PHOENIX — It is not that Boxer 6 never existed. It was its violent disappearance that caused generations of heartache.

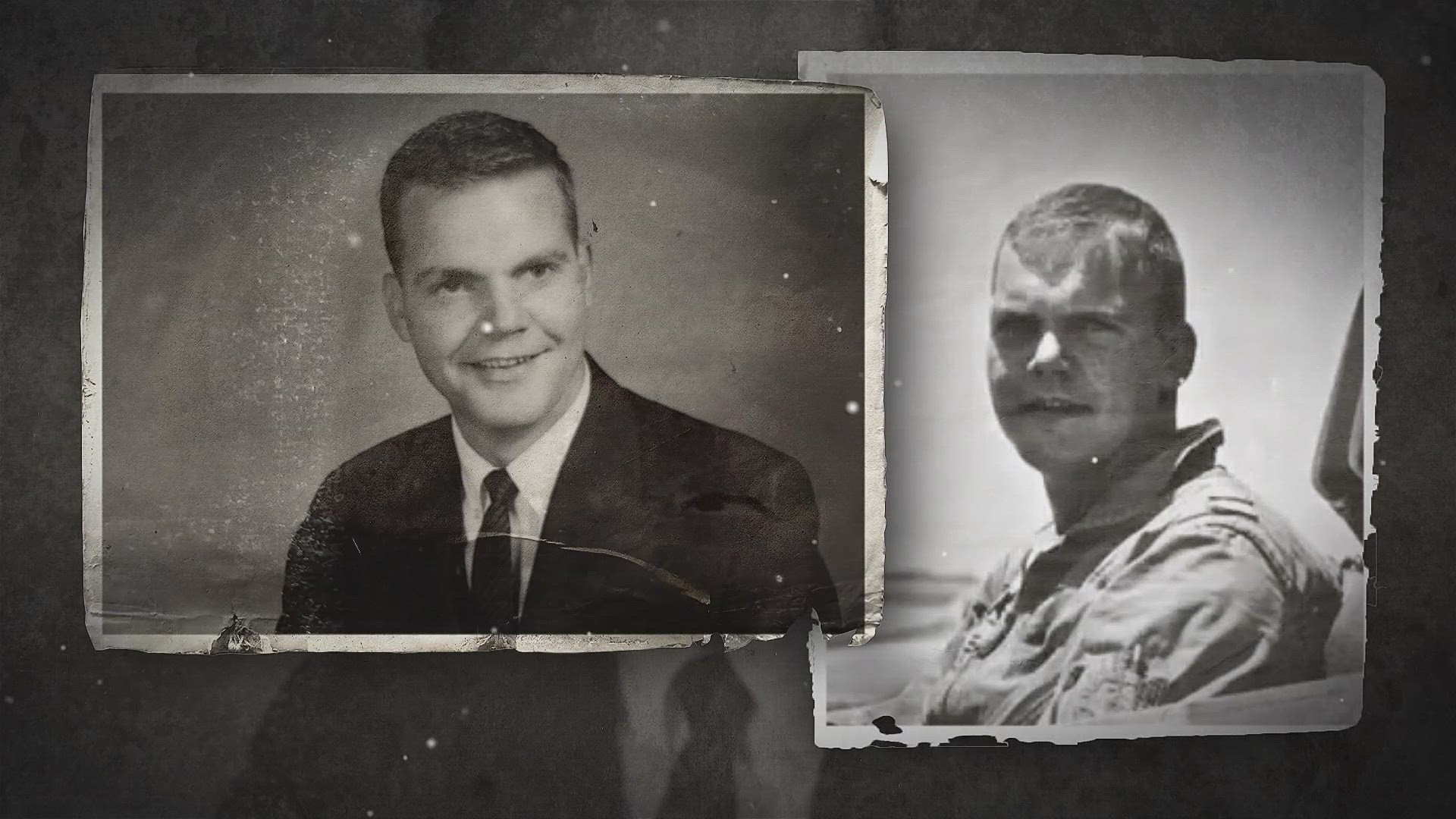

"Boxer 6" was the call sign for Capt. Charles Walling's F-4C Phantom fighter plane that took off, loud and smoky, from the U.S. base at Cam Rahn Bay on August 8, 1966. It was Walling's 45th mission, this one to bomb suspected Viet Cong troop concentrations about 40 miles northeast of Saigon.

After the fourth bombing run, the airborne controller managing Boxer 6's mission saw an explosion on the ground five miles away. Boxer 6 didn't answer radio calls. There were no parachutes. There were no signals from the search-and-rescue radio beepers that pilots were equipped with in case they crashed.

The controller and another Phantom flew over the area where the explosion occured. All they saw was an impenetrable jungle canopy in an area teeming with Viet Cong soldiers.

It was as if Walling and his radar-intercept officer, 1st Lieutenant Aado Kommendant, had ceased to exist.

But Walling, of Phoenix, left behind a wife who was six months pregnant and an 18-month-old son. And soon, they got word that he was missing in action.

Agonizing weeks turned into months. Eventually they started to accept that he had been killed in action.

In 1994, site investigators found some pilot gear and Walling's dog tags. But it wasn’t until December of 2011 when a special military unit tasked with finding the remains of Americans who were missing found his remains and flew them home. There wasn't much — some bone fragments, a belt buckle — but enough to postively identify Walling.

We were there at Arlington National Cemetery when Lt. Col Walling — he was posthumously promoted twice — was buried with full military honors.

Years would go by and Walling’s sons, Jeff and Michael (who he never met) went about their lives. And the one night late last year, Michael's phone rang.

Would he be interested in going to Vietnam to see the crash site and to meet with his Vietnamese counterparts?

These were the North Vietnamese offspring of soldiers who had been killed by Americans. It was part of something called the “2 Sides Project," a project meant to unite the children of those who had fought. The project was begun in 2015 by Margot Carlson Delogne, whose father, Air Force Capt. John Carlson, was killed in 1966.

"It was a opportunity that (his wife) Dina and I never in our wildest and my brother Jeff, never in our wildest dreams thought we'd have," Mike Walling said. "So to have an opportunity to go and be where my father's crash site. And even more important to me were his final moments and experience that really brought a connection that in our wildest dreams, we never thought we'd ever have."

Nearly 60 years after their father's death, it was a chance for the Walling boys to find closure. And for Michael's wife to find a kind of closure, too.

"My heart was exploding," Dina Walling said. "I was so happy for them. And myself, because I've lived most of my lilfe with this. He could have been my dad, too."

The Wallings went to Vietnam, with two other American couples that had lost parents in the war. Jeff, Charles Walling's older son, was diagnosed with cancer two weeks before the trip. But through the miracle of Facetime, every time Mike and Dina visited a site, Jeff was able to be there with them.

They visited Cam Ranh Bay, where Charles Walling was stationed with the 557th Tactical Fighter Squadron.

"Dad, to you," Michael said, raising a glass to his father not far from where Boxer 6 left for its last flight. "So here's a nickel on the grass to you ... a dying breed ... When you are gone the world will be a lesser place."

"The visit to Cam Rahn Bay ... was incredibly important to us, because that's where he was stationed. That's where he lived," Mike told us later. "And he was on the beach, and it was beautiful. One thing that kept going through my mind 'I'm so fortunate, we are so fortunate that my father got to spend his last days, hours, minutes, in this amazing beach location before he hopped on his plane.'"

And then there was the crash site, which had been heavily defended by Viet Cong troops at the time of the crash. Mike had a private conversation with his father there.

"It was really just a way to say I love you, I'm sorry, we never got to meet,'" he told us. "Thank you for instilling in us the values that we are, even though that was related, and for giving us the courage to be here. And just everything in life nothing's comes easy, right?"

The trip didn't make their father’s death any easier. It wouldn’t make up for the missed birthdays and Christmas mornings.

What did was looking in the eyes of the equally wounded Vietnamese who had gone through the same thing. The next generation that had felt that pain and anger that the U.S had taken their father, uncle or brother. Another group of adults that had lived a life with that empty pit in their stomach, that war had also cheated them.

"I think we're I had the most relief with my anger was when we were meeting with the sons and daughters of the Vietnamese killed in action. And hearing them say the same things I felt, which were, all I wanted to ever do was hug my father and say, 'dada,' you know, or things like that. And knowing that they had almost those exact same emotions. And through that realization, anger and hurt gave way to acceptance, healing and understanding."

Up to Speed

Catch up on the latest news and stories on the 12News YouTube channel. Subscribe today.