LA PAZ COUNTY, Ariz. — Bill Farr doesn't need to wonder when the water in his well will get low.

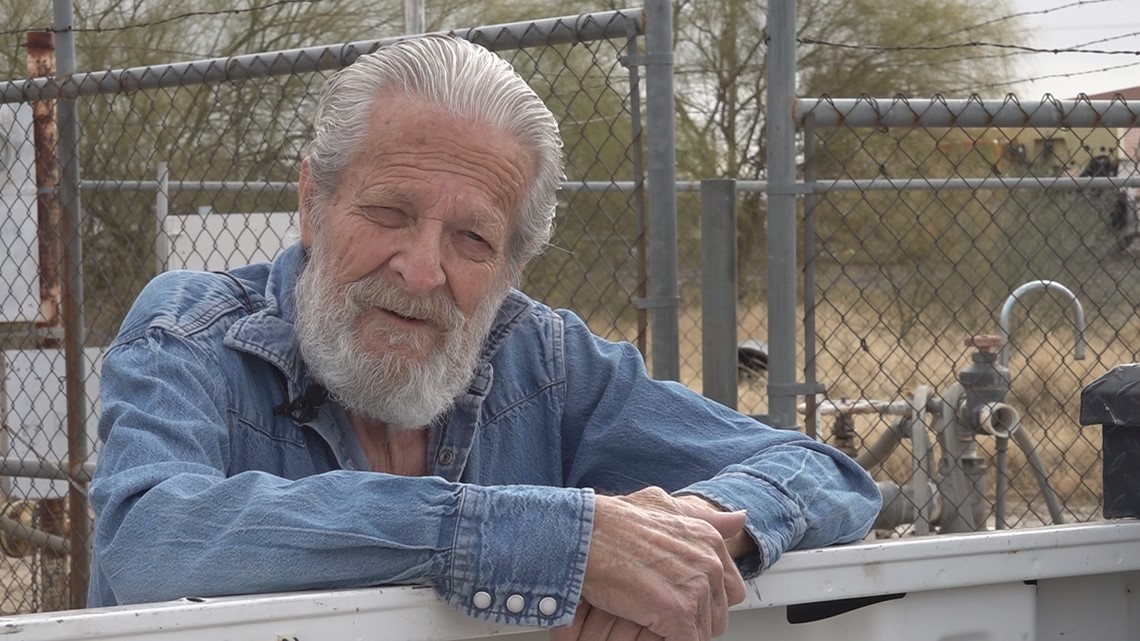

"I'm there now," he said, leaning on his truck, parked near the well. It's a mass of pipes and valves behind a chain-link fence, all leading to a big pipe that disappears into the ground.

Farr is 74 years old, with a face that shows a lifetime spent outside in the Arizona desert.

He has owned Salome Water Company for 50 years. It was easier back then, he says.

The well was dug down to 700 feet. Water used to be only about 300 feet down. Now, the water is at 600 feet. More years of this and his pump won't touch the water at all. That's why he's not taking on any new customers. He's stopped at about 100. Not that the town of Salome is much bigger than that.

"Gotta take care of the people that have water meters and have been established," he said.

There's a water tower about 100 yards from the well. Farr can tell from looking at it that it's almost full. But he says there are days he can't provide enough water for everyone who needs it.

There are two reasons for that, Farr says. There's the 22-year-long megadrought that Arizona is dealing with. And his neighbors down the road: huge commercial farms owned by Saudi Arabian companies that use all the groundwater they could ever need.

The largest is owned by a company called Fondomonte. It's a subsidiary of Almarai, which is one of the largest dairy suppliers in the Middle East.

Fondomonte and Almarai grow alfalfa in Arizona, cut it, bale it, and truck it to port. Then it's shipped back to Saudi Arabia to feed Almarai's dairy cows.

Almarai does this at farms in various locations around the world. Spending money to bring food from halfway around the world to its cows. The company does this for a very specific reason; growing alfalfa is illegal in Saudi Arabia.

It uses too much water.

Now Arizona's attorney general wants Fondomonte to pay for it.

The lease

Alfalfa is a very water-intensive crop.

Experts say it's not that it requires a lot of water to grow it in the first place; it's because alfalfa never stops growing. Farmers who grow it can cut the fields many times a year, and it grows back. Most farms grow fields of alfalfa at different times so that they're always harvesting.

In 2018, Saudi Arabia finalized a ban that made sure the kingdom's farmers would not be able to grow alfalfa. Agriculture uses more water than residential customers do, and water-intensive crops were straining Saudi Arabia's water supply.

Now, Saudi Arabia depends on overseas farms for livestock feed like alfalfa and hay.

And in Arizona, Fondomonte found the perfect place to grow alfalfa: La Paz County.

It leased just under 10,000 acres from the Arizona State Land Department near the town of Vicksburg.

But the lease is for half the market rate, only $25 an acre. The entire farm was leased for under $100,000 a year.

Even better, the state would let Fondomonte use all the groundwater the company could pump free of charge.

But experts say Fondomonte was just doing what companies do; finding the best business scenario.

"It seems that a lot of the conversations about the Saudi farm deals in Arizona are really missing the point," Natalie Koch, a professor of geography at Syracuse University, said.

"What are they taking advantage of?" she said, "They're taking advantage of Arizona's really lax water laws."

The consequences

"I started getting complaints from residents about their wells running dry," La Paz County Supervisor Holly Irwin said.

Irwin said the more straw Fondomonte stuck in the ground to take groundwater, the more stress was placed on the aquifer in the Butler Valley.

And groundwater doesn't get replenished with a heavy rainstorm. Groundwater can be hundreds or thousands of years old and is generally not thought of as renewable.

"There is absolutely no restrictions that were put on any of these wells," Irwin said.

Most of Arizona's rural groundwater is unregulated, experts said. Even while the state is in a megadrought that is slowly (but not that slowly) draining the reservoirs that supply the West with water.

Heavy cuts to Colorado River water have already hit agricultural users in the state. Some farmers have been cut off from Colorado River water completely. They have to rely on well water if they have a well in the first place

But Butler Valley doesn't use Colorado River water. There are no canals to bring it. It's entirely run on groundwater.

"Now we have all these different companies coming in and depleting our natural resources, and that's an issue," Irwin said. "And that's something the state, at some point, is going to have to address."

The challenge

Newly elected Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes ran on the promise of challenging the state's lease agreement with Fondomonte.

Now that she's elected, she said she wants to repeal the agreements within six months.

"I have never seen anything this egregious by state government in my life," Mayes said.

Mayes believes those leases constitute an illegal gift under the state constitution. And she wants back pay for the water Fondomonte has used: $38 million.

"Every single day counts," Mayes said. "That water is coming out of the ground every single day."

“Arizonans are right to be outraged that the State of Arizona would allow a Saudi-owned corporation to stick a straw in the ground and suck the water out for free," she said.

"It's completely unfair," Holly Irwin said. "It's criminal in my opinion."

Bill Farr doesn't know what the future holds. His water company doesn't make him rich. He doesn't take a salary anymore. He has received an offer to buy the company, but says he won't take it.

"I don't know what I'm gonna do, to be truthful," he said. "To be truthful, I'm just tired."