Springerville and Eagar are two towns put together have a population of about 5,000. And right in the middle of town stands the Round Valley Dome. It’s the only domed football stadium in the country. And if you put everyone in town together inside the dome you would probably have seats left over.

Football is a big deal

And If you were a senior football player you not only ruled the school but you also ruled the town. Chris Wilson was one of those players.

I’ve known Chris for years. We went to high school together. We weren’t close, but with a senior class of just about 100 kids, we knew each other.

“So I played from fourth grade in Missouri, we played with full pads, to the time I was a senior in high school and when I was a senior I only played for half the season because I hurt myself, so nine years total,” Chris said. “Even to this day, I still remember thinking this is so unnatural to run as fast as humanly possible and then hurl yourself into somebody.”

Chris never worried about anything but a hurt back in the 19 years since his high school football career ended.

'I knew something was wrong'

But in the last year, the husband and father started to forget things.

“Things that were big significant events, things that I have no recollection of. I think for me it was also really strange because I went to a small school right? And I come back sometimes and people I should know...I honestly can’t remember their name,” Chris explained.

His wife, Jerae, says she's also noticed mood swings.

“I don’t know he’s just…He’s really really chill until he’s just kind of not and it’s just, it’s very short,” Jerae said.

The search for answers

And then, Chris found a study out of Boston University that talked about high school athletes and concussions. People who had only played high school football donated their brains to the university’s brain bank. The study found three out of 14 had chronic traumatic encephalopathy, also known as CTE.

“I remember blacking out on occasion, hitting the turf or hitting somebody and blacking out. And those times when I passed out nobody really knew because you just fell and then it was only for a split second and then you pop right back up and then go do another play,” Chris said.

Researchers are still trying to understand CTE: what causes it, how to prevent it and even how to diagnose it.

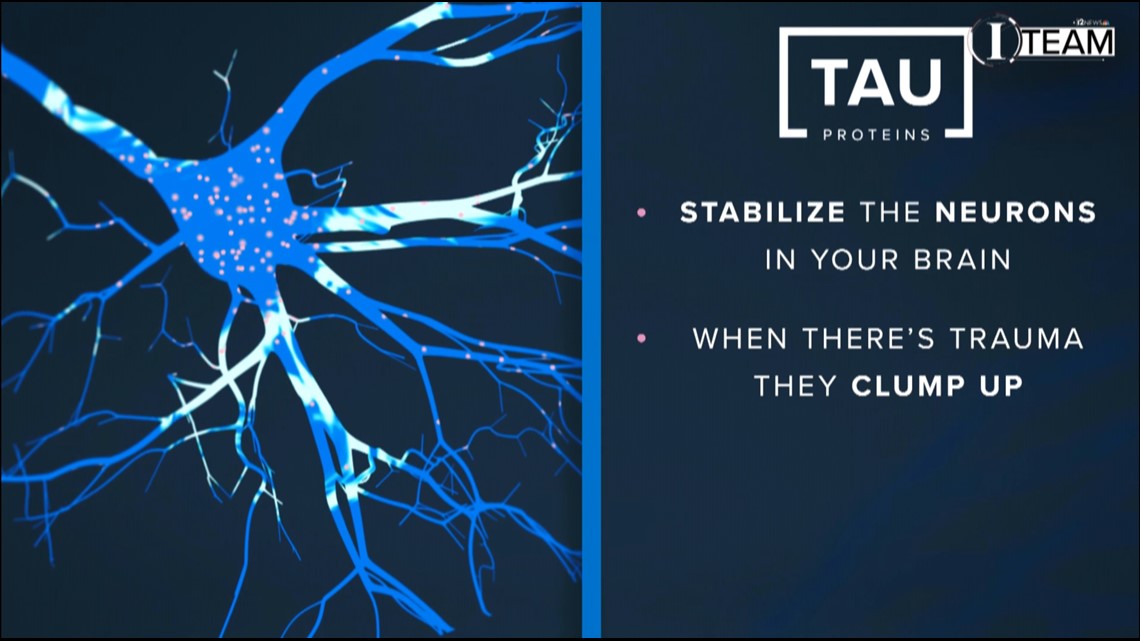

Researchers say it has something to do with proteins in the brain called Tau proteins. Those proteins usually help stabilize the neutrons in your brain. But when there’s trauma to the brain they break off the neurons and clump up.

Dr. Charles Adler is one of the leading researchers of CTE and other degenerative brain disorders.

He says while Tau is present in CTE cases it’s probably not the only factor. And while they believe concussions cause CTE they don’t know why one player may have CTE and another won't.

“Does every player who’s playing NFL football or play professional rugby develop CTE? I think the answer is ‘no’. Is there a higher risk of developing CTE with head impact sports? Probably ‘yes’, but we don’t have those numbers,” Dr. Adler said. “We know there’s an increased risk. At this point, I don’t think anybody can tell you what the percentage chance of an individual person is to develop a disease. The more head impacts or repetitive head impacts or injuries the more likely somebody is to develop CTE.”

The price to play

Former ASU linebacker Brandon Magee played football in high school. It was his ticket to college and then the NFL. And now, it’s his ticket to Hollywood. Magee is living in LA pursuing an acting career.

What ended his football career wasn’t concussions but other injuries.

“Who knows how I’m going to be down the road and that’s the scary part, but when I am playing you can’t look at it like that. I pray after every game, just blessed to be out there with my team,” Magee said in a 2012 interview.

Fast forward seven years and those injuries took a toll.

“I had to stop playing because I had a lot of injuries. And when I stopped my brain was going crazy because all of a sudden I had no schedule, no team, no contracts, big money wasn’t rolling in and I was like what am I going to do? And luckily, I had people to turn to and the artwork. It’s my form of expression. I don’t even let people know I paint. It’s just something I like to do for me,” Magee said.

He says art has helped him deal with the mental struggles of not being a professional athlete anymore.

“Because we’re not conditioned or taught to think about the life after the game. So, it is very hard, very hard. Because you have to reinvent yourself,” Magee said.

'I was just scared'

It took two years for Magee to recover from those injuries and the mental stress of being famous and suddenly being a normal person again. And that was when he started to think about those injuries and those concussions.

Magee recalled having six documented concussions during his time in college and playing professionally.

And when a huge group of players sued the NFL over concussions the settlement with the league called for every player to have access to a brain scan. Magee signed himself up.

“And I missed the flight on purpose because I got too scared. I didn’t want to know if I had anything or if anything was wrong with me. Because I felt like I was so young and if I found out there was something wrong that it would really affect me,” Magee said.

There's no test for CTE

Magee said his scan came back clean.

But no scan can detect CTE. Adler and a team of researchers at the Mayo Clinic and Boston University are working on it.

“So at this point, you have to do an autopsy on the brain to diagnose CTE. By then, we obviously can’t treat the patients so the goal would be first and foremost to make the diagnosis while someone’s living,” Adler said.

They have been able to tag the Tau protein in a patient’s brain with an isotope that can be picked up on a PET scan. They’ve been able to see the Tau in a limited number of former players. However, because the only way to diagnose CTE is to physically examine a person’s brain they won’t know if they’ve succeeded in creating a test until the players start to die.

“The ultimate goal would be to make a diagnosis of CTE prior to any clinical symptoms, so no mood problems, no behavioral problems, no cognitive problems, and then start some sort of treatment that would prevent that Tau from accumulating and hopefully prevent the disease from progressing to symptoms,” Adler said.

If we knew then what we know now

Magee said he doesn't think he would take any of his experiences playing back.

“And I think it’s because again we know what we signed up for and it’s about battle, it builds character, strength, overcoming obstacles, it sets you up for life even after the game,” Magee said.

Chris Wilson is left in a strange position. He doesn’t regret playing but he wishes he knew more back then.

“I would say if I had to choose between playing football and not playing football with the things I know now because when you know better you do better, I don’t think I would’ve played. However, I do think it taught me a lot of great stuff that set me up for a lot of life lessons,” Chris said.

“So regardless, I’m gonna live my life and whatever happens down the road happens, and looking back my legacy will be left here and hopefully people follow the journey, learn from the journey and whatever happens happens,” Magee said.

There’s no cure for CTE, and so far, nothing researchers have tied has worked. Dr. Adler is working on a much larger study on concussion patients, but it does not involve high school athletes.

Adler says maybe one day they’ll be able to diagnose CTE and hopefully prevent it. But that day seems like a long way off.