

"Prior to the execution, the state said, one dose will do it," Baich said in an interview. "They were wrong."

Wood had murdered his ex-girlfriend and her father. Their relatives saw the execution very differently.

"He smiled and laughed at us and then went to sleep," Richard Brown, a member of the victims' family, told reporters.

"All you people that think these drugs are bad. Well, to hell with you guys."

A scramble for suppliers

For several years leading up to the Wood fiasco, Arizona had scrambled to buy execution drugs, often in Europe.

"Lethal injection was first introduced in this country in 1977," said Deborah Denno, a Fordham University professor who is an expert on execution methods.

"From that time, up to about 2009, most states used the same three-drug formula. Starting in 2009, that first drug no longer became available."

Drugs at a driving school

Arizona's search for drugs had embarrassing results.

A year after the execution of Jeffrey Landrigan in 2010. documents in the United Kingdom revealed that Arizona prison officials obtained the lethal injection drugs from a tiny pharmaceutical company, housed in the back of a London driving school.

But that didn't deter state prison officials.

"After a federal judge in 2012 issued an order prohibiting the importation of the drugs in 2015, Arizona tried the same thing," Baich said.

"But this time the drugs were stopped at the border. What we have learned over the years is that the states should be transparent."

No answers on Wood's execution

The Wood execution resulted in a moratorium on capital punishment, as well as lawsuits against the state.

But it was hard to get answers about what happened to Wood.

"What we don't know is why 14 additional doses were administered," Baich said. "We don't know where the state got the drugs, we don't know who was making the decision to proceed after a backup dose of drugs didn't work."

The state never had to disclose the information after it abruptly announced the drugs wouldn't be used again, Baich said.

'Ever study the Holocaust?'

With the difficulty of getting execution drugs, an old execution method became new again. Arizona refurbished a gas chamber last used decades ago.

"Did anybody that was associated with this process ever study the holocaust?" said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center.

Condemned inmates can now be put to death with a lethal injection or with chemicals similar to the gas that killed millions in Nazi death camps. The inmate gets to choose.

"The gas chamber is the least effective method of execution. It's the most torturous," Denno said.

"I would go so far as to say every gas execution is per se torturous."

Executions plunge to a 20-year low

Arizona's first execution in eight years comes as prosecutors nationwide are backing away from the death penalty.

Just 18 death sentences were imposed in 2021, down 94 percent from the late 1990s peak, according to the Death Penalty Information Center

There were only 11 executions last year, down 89% from the peak.

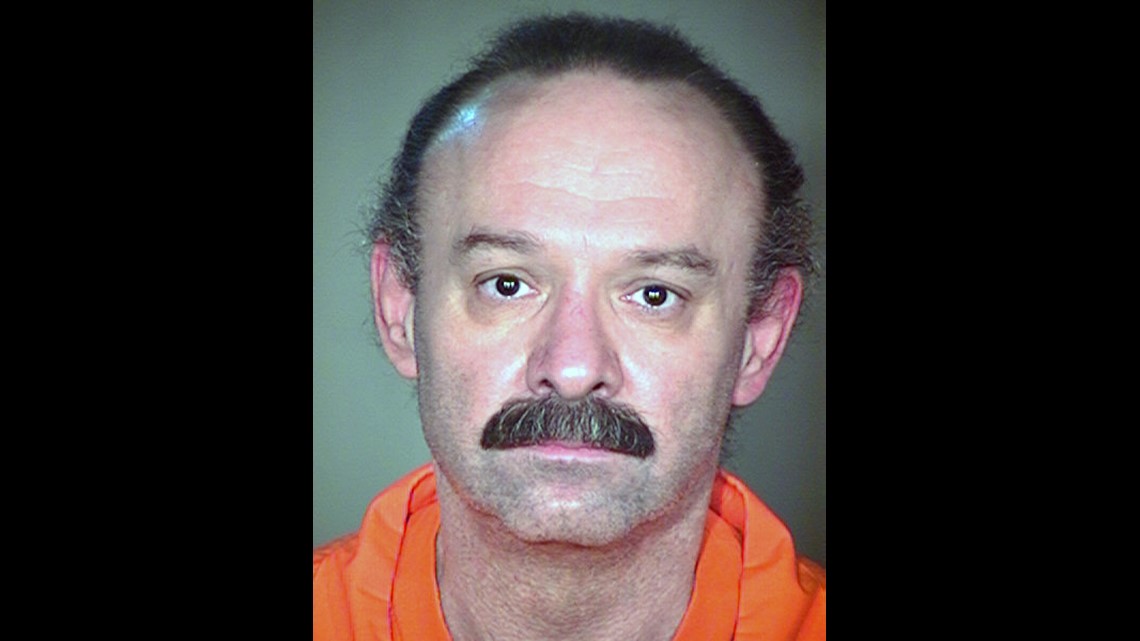

Clarence Dixon, a 66-year-old Navajo man, is set to be executed with a single dose of the sedative pentobarbital.

The U.S. Justice Department quietly developed a network of pentobarbital suppliers before resuming federal executions two years ago, according to a Reuters investigation.

Arizona found its own supplier. An investigation by The Guardian revealed the state paid $1.5 million two years ago for 1,000 vials of pentobarbital sodium salt, shipped in "unmarked jars and boxes."

'The appropriate response'

Shortly after that disclosure, Republican Attorney General Mark Brnovich announced he was putting executions on a fast track.

Brnovich, who is running for the U.S. Senate, tweeted at the time: Capital punishment... is the appropriate response to those who commit the most shocking and vile murders."

A second execution is scheduled for next month

A repeat of Wood's execution?

Deborah Denno warns the Dixon execution could unfold much like Joseph Wood's eight years ago.

"The first lethal injection execution occurred in 1982, and that injection was botched," she said. "That's always been a problematic method of execution. But it's only gotten worse over the past decade, because of this scramble and experimentation with drugs."

"There's every reason to expect that the execution of Clarence Dixon, for example, is going to be very similar to the botched execution of Joseph Wood."

Dixon's attorneys have argued that he's schizophrenic and doesn't understand why he faces execution. So far, legal efforts have failed to block the scheduled execution.

Dixon was connected to Deana Bowdoin's murder almost 30 years after her death. A cold case detective with Tempe police used DNA evidence to track down Dixon.

'Traumatic for families'

In 2008, Dixon was sentenced to death for raping and killing Bowdoin in her Tempe apartment.

"It can be very challenging, very traumatic for families," Colleen Clase, a victims' rights attorney at Arizona Voice for Crime Victims.

"It can be traumatic to be in a courtroom where the offender is being made out to be the victim when they are the victims."

Clase's organization has helped people like Deana Bowdoin's surviving sister, Leslie Bowdoin James, seek justice by asserting their rights as crime victims.

Deana's sister at 42 hearings

"I would bet that I'm the only one in this room that attended every one of 42 hearings, every day of trial, and I followed and watched this inmate during every moment of those proceedings," James said at a recent commutation hearing for Dixon.

"Leslie has always been very active," Clase said.

James has issued this statement: "I will never stop thinking of Deana, but I look forward to the resolution of Dixon's criminal matter through the imposition of punishment."

I asked Clase how crime victims move on after an execution.

"Closure is not the right word," she said. "But there will be a close to the criminal proceedings. The emotional damage is always going to be there for any victim of any crime... the victimization itself is always going to be there."

Up to Speed

Catch up on the latest news and stories on the 12 News YouTube channel. Subscribe today.