My first day as a TV reporter was on 9/11. Now I’m covering its 20th anniversary

Every one of us has our own connection to 9/11, and we each remember the day in a different way.

I recently interviewed the parishioner, the pastor and the photographer -- three people who I met on the morning of September 11, 2001.

The interviews felt like mini-reunions; somber, but somewhat joyful, as we recalled a chilling and disorienting morning for all of us and what has happened to our country in the two decades since.

Fresh out of college

Every one of us has our own connection to 9/11, and we each remember the day in a different way.

For me, the first thing I remember is the realization that our country was under attack.

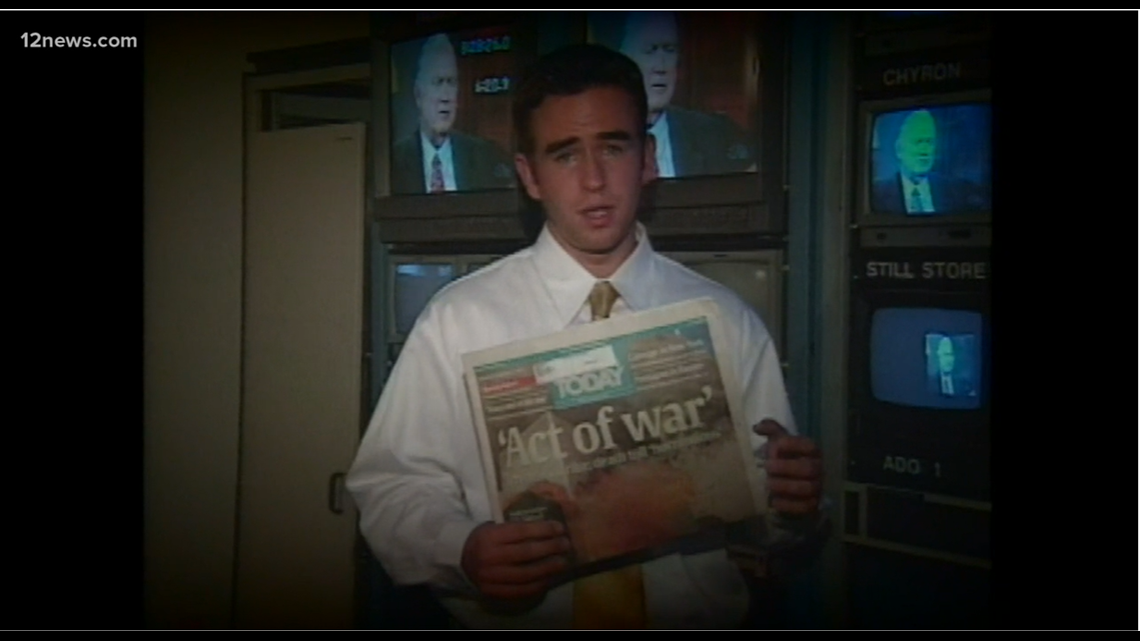

But I also think about the way covering the attacks changed my life professionally as September 11, 2001, was my very first day working as a professional journalist.

I had just arrived in Flagstaff that Sunday from my college town of Provo, Utah. I would begin working at a small TV station, 2 News, serving communities in northern Arizona.

On Monday, Sept.10th, I had lunch with my news director where we discussed how I would officially begin my job on Tuesday morning at 4:30 a.m.

We discussed our mutual passion for World War II history and the bomber planes used during the war.

I told him about my great-uncle who died piloting a B-24 Liberator. War heroes, foreign enemies, U.S. casualties, that was all stuff of history books to me.

Little did I realize our country was mere hours away from an attack akin to Pearl Harbor. Two wars would follow. Eventually, my great-uncle would cease to be the closest person in my life who died for his country.

The attack

Early the next morning I watched with intensity and horror at the TV news coverage like so many Americans. The anchor who was training me furiously typed scripts in preparation for the local 6:30 a.m. newscast.

We wouldn’t need them. The national coverage trumped our local coverage on that morning given the gravity of the events unfolding.

Within hours, our small staff huddled to decide how we would cover the collapse of the Twin Towers in a big city far removed from the mountain community of Flagstaff.

The attack felt both intimate and distant. My photographer and I went to a church to speak with fellow Americans.

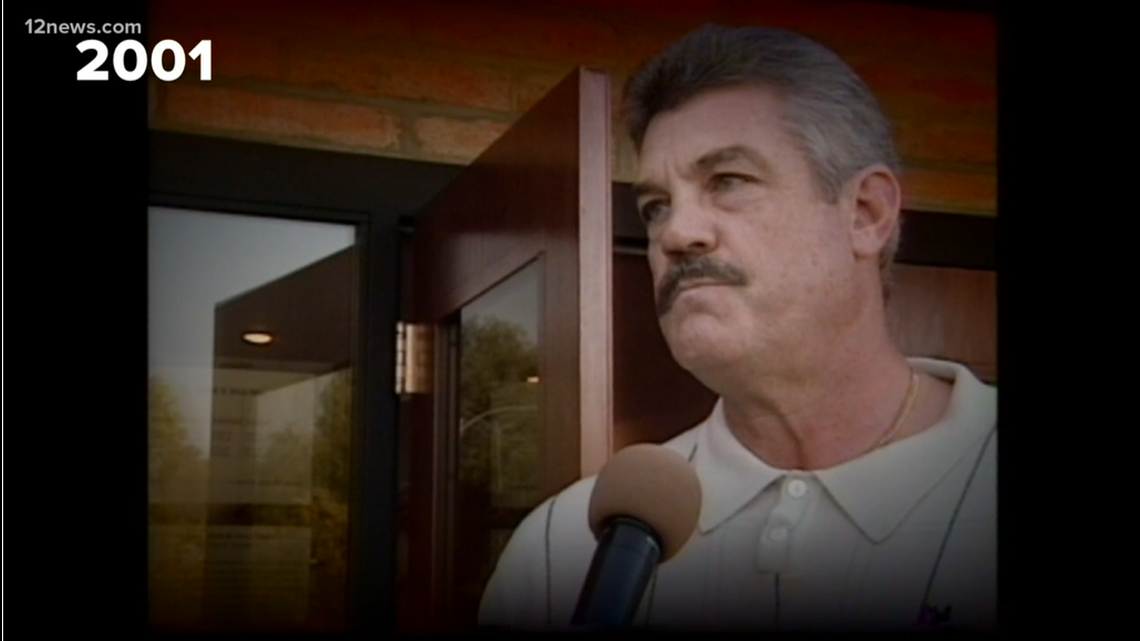

The parishioner

That’s where I met Steve Jackson, a Flagstaff real estate broker. Jackson had just sent home his employees and was trying to grapple with a mashup of shock, fear, and anger.

“One part of you wants to go over and annihilate. The other part of you wants to make sure the right people are held accountable,” Jackson told me then.

A comment from another parishioner struck me as a representation of the chaos and confusion of that morning.

“I don’t know who to pray for most at a time like this,” he said with his voice trembling.

On a recent afternoon in Flagstaff, I reconnected with Jackson. I asked him if he was satisfied justice was done. He replied, "yes.'

“I think when they took Osama Bin Laden out, it was a big celebration for the country,” Jackson told me. “For many years there, it was like the country was salivating, hoping to find him.”

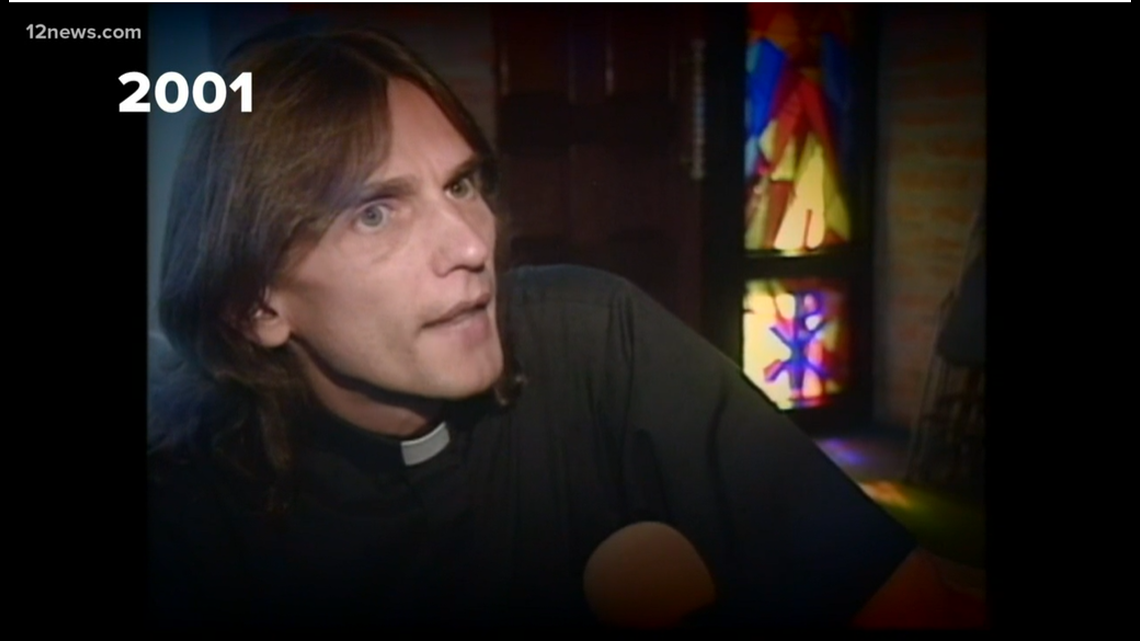

The pastor

Father Gary Regula was the associate pastor at St. Pius Church in Flagstaff in 2001. That morning, he held an impromptu church service for Jackson and a couple of dozen parishioners.

When I interviewed Regula the first time, he acknowledged there would be a clamoring for revenge.

“There will be anger, there will be hate. That’s part of it. But they can’t let that control them,” Regula said 20 years ago.

Regula’s warning would be prophetic. Many Americans would commit hate crimes against Muslims or people perceived to be Muslim, including the murder of a Sikh-American businesses owner in Mesa just four days later.

'It was a time I needed to learn'

I reunited with Father Regula at Saint Jerome Catholic Church in west Phoenix where Regula now leads a congregation.

I asked Regula how he felt our country was doing on the issue of hate after 20 years.

“There are sadly some extremists and then we sometimes still label them as a whole community,” Regula said. “We have to come back in a sense to a deeper connection with of our faith, which is to love, love one another. And it’s hard. It’s not an easy road.”

Regula added that since 9/11, he has personally met with Muslim leaders to discuss what they have in common.

“I would say it was a time I needed to learn,” Regula said. “I realized there is more written in the Quran about Mary, who we say is the mother of God, than is written in the Gospels.”

The photographer

Mark Sparks was one of three photographers for 2 News who captured video for us on that historic day.

The vigils and comments he recorded portray a mountain community banning together with lawn vigils, speeches and a candlelight ceremony.

“It was about people trying to comfort each other. And eventually, it was about people protesting the war,” Sparks said to me recently as we discussed the months and years that followed 9/11.

Flagstaff is situated near a military armory, and there were questions that day about how quickly soldiers might be deployed.

“If you would have told me then, that we were about to enter a war that would last 20 years, I probably would believe it,” Sparks said.

As for me, I never could have imagined 20 years later, I would be covering the end of the war in Afghanistan.

Covering soldiers and casualties

Over the last two decades, I covered soldiers getting deployed and soldiers dying.

The reality of the war hit me over and over again, and I never got used to it.

What was especially heartbreaking was the 2004 death of Army Sgt. Elijah Wong, the son of a Jewish-Israeli father and Chinese mother. Wong, a father of three children, represented the diversity of the country that he served.

“We may not always believe in the powers that be in this country, but we believe in the United States,” Wong’s sister told me after his death. Her words brought me a degree of comfort during a time she was the one needing support.

In 2007, I covered Sgt. 1st Class Brian Mancini, a medic injured by a roadside bomb in Baghdad. I interviewed Mancini several times for stories about alternative therapies for service members suffering from PTSD.

In 2017 he experienced a rapid decline in his own mental health and sadly, ended his life.

His rescue mission continues through the legacy of the nonprofit he founded, The Honor House.

Losing my friend

The Iraq war became personal after my childhood friend, Radu Micula, took his own life.

Radu returned from a tour in Iraq in 2004 and suffered mental anguish that he could not resolve. He was innocent and loving to everyone he knew and I couldn’t help but think human beings, especially Radu, are not built to experience war.

After Radu’s death, I made it a priority to cover the epidemic of veteran suicides in the U.S.

Lessons from 9/11

That morning dramatically influenced issues I would cover for the next two decades.

Terrorism, homeland security, war, airline travel, multiculturalism, mental health; the list goes on.

Since that day I have learned not to take for granted journalists’ role as a watchdog in the community, and not to take lightly the privilege we have to cover the government and powerful figures in a free society.

The best way I can honor the lives of those lost on 9/11 and in the two subsequent wars is to perform my role with professionalism and an eye towards public accountability.

Up to Speed

Catch up on the latest news and stories on the 12 News YouTube channel. Subscribe today.