LOS ANGELES — After almost three years of work, a team of conservators at the J. Paul Getty Museum have successfully restored and repaired a painting that was violently stolen in 1985 and are preparing it to return to public display this month for the first time in 37 years.

“When it first came to the Getty all you saw was the horrific damage that was done to the painting – which was very violent, said Ulrich Birkmaier, the senior conservator of paintings at The Getty. “Now it has come back to life. It’s a resurrection really. It’s very satisfying to be able to bring it back.”

The Getty, located in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles, is not only a world-class art museum but it’s also a bit of an art hospital.

“Yes, you could say that actually,” Birkmaier told WFAA. “Incidentally, we use some of the same tools that surgeons might use – or dentists.”

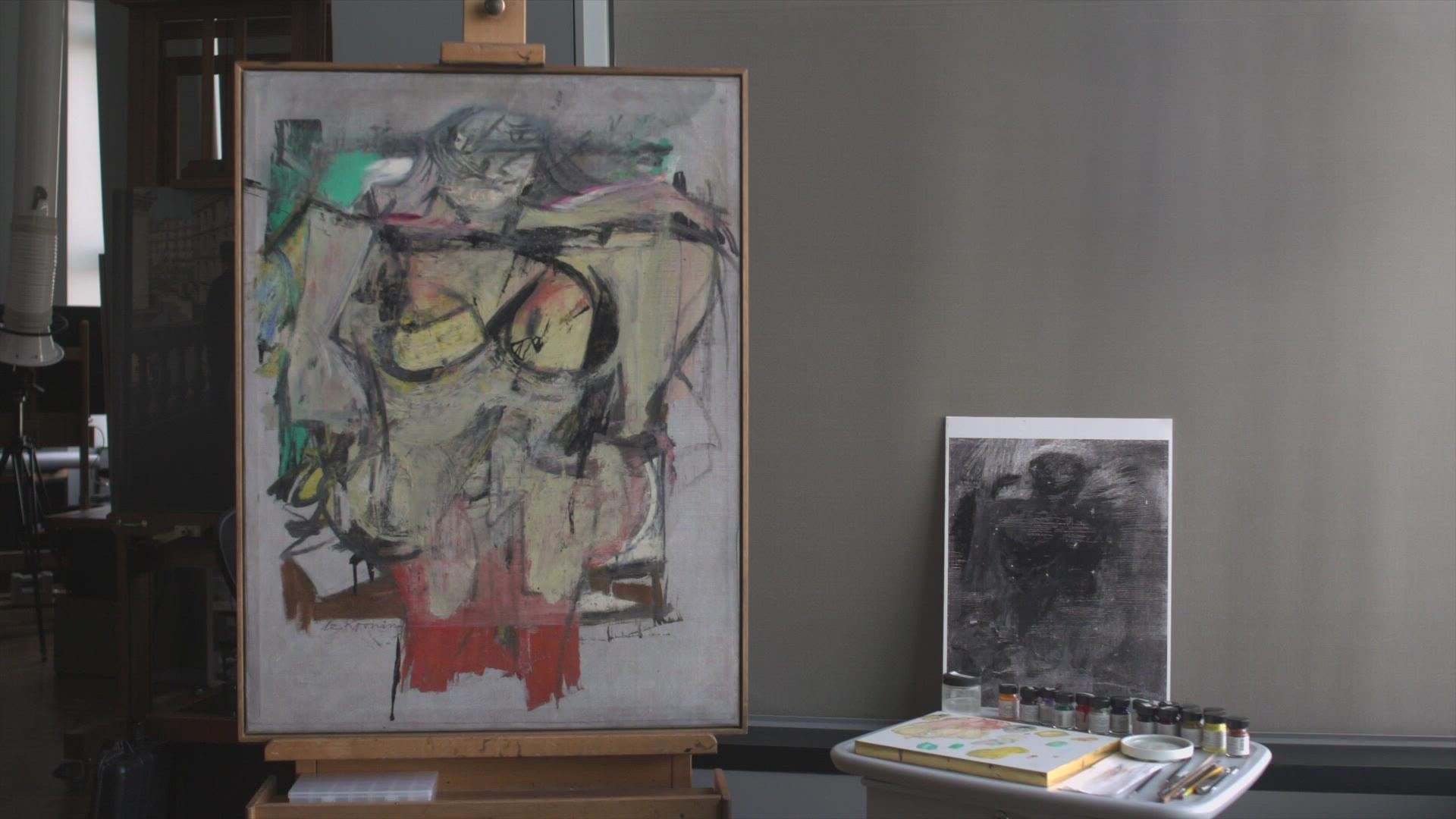

For three years, he has led a team working patiently to salvage an expensive painting called Woman Ochre. The Dutch-American artist Willem de Kooning painted it in 1954-1955. It remains among the finest examples of abstract expressionism in American history.

“The sheer amount of damage at first sight seemed kind of overwhelming,” Birkmaier recalled to WFAA at the lab in southern California.

In a 2018 documentary, WFAA detailed the savage theft and laid out for the first time why two married schoolteachers in rural New Mexico are suspected of stealing the painting.

“I was just cleaning up details and this changed everything,” said Ron Roseman, a former Dallas resident, who is Rita Alter’s nephew.

She and her husband Jerry Alter appointed Roseman as executor of their will. In 2017, after Rita died, and five years after Jerry died, Roseman was almost finished liquidating their estate when the FBI called.

“They were inquiring about a painting that was found in my aunt’s house,” Roseman recalled in the WFAA documentary.

The Alters home in Cliff, NM was full of art. But the FBI agent wanted to know where his aunt Rita got one specific painting that she kept hidden behind her bedroom door in a cheap gold frame.

The FBI said the painting was Woman Ochre and had been stolen the day after Thanksgiving in 1985 from the University of Arizona’s prestigious art museum.

The thieves cut the canvas out of the frame, rolled it up – cracking the oil paint and damaging it even more – then fled.

“Thirty-two years ago, this painting was valued at $400,000. Now we’re talking $150 million dollars,” said University of Arizona Police Chief Brian Seastone in a 2018 interview with WFAA.

Investigators said the thieves were a man and woman but might have been in disguise.

“I can’t imagine that they would [be involved]. That wasn’t the aunt and uncle I knew,” Roseman said.

But circumstantial evidence began to mount.

Turns out, Jerry and Rita were big fans of Willem de Kooning.

WFAA can place the Alters in Tucson, Ariz., – near the art museum – the night before the theft. Ron Roseman has a photograph of himself with the Alters and other relatives at Thanksgiving dinner about 12 hours before the crime.

Plus, Jerry and Rita owned a red sports car, like witnesses said sped away from the museum after the crime. And perhaps the most critical piece of evidence, the stolen painting, was found behind their bedroom door after they died.

“As an investigator, an art crime investigator, I’m 96-98% sure they were involved,” said Bob Wittman, a retired FBI agent in Philadelphia who launched and led the FBI’s national art crimes team.

And Wittman said he thinks that the Alters might have been involved in more thefts.

“There are cases where individuals do a shoplifting and they will steal one item. But in the case of the Alters, because of the way did it and they had the courage to go in there and do it, I wouldn’t think that’s the only thing they ever took,” he continued.

Still, no other stolen items have ever been linked to Jerry or Rita Alter.

Even if they did not steal de Kooning’s Woman Ochre, they knew what they had and kept it hidden behind their bedroom door for years.

Several years after the Alters’ death, the FBI said the theft of Woman Ochre remains an open case.

“I would never hazard to dispute what the FBI says but I can tell you I very much doubt there’s any active agents right now working on leads involving this case,” Wittman explained.

When pressed on what it might take for the FBI to finally close the case after 37 years, Wittman added: “Closing it is basically a memo to the file saying there’s no further investigation needed. So, at this point since they haven’t got a suspect, a squad supervisor will say, ‘why don’t you close the case?’”

Plus, Wittman said, if the case was still open, the painting would be held for evidence by law enforcement, not sent to The Getty in 2018 to be restored.

“The thieves probably rolled the painting up, most likely face in. And put it under his coat [to escape],” Birkmaier said.

It makes him cringe to think about the damage done during the theft.

Paint began flaking off immediately, and deep lines of missing colors emerged across the canvas.

But Birkmaier said his team at The Getty discovered something else while restoring it – something the thieves did to the painting.

“They addressed some of the damages that had occurred as a result of their violently pulling the painting off that frame,” he said.

In other words, they tried to touch it up and repair the damage they inflicted.

“They actually put a big patch of canvas to the reverse of the canvas to support areas of tears,” Birkmaier explained. “They filled these tears and tried to paint them in, retouch them a little bit.”

Laura Rivers, an associate paintings conservator at The Getty, had the $160 million dollar painting under a microscope for a year and a half.

“So, as I was sort of setting down the paint in those areas where the damage is still visible and very clear, I was also still gathering the small fragments nearby in order to sort of clarify the image,” she said.

Rivers collected countless flecks of original paint, almost invisible without a microscope, that will never go back on the canvas, she said, but instead they will be saved to be studied.

So, after three years of meticulous restoration at The Getty, the original damage is now difficult to see from just a few feet away.

The cut canvas was reaffixed to a new stretcher and the deep lines of broken paint have been carefully blurred out.

“I have learned in this field that many miracles can happen,” Rivers told WFAA at The Getty. “I think we’ve been able to take this painting further than I initially expected. It is a pretty catastrophically damaged painting.”

This month, Woman Ochre goes on public display for the first time in 37 years.

It’s at The Getty from June 7 to August 22. Afterwards, the painting will be returned to the University of Arizona.

The Getty spent “many hundreds of hours” restoring the painting, Birkmaier said.

He still has a little work left to do before Woman Ochre goes into a gallery next month. Birkmaier is still filling in missing paint with a small tool and applying one dot at a time.

“Some elements of the conservation process are a little bit like plastic surgery, insofar as the best work is one you don’t really know,” he added.

Still, some scars remain and always will.

But what happened to Woman Ochre – the theft, the damage and the restoration – are now part of this painting’s provenance. It is a fine piece of American abstract art with a story now as rich as the work itself.