PHOENIX —

Editor's note: Part 3 of this series airs on 12 News at 10.

Experts say every time a seriously mentally ill person is discharged with no place to go, it’s like throwing a lit match into the street.

Sometimes, it burns out. But sometimes, it bursts into flames.

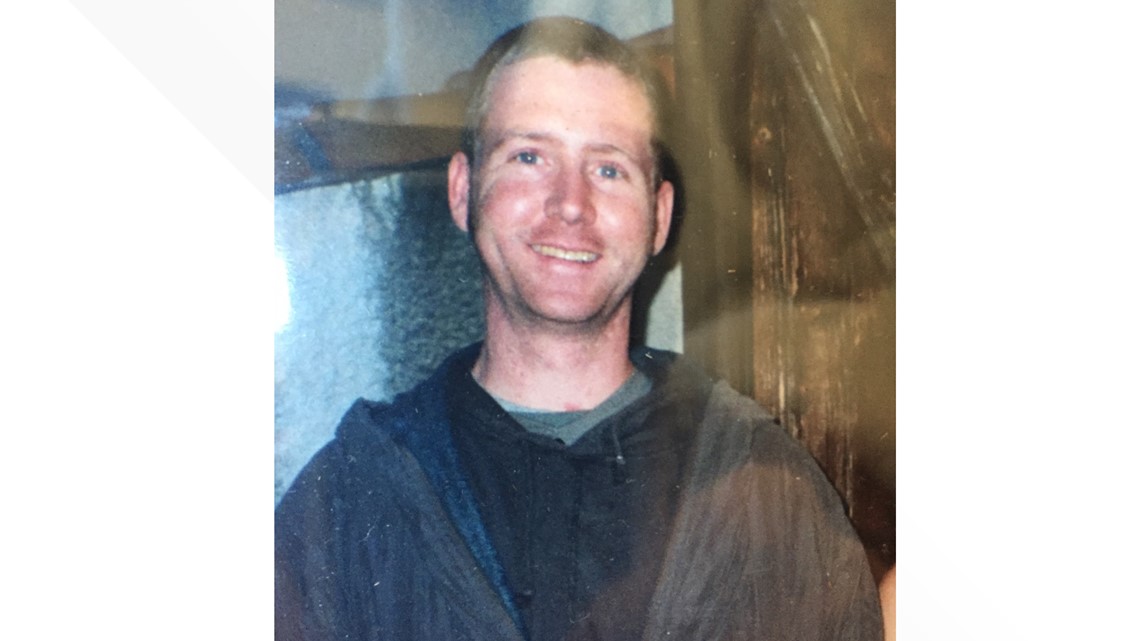

“The saying is treat, street, repeat,” said Sommer Walter. “And that’s exactly what happened with my brother. My brother Darren is the individual that burned down the one-n-ten youth community center in downtown Phoenix.”

In July of 2017, Sommer’s brother, Darren Beach, walked into one-n-ten in Phoenix, an LGBTQ youth center. Surveillance video shows Beach dousing the floor with gasoline then setting the building on fire.

Sommer had lost touch with her brother for several years. She was shocked when she saw news of the fire and that her brother was responsible.

She visited him in custody and asked him why he did it.

“He believed that the building itself was killing his grandmother. And his grandmother has been deceased for many, many, many years,” said Sommer.

“I knew something was wrong. I knew my brother was sick.”

As charges were filed against Beach, Sommer started digging. She became his power of attorney and started combing through her brother’s medical history. What she found leads her to believe the devastating fire could have, and should have been prevented.

Beach was diagnosed bipolar and had been designated by the state as seriously mentally ill. That means he should have been getting consistent care and treatment.

“They get discharged back to the streets. And the vicious cycle just continues,” Sommer said.

More than a year before the arson, medical records show Beach went into a behavioral health center begging for long-term treatment. Documents show Beach pleaded with staff to keep him there so he didn’t have to go back to Central Arizona Shelter Services, or CASS. It’s the homeless shelter in Phoenix.

Despite Beach’s pleas, after just a couple of days at the behavioral health facility, he was discharged directly to the homeless shelter.

Southwest Behavioral Health Services did not return multiple requests for comment for this story.

“They couldn’t even give him a ride to the shelter. They had him transport himself,” Sommer said.

“To have someone with known mental illness being released to a homeless shelter is a serious resource problem,” said Lisa Glow, the CEO of CASS.

According to AHCCCS, there are more than 41,000 Arizonans designated seriously mentally ill as of 2019.

Lisa Glow, the CEO of CASS, said at least 40 percent of people coming into CASS are dealing with a serious mental illness. She believes that number is much higher because members are self-reporting.

“We don’t have enough appropriate treatment centers for someone to be released to,” Glow said.

Sommer said there are no long-term treatment options for people like her brother.

“One of the things when my brother was arrested was ‘Oh he’s a monster.’ He’s not. He’s not at all. He’s just sick. He’s sick and he needs help.” Sommer said. “They didn’t choose this. Nobody would choose this.”

Darren Beach’s story is not unique

The 12 News I-Team has analyzed violent crimes that made headlines over the past two years and discovered in many cases, they involved someone with a documented history of mental illness who was not getting continuous care or treatment.

The Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System Administration, the state’s Medicaid system, oversees the treatment of those designated seriously mentally ill. 12 News made multiple and repeated attempts to interview AHCCCS director Jami Snyder.

Through a spokesperson, Snyder declined those requests.

Michael Paul Adams

In July of 2019, Michael Paul Adams was charged in the slaying of 17-year-old Elijah Al-Amin. Police said the attack happened because the teen was listening to rap music and that irritated Adams.

PREVIOUSLY: Before he allegedly stabbed a teen to death, suspect blamed a verbal attack on rap music, prison records show

PREVIOUSLY: Man accused of stabbing 17-year-old at Peoria Circle K has a lengthy criminal history

Although Department of Corrections officials said Adams was not designated seriously mentally ill, Adams does have a court documented history of mental illness. He was released from custody just two days before the murder.

The Department of Corrections declined 12 News’ request for an interview to discuss the treatment and release of seriously mentally ill inmates from prison.

Instead, a spokesperson stated in an email, “This isn’t something that a representative from ADC would be available to speak to.”

Matthew Rasmussen

In November of 2019, Matthew Rasmussen was shot and killed by Glendale Police outside of a Taco Bell.

PREVIOUSLY: Glendale Police release body camera video in deadly officer-involved shooting outside Taco Bell

Just months before the deadly shooting, a judge had deemed Rasmussen not competent, saying without immediate or continued hospitalization, he could hurt himself or others.

Rasmussen was ordered to Desert Vista Behavioral Health Center, now called Valleywise. He was shortly back out on the streets.

Desiree Ortiz

In January of this year, Desiree Ortiz was accused of trying to steal a baby right out of a stranger’s arms.

Her family points to Arizona’s 72-hour mental health evaluation window as a failure. It forces agencies to either file a petition for court ordered treatment or release the person in most cases.

"They should keep them longer than the 72 hours revolving door. They get her medicated and they kick her out the door," said Nick Rider, Ortiz’s brother.

Curtis Bagley

One of the most infamous and egregious cases in recent history is that of Curtis Bagley. Bagley was released from prison on March 17, 2018.

According to a civil lawsuit, following his release, a team from Southwest Network was supposed to provide services to him but they failed to keep track of Bagley’s whereabouts.

Bagley then checked himself into another behavioral healthcare provider, Community Bridges, asking for help. He was discharged to the streets. After an incident outside of 12 News in downtown Phoenix later that same month, he was admitted to another facility. He was again discharged to the streets.

On March 31, 2018 he’s accused of breaking into a home at random and murdering Joshua Fitzpatrick in the middle of the night.

Families say they have no options

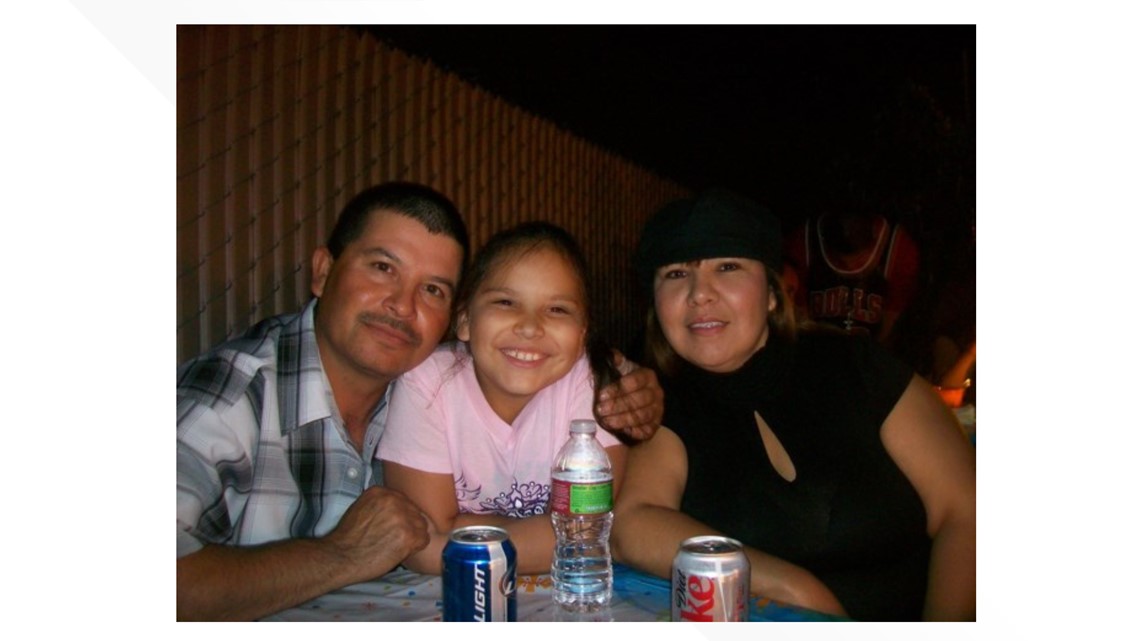

Sonia Ramirez has experienced the worst loss a parent can imagine.

“My house went from a loud, all the TVs on in the room full of love to down to me and my husband, quiet. And that’s kind of sad. And it’s sad because it just happened overnight,” Sonia said.

At 15 years old, her daughter Reyna was murdered. The killer was Sonia’s own son.

“To this day he doesn’t think there’s anything wrong with him,” Sonia said about her son.

12 News is not naming Sonia’s son as she stated she feared he would be targeted in jail if his mental health status was known.

Shortly after her son turned 18, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. The doctor also said he had suicidal thoughts and depression. After that diagnosis, Sonia assumed her son would stay in the facility for treatment.

She was wrong.

“You’re telling me that this person has schizophrenia and he’s depressed and he might commit suicide but you’re giving him the choice to leave or stay. Well of course my son said ‘I’m gonna leave, I don’t want to stay.’ And he left,” Sonia said.

Reyna’s murder happened just a few months later.

“Five o’clock I got out of work and went home and I heard like yelling or something and I ran in the house. So I ran in there and I see my husband and my son on the floor,” Sonia said.

In 911 calls, you can hear Sonia telling the dispatcher she doesn’t know where her daughter is. Police showed up and restrained her son. Then, her attention turned to Reyna.

“I’m like where is she? And he says ‘I let her go,’” Sonia said through tears. “I don’t remember what I felt. I couldn’t see anything. I didn’t see her, thank the lord I didn’t see her.”

“This all happened because of mental health illness and something has to change,” Sonia said.

There aren’t enough beds

Despite the state having more than 41,000 individuals who are designated seriously mentally ill, Maricopa County only has 55 long-term beds available for families to send their loved ones.

The Arizona State Hospital is home to all 55. Experts say it is easier to get into Harvard.

“That’s about 1 bed per 100,000 people. What experts say we need is 30-40 per 100,000,” said attorney Josh Mozell.

Arizona ranked 48th in the nation in having enough beds for those designated seriously mentally ill, according to Treatment Advocacy Center.

“For all intents and purposes, the one place where you might be able to get a long-term stay is not available to the public,” Mozell said.

The shortage of long-term beds then forces facilities designated for short-term stabilization to house individuals for much longer than they believe is appropriate.

“The various hospital systems have been trying to find both short term and long-term solutions to fix this problem,” said Gene Cavallo, the senior vice president of behavioral health services at Valleywise.

Valleywise is the only provider of inpatient, court-ordered evaluation in Maricopa County. It’s growing with nearly 400 beds available. But those beds are not meant for long-term stays.

As 12 News toured the new Valleywise facility in Maryvale, Cavallo pointed out that the environment is set up more like a hospital as opposed to a residential facility. Patients don’t have a lot of privacy and often share rooms.

While it is not meant for long-term residents, they frequently see the same patients returning.

“Stabilizing someone in the hospital is the first step but if they don’t get continued effective treatment beyond that things are just going to return,” Cavallo said. “And they’ll have to come back in and unfortunately we do have a number of people every year who come back in once twice more than twice and I look at that as a failure of the system in general.”

Arizona looks to national leaders for help

For State Representative Nancy Barto (R-15), the problem of Arizona’s broken behavioral health system hits close to home. Years ago, her brother, who was homeless and seriously mentally ill, was murdered in Tucson.

She has made improving mental health services a personal priority.

Two months ago, she and other Arizona lawmakers were invited to the White House to hear from President Trump about improving mental health across the country. In particular, treatment for the homeless.

“Of the 11 million Americans living with severe mental illness, four million receive no mental health service of any kind. Four million people,” the president said. “We have to take care of our mentally ill. We have to help people that are having problems.”

“We have inhumanely treated those with mental illness. We have jailed them, imprisoned them rather than giving them treatment,” Barto said.

What’s working in the current system?

For more than 20 years, Dick Dunseath tried to find the best care for his son Mike.

“He’s a gentle, kind person. Wouldn’t hurt a fly,” said Dick Dunseath. “But he sometimes believes he killed somebody in Mexico even though he’s never been to Mexico but he did this telepathically.”

Mike is one of the more than 41,000 individuals in Arizona who is designated seriously mentally ill. He is schizophrenic and finding treatment that works for him has been nearly impossible for the Dunseath family.

“My son has been in several residential treatment programs because he is more severe than the average,” Dunseath said.

Arizona has a number of residential treatment programs that are accessible to those who voluntarily seek help, as opposed to being involuntarily committed. However, Dunseath said one of the problems his family faced is that residential programs for the seriously mentally ill have strict rules.

If you don’t follow them, you’re at risk of losing your bed.

Dunseath said his son has been kicked out of too many treatment centers to count.

“There’s a huge gap in our continuum of care. That people with this severity of illness they fall into that gap. Meaning there’s no place to go,” Dunseath said.

That’s why Copa Health MARC Community Resources created what they call “lighthouses.”

Lighthouses are homes for the seriously mentally ill where evictions don’t happen.

It’s where Dunseath’s son has been for the past three years and so far, he says it’s working.

“We are very proud of this concept,” said Dr. Shar Najafi-Piper, Copa Health’s CEO.

They have around a dozen homes across the Valley, each with four to five beds. All of them are full.

“Folks are not only attaining their outcomes. They’re also working. They’re also not being incarcerated or being hospitalized; so those outcomes speak volumes,” Najafi-Piper said.

While they work to expand their lighthouse program, the state is working to address another gap in the system.

In 2019, a bill passed allowing for a secured residential facility pilot program. It allocated $3.5 million to build a secured facility for the most severe cases. Individuals would live in a home but it would have a secured perimeter.

The state is now in the process of figuring out who is going to build it.

“There are more people who are dealing with this than you might think,” Dunseath said.

While Dunseath believes there is still work to be done, he is hopeful the state is heading in the right direction.

“We have a pretty good system for most of this population. Around I would guess 90 percent. But somewhere around ten percent, it’s a completely different world,” Dunseath said.

“The system does not work for these people.”