ARIZONA, USA — Editor's Note: The above video is from previous coverage of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day in Arizona.

Black history is American history.

And State 48 has a rich Black history made up of trailblazers and changemakers who left a lasting impact on not just Arizona but the entire country.

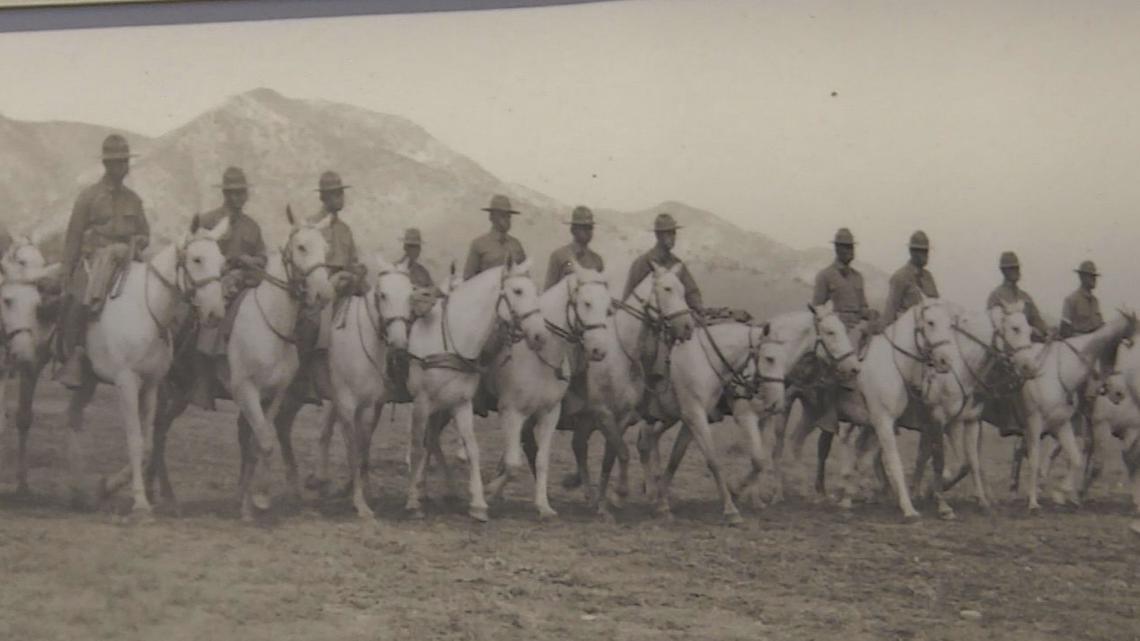

Buffalo Soldiers forged the path forward for Black Arizonans (1866)

Black Americans began making history in Arizona before it even became an official state.

In the summer of 1866, the first regular Army regiments made up of all African American soldiers were formed. They would later be known as Buffalo Soldiers.

In Arizona, they helped developed small settlements that would grow into towns and cities. Towns and cities, they would not be welcomed in.

Buffalo Soldiers not only helped develop the west and the Grand Canyon state we call home, but they laid a foundation for African Americans and other minorities to work toward their own American dream.

Tanner Chapel A.M.E Church holds strong (1929)

Church is a staple in the African American community. It is a place to find fellowship, support, resources and healing.

Tanner Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church is the oldest African American church in the state.

The church was built in 1929, but the congregation organized as early as 1886. The church, located on 8th Street in Phoenix, still serves its congregation. Services are held every week.

The historic Tanner Chapel A.M.E. is famed as the only Arizona church Martin Luther King visited. King delivered a sermon at the church in 1964, according to the Arizona Capitol Museum.

Arizona students of color struggle for education and opportunity (1912-1953)

While the fight for education equity for all students continues, the period between 1909 and 1953 in Arizona was especially difficult for students of color.

According to Arizona State University archives, the state maintained various levels of segregation in schools throughout that time.

Tucson’s Dunbar School opened in 1912. It was Tucson’s first and only segregated school for African American students. It closed when segregation ended and was turned into a cultural center.

In 1925, the Dunbar School opened in Phoenix for African American students.

The Phoenix Union Colored High School, which later was named George Washington Carver High School opened in 1926. It is now the George Washington Carver Museum and Cultural Center.

Civil rights leaders and educators were at the forefront of the fight to integrate schools and establish equal opportunities for students of color in Phoenix and throughout the state.

A pair of changemakers (1940s)

Lincoln and Eleanor Ragsdale were prominent civil rights leaders and educators in Arizona during the 1940s and beyond. They founded the Greater Phoenix Council for Civic Unity.

The Ragsdales pushed for equality on many fronts and they made a major contribution to the fight to integrate schools.

In 1952, the Ragsdales along with the NAACP and GPCCU sued the Phoenix Union High School District challenging segregation.

A judge in the case ruled segregation was illegal in 1953, the year before the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, which the U.S. Supreme Court found school segregation to be unconstitutional.

New heights for Black educators (1933)

Elgie Mike Batteau was the first Black woman to graduate with a master’s degree in teaching. She was also one of the first Black women to graduate from University of Arizona in 1933, paving the way for other Black educators.

Batteau is described as a dedicated educator and civil rights leader, who taught at all-Black schools in Tucson and Phoenix, according to the Tucson Unified School District.

She at one point taught special education at what is now Pueblo Magnet High School.

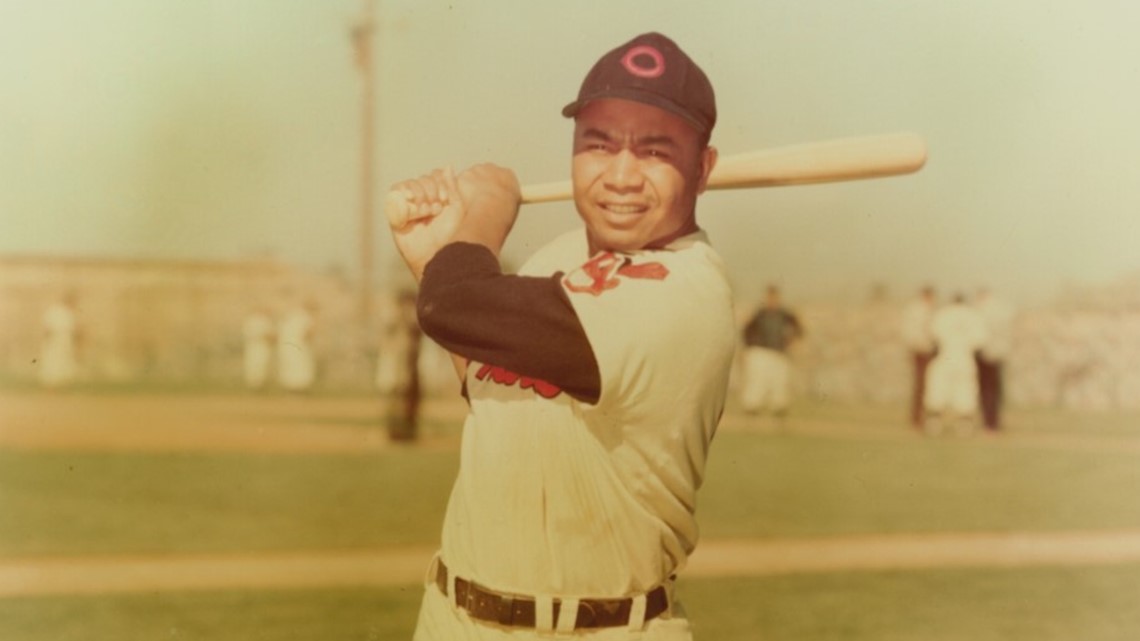

Striking out segregation (1940s)

Nearly 20 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law, banning segregation in schools, restaurants and hotels, integration was happening in baseball.

Jackie Robinson shattered the color barrier in baseball when he started for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, becoming the first African American player to play in the Major Leagues. Robinson was followed shortly after by Larry Doby.

Doby joined the Indians in Tucson as Arizona’s spring training kicked off.

In communities like Phoenix, Mesa, Scottsdale and Tucson Black players were still not welcome in many bars and restaurants. Players had to stay in people’s homes because hotels turned them away.

Future Cactus League Hall of Fame inductees Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, Willie Mays, and Ernie Banks would face the harsh realities of segregation as they forged a path for other minorities to play in the big leagues.

The journey to an equal playing field for minorities in the United States is reflected in its favorite pastime.

Beyond the baseline of racial barriers (1972-82)

Frederick “The Fox” Snowden became the first African American head coach at a major university and the second Black head coach at a D1 school in America.

He was the head coach of the University of Arizona men’s basketball team from 1972 to 1982, according to the University of Arizona Hall of Fame.

He was inducted into the University of Arizona Hall of Fame in 1988.

From the classroom to City Hall (1960s)

Dr. Morrison Warren became Phoenix’s first Black city council member in 1965. He later became the city’s vice mayor.

After serving in the military during WWII, Warren began studying at Arizona State University (it was known as Arizona State College at the time), according to the Historical League based in Tempe.

A graduate of Phoenix Union Colored High School, Warren dedicated his life to education and uplifting the Black community.

He took many paths to accomplish that including heading various community organizations and taking on roles in city leadership.

A Black voice in state politics and society (1960s)

Dr. Cloves Campbell Sr. served in the Arizona state legislature for 10 years, as a State House representative and the first Black person elected to the State Senate, according to Arizona State University.

Campbell pushed for legislation aimed to support the diverse communities in the state.

He was a major force behind legislative moves to make Martin Luther King, Jr. Day a formal holiday in Arizona.

Campbell and his brother Dr. Charles Campbell launched the Arizona Informant newspaper--designed to report Black stories and history-- in 1971. It is one of the longest running and most widely circulated weekly papers in the state.

The long march to Martin Luther King, Jr. Day in Arizona (1992)

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day became a state holiday in 1992, years after it became a national holiday, according to the Pima County Library.

Civil rights leaders and community organizations fought to get the holiday recognized throughout the state.

Two separate propositions to institute the holiday failed.

The holiday was finally approved after the City of Phoenix lost the 1993 Super Bowl due to backlash over the rejection of MLK Day. Phoenix lost a projected $200 million in revenue.

Arizona voters approved the Martin Luther King Civil Rights Day holiday in November 1992.

The Grand Canyon State was the last state to formally instate the MLK holiday. However, it was the only state to approve the holiday by popular vote.

Since then, the holiday has been marked by Arizonans across the state with marches, community service projects, celebrations and discussions to further King’s legacy and goal of equality for everyone.